Tuning and Stringing the Dilruba or Esraj

| STRINGING AND TUNING THE DILRUBA AND ESRAJ Section 1 – Introduction Section 2 – Basic Concepts of Tuning Section 3 – Overview of Strings Section 4 – Dilruba/Esraj Strings Section 5 – Tools Section 6 – Stringing the Base Section 7 – Stringing the Tuning Pegs Section 8 – Tightening the Strings |

This page will discuss the philosophic and conceptual issues involved in tuning the dilruba, esraj, and tar-shehanai. It is impossible to consider the topic of tuning until one has a clear idea as to what you want the instrument to do, and what you want it to sound like. When you put a string on your instrument, the string does not know, or care, what it is. A particular string does not have any way of knowing whether it is Sa, Pa, Ma, or what. The string does not possess music. The string does not have any aesthetic quality. Just like the painter has to decide if a particular shade of green is reminiscent of grass; the musician must decide if a particular string is best suited for a particular musical purpose.

One would think that this should be a trivial task; but it is not. The nature of Indian music is such that these concepts will change from one piece to another. Furthermore, there will inevitably be differences in artistic vision; such differences may arise from the genre that the instrument may be used in (e.g. shabad, film songs, gazal). Differences may also stem from practical concerns such as whether one will be using the dilruba or esraj for solo or in accompaniment situations. For whatever reasons, there will never be a “standard tuning”.

Although there will never be a standard tuning, there are only a few standard approaches. Therefore, if we turn our attention to approach rather than an actual tuning, our job becomes easier. Actually we are not even dealing with a single issue but a series of interdependent approaches. We may generally say that the issues deal with the nature of intervals, the number and function of the strings, and basic concepts of key. Furthermore, each of these topics must be considered against the unforgiving benchmark of what is practical and what is not.

