Bollywood dance is the dance-form used in the Indian films. It is a mixture of numerous styles. These styles include belly-dancing, kathak, Indian folk, Western popular, and “modern”, jazz, and even Western erotic dancing. In this web page, we will look at Bollywood dance and place it within the commercial and artistic framework of the South Asian film world.

What Is Bollywood Dance?

Bollywood dance is a difficult topic to discuss because it is hard to pin down. Its exact definition, geographical distribution, and stylistic characteristics are amorphous. However in spite of all of this, it is surprisingly recognisable.

Let us begin by discussing the term “Bollywood”. In the strict sense the term “Bollywood” refers to the Hindi culture, art, and film industry from Bombay. The other film centres of South Asia are often referred to by their own designations (e.g., Lollywood (Lahore), Tollywood (Andhra Pradesh)). However since the Bombay Hindi film industry dwarfs the other productions centres, the term “Bollywood” is generally extended to mean the entire South Asian film culture. For the purpose of this web-page, we will use the more general meaning.

The international appeal of Bollywood dancing is something that has been many decades in the making. Originally it was found only in places that had a significant consumption of Indian films (i.e., Former Soviet Union, and the Middle East). But a few years ago it started to become chic in Europe, and today it is rising in popularity in the US, and Canada. Today, dance schools that teach this style may be found in most major cities.