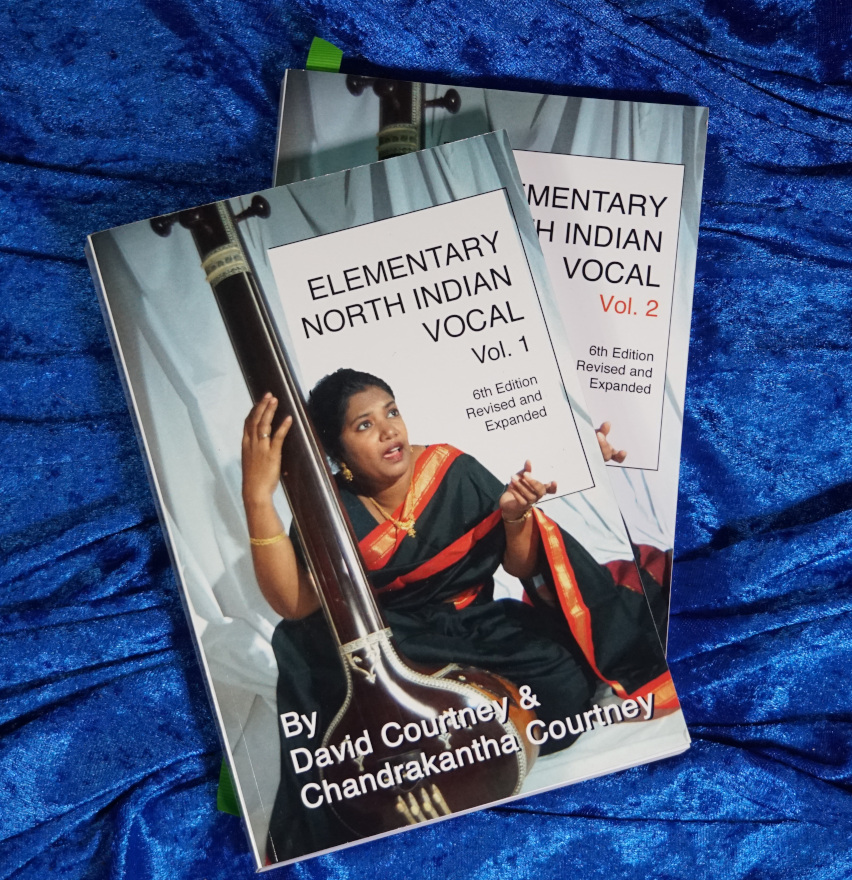

| THESE BOOKS MAY NOT BE FOR YOU |

|---|

A superficial exposure to music is acceptable to most people; but there is an elite for whom this is not enough. If you have attained certain social and intellectual level, Elementary North Indian Vocal (Vol 1-2) may be for you. This has compositions, theory, history, and other topics. All exercises and compositions have audio material which may be streamed over the internet for free. Are you really ready to step up to the next level? Check your local Amazon. |

Function of The Strings

The dilruba and esraj generally have two classes of strings; each of which is further divided into two groups. Here is a brief description.

At the highest level, there are the main strings and there are the sympathetic strings. The main strings are defined by their ability to be bowed. They are located above the frets of the dilruba. The sympathetic strings are located below the frets. These cannot be bowed, but they contribute to the overall sound of the instrument. These are both illustrated in the picture below:

The sympathetic strings are the ones which cannot be bowed. In the dilruba, they are located below the frets. In the esraj they are above the frets, but run diagonally in a fashion that resists bowing. They function as a sort of non-electric reverb unit. They produce the effect by vibrating whenever the appropriate note is bowed on the main strings. There are two classes of sympathetic strings; there are the ordinary sympathetics (a.k.a taraf, or tarafdar) and then there are the jawari strings. The difference between them is to be seen in the small flat bridge that is located on the upper part of the neck. This bridge is called the jawari. It may appear to be flat at first, but upon closer examination, you will see that it has a gentle curve. It is this contour which causes the bridge to slightly buzz, and thus acquire a slightly different sound. There is no standard as to how many jawari bridges will be on your instrument. Sometimes there is one, sometimes there are two, and sometimes there are none at all. The ordinary sympathetic strings (tarafdar) do not have the jawari, and consequently, do not have the same piercing sound. The purpose of the jawari strings is to emphasise particular notes.

The main strings are also divided into two classes; there are the playing strings and there are the drone strings. However unlike the sympathetic strings, the distinction between the playing strings and drone strings is far less clear. We are certain that the first string is definitely the main playing string and the last string (string 4) is almost always a drone string. However, the function of the second and third strings are at times a bit vague. The bottom line is that when we play and fret the strings they become playing strings and when we don’t fret them, they become drone strings. I know this is very circular, and such circularity is a stamp of intellectual carelessness, however it does underscore one important point. Strings two, three, and four, can be whatever you want them to be.

The Intervals

The most important consideration in our tuning, is what the musical intervals between the strings are going to be. In Indian terms, we have to first decide whether we are going to tune any string such that it is Sa, Re Ga, etc. It turns out that there are several common approaches. Let us look at them in greater detail.

![]() – In this tuning, the main playing string (string #1) will be tuned to Ma in the mandra saptak (lower octave). The second string will be set to Sa in the lower octave. The third string will be set to Pa, two octaves lower, and the last string (#4) will be set to the Middle Sa. This is the one that we followed in the “Quick Guides“.

– In this tuning, the main playing string (string #1) will be tuned to Ma in the mandra saptak (lower octave). The second string will be set to Sa in the lower octave. The third string will be set to Pa, two octaves lower, and the last string (#4) will be set to the Middle Sa. This is the one that we followed in the “Quick Guides“.

All things considered it seems to be a fairly balanced approach. It gives a broad usable range from (High Ga or Ma) all the way down to Pa two octaves lower. The range of the instrument is just slightly less than three octaves. Furthermore the drone is rich and balanced.

![]() – This is just a variant of the previous tuning. All the strings are tuned and treated in the same way as tuning # 1, except the third string is dropped down to Ma instead of the Pa. This tuning may be used whenever the rag does not permit the use of Pa. Common examples are Malkauns and Chandrakauns

– This is just a variant of the previous tuning. All the strings are tuned and treated in the same way as tuning # 1, except the third string is dropped down to Ma instead of the Pa. This tuning may be used whenever the rag does not permit the use of Pa. Common examples are Malkauns and Chandrakauns

![]() – This is a very common variant upon Tuning #1. The only difference here is that the last string #4 is set to Pa instead of Sa. This tuning seems to be motivated more by practical measures rather than musical philosophy. In order to tune the last drone strong to middle Sa, it takes an extremely thin gauge wire. Such gauges have not always been practical in the past. Tuning the string down to Pa below middle Sa still gives a good rich drone, but may be implemented with a heavier (and more available) gauge string.

– This is a very common variant upon Tuning #1. The only difference here is that the last string #4 is set to Pa instead of Sa. This tuning seems to be motivated more by practical measures rather than musical philosophy. In order to tune the last drone strong to middle Sa, it takes an extremely thin gauge wire. Such gauges have not always been practical in the past. Tuning the string down to Pa below middle Sa still gives a good rich drone, but may be implemented with a heavier (and more available) gauge string.

![]() – This is merely Tuning #3 for rags which do not permit the use of Pa.

– This is merely Tuning #3 for rags which do not permit the use of Pa.

![]() – This is a fairly common tuning. It is also very appropriate for beginners. When new students are trying to wrap their minds around concepts such as drone strings vs. playing strings, the last two strings of this tuning are clearly differentiated as being drone strings. Unfortunately, this tuning has the most limited range, since only the first two strings can produce the melody. The range of this tuning is just barely over 2 octaves!

– This is a fairly common tuning. It is also very appropriate for beginners. When new students are trying to wrap their minds around concepts such as drone strings vs. playing strings, the last two strings of this tuning are clearly differentiated as being drone strings. Unfortunately, this tuning has the most limited range, since only the first two strings can produce the melody. The range of this tuning is just barely over 2 octaves!

![]() – This is nothing more than Tuning #5 for rags which do not permit the Pa.

– This is nothing more than Tuning #5 for rags which do not permit the Pa.

![]() – This tuning has the distinction of having the greatest usable range of all the tunings. For this tuning, all of the strings may be played for the melody. The presence of the heavy gauge 4th string permits playing all the way down to Sa at two octaves below the middle Sa! There is only one drawback of this tuning. The presence of the heavy gauge 4th string, places the dilruba or esraj under considerable tension. If there is a defect in design or fabrication of the instrument, this could cause problems.

– This tuning has the distinction of having the greatest usable range of all the tunings. For this tuning, all of the strings may be played for the melody. The presence of the heavy gauge 4th string permits playing all the way down to Sa at two octaves below the middle Sa! There is only one drawback of this tuning. The presence of the heavy gauge 4th string, places the dilruba or esraj under considerable tension. If there is a defect in design or fabrication of the instrument, this could cause problems.

![]() – This is nothing more than tuning #7 that has the 4t string dropped from Pa to Ma. This is appropriate for rags which do not permit the Pa

– This is nothing more than tuning #7 that has the 4t string dropped from Pa to Ma. This is appropriate for rags which do not permit the Pa

| This book is available around the world |

|---|

Check your local Amazon. More Info.

|

Tuning the Sympathetic Strings

It is difficult to make any statement as to the tuning of the sympathetic strings. They are generally tuned differently for each piece. However, if we look at the jawaris and non-jawari (tarafdar) strings separately, some general considerations emerge.

Jawari – Jawari strings are almost always tuned to notes of the rag. This is fairly clear so we need not delve further into the matter.

Non-Jawari Sympathetics (Tarafdar) – The tuning the non-jawari strings (tarafdar) is not strait-forward. There are a myriad of technical, musical, and practical considerations which need to be considered.

One common approach is to tune also the non-jawari sympathetic strings to the notes of the rag. This often produces a tuning such as:

Lower octave: Pa Dha Ni Sa

Middle octave: Sa Re Ga ma Pa Dha Ni

Upper octave: Sa Re Ga Ma

This is an approach that is often used. On the positive side, this tuning produces the cleanest, clearest drone and resonance. There are of course several practical considerations for this approach. The first is that you will have to modify the gauges of your strings. The lower pitched strings will need to be heavier gauge while the higher pitched strings will need to be a lighter gauge. The biggest disadvantage of this approach is the inordinately long time required to tune the instrument. This approach is very nice in situations where the quality of the sound is paramount in importance, and the time available for tuning is unlimited (e.g. recording situations). Unfortunately, when you get in stage situations, you will just not have enough time to retune for each piece.

There is another approach which also tunes to the notes of the rag. It may go something like this:

Lower octave – Dha Ni

Middle Octave Sa, Sa, Re Ga Ga Ma Pa Pa Dha Ni Ni

Upper Octave Sa Sa

(please note that the decision as to which notes to double up on are up to you.)

From a musical standpoint this approach represents a wasted potential and would at first appear to be inferior to the previously mentioned approach. However, it has a number of practical advantages. One advantage is that this approach may be implemented by using the same gauge strings for all of the non-jawari sympathetics. This is advantageous, because the moment you start altering string gauges, you limit your future options should you decide to uses a different tuning.

This tuning also has the advantage that it requires slightly less time to retune between pieces. This is especially evident as you move back and forth between rags with both versions of a particular note (e.g., both komal and shuddha Ni in Khammaj). Unfortunately there is still the problem of taking too much time in retuning between pieces.

Considering the practical considerations, my favourite tuning is as follows:

Lower octave – Pa Ni

Middle octave Sa Re Re Ga Ga Ma M’a Pa Dha Dha Ni Ni

Upper octave – S

This tuning is essentially chromatic. On the negative side, the resonance of the instrument is not as clean as with the previous approaches. However on the positive side, it is the only tuning that I have seen that will let you play the dilruba or esraj in real world, stage situations. With this tuning, you can move the whole key of the main strings up or down a half step with no problem. You can switch the rag any number of times and you only need to address the issue of the two strings in the lower octave (and of course the jawari strings). The flexibility of this approach has amply been appreciated by sarangi players who frequently use a chromatic tuning of the sympathetic strings and refer to it as “Acchal That” (literally – “the immovable mode”).

All things considered, it seems that practical considerations are so overwhelming in ones decisions on tuning the non-jawari sympathetic strings, that the available time usually takes precedent over purely musical considerations in determining exactly how these strings will be tuned.

Key

The key of the instrument is a very important consideration when determining how to string and tune the your instrument. Unlike Western musical instruments that are fairly standardised, the dilruba and the esraj are a bit flexible in this matter. We can say that most dilrubas are designed to work in a range from C-D. C# seems to be ideal. Does this mean that you have to string and tune your instrument specifically for this key? No, you do not. Your application will be the most important factor in deciding how you will string and tune the instrument.

In real world situations, you will be called upon to play at different times and in different keys. There is always the possibility of simply getting a different instrument for each key; but more often than not, you are just going to have to make do with what you have. Here are a number of approaches and situations that you might consider.

Solo – If you are only going to be playing your instrument as a solo instrument, then your choice of key is very clear. You will tune it somewhere near C#. This is where the instrument was designed and built to work best.

Re-Key Instrument – There are many situations where you wish to permanently reset the key of your instrument. Let us say that you are only going to use it to accompany a single person; this is a very common reason to do this. Let us say that for accompaniment reasons you wish to have one instrument set high for the accompaniment of women and another set low for the accompaniment of men; this would also require a permanent shift of key for one, or perhaps even both instruments. Let us say that you do studio work, and the only way you can guarantee to be able to handle any job that comes your way is to have a dilruba or esraj in each of the five black keys (i.e., kali ek, kali do, kali teen, kali char, kali panch); again you are going to have to permanently retune your instruments. These are all common reasons to permanently reset your instruments key. (I have two dilrubas, and one esraj, one which is set to C#, one is set to G, and one which is set to my wife’s key of A#).

This is all very well but what are the practical considerations in permanently changing the key on your key on your instrument. Let us briefly look at some of these considerations.

If you wish to change anywhere from C-D, there is no need to rethink your string gages.

If you are wishing to tune down to a range of G-B, or up to D# to F, then you should give very careful consideration to your string gauges.

Completely changing the key of the instrument involves extremely serious considerations and is something you should not just jump into. In theory, any instrument can be re-strung to accommodate any pitch. But as a practical matter you need to look at variations in size to see what is appropriate. If you are taking your instrument down in pitch, you might wish to purchase a larger instrument. You may even wish to look at a taus (i.e., mayuri veena) if you really want a low range.

It is always safer to re-key an instrument on the high aside rather than the low side. Just remember to remove all of the strings and replace them with a finer gauge. This will allow you to increase the pitch without increasing the tension on the instrument. There are of course practical limits as to how high you can take the instrument. Already the gauges of some of the strings are approaching the thinnest that are commercially available. If you attempt to take it much higher, you might need to rethink your overall approach to tuning.

Temporary Re-Keying your Instrument – The dilrubas and esrajs are accompaniment instruments. It is not at all unusual to accompany one person this weekend and another person the next. In such situations the key is unlikely to change within the performance, but it may change from day-to-day or week-to-week. In this situation it is possible to keep the sympathetics (both jawari and tarafdar) at a particular gauge, but switch out the main strings according to the situation. This will require being creative in the use and tuning of your sympathetic strings, but you have the advantage of being able to temporarily set your instrument to another key by only changing a few strings. In most case you can get by, just by switching out the first and second strings and then being creative as to what to do with strings three and four.

I have a dozen strings that I have carefully established what each string will tune to, and I do not hesitate to do this when these situations arise. If the replacement strings are carefully selected, you can change the strings and thus change the key without changing the tension exerted against the bridge. Therefore, if your sympathetic strings are tuned chromatically, you do not even need to do a major job of retuning them either.

Each Song in a Different Key– This is the most challenging situation of all. Unfortunately is also common if one is playing for film songs. For this situation, there is seldom a requirement for anything more substantial than a small interlude here and there. In these cases, the easiest thing to do is to be a bit creative on the tuning of the sympathetics (e.g., chromatic tuning) and learn to play your Sa from frets other than the seventh fret. All in all, it is a very workable solution to this problem.

Final Comments On Tuning

We have discussed a great length the conceptual issues concerned with the tuning and the dilruba and esraj. Not everybody is going to be faced with the same set of problems, Not everybody will be faced with the same requirements, therefore not everybody will address the issues in the same way. There has been no attempt to tell you what to do, but we have tried to lay out a number of different approaches that should be considered. Ultimately you should try all of them and see what works for you.

| STRINGING AND TUNING THE DILRUBA AND ESRAJ Section 1 – Introduction Section 2 – Basic Concepts of Tuning Section 3 – Overview of Strings Section 4 – Dilruba/Esraj Strings Section 5 – Tools Section 6 – Stringing the Base Section 7 – Stringing the Tuning Pegs Section 8 – Tightening the Strings |

Other Sites of Interest

How Does Music mean? Embodied Memories and the Politics of Affect in the Indian Sarangi

Bowed strings and sympathy, from violins to indian sarangis

Let's Know Music and Musical Instruments of India

Master Musicians of India: Hereditary Sarangi Players Speak

The North Indian Classical Sarangi: Its Technique and Role

Kamanche, the Bowed String Instrument of the Orient

The Acoustic Dynamics of Bridges of Bowed Instruments (An Outline of Comparative Instrument-Making)

The Natural History of the Musical Bow

Bharatiya Sangeet Vadya (Review)

Catalogue of Indian Musical Instruments

Fractal dimension analysis of audio signals for Indian musical instrument recognition

Natural synthesis of North Indian musical instruments

Recognition of Indian Musical Instruments with Multi-Classifier Fusion

The Tagore collection of Indian musical instruments

Improvement of Audio Feature Extraction Techniques in Traditional Indian Musical Instrument

East Indians musical instruments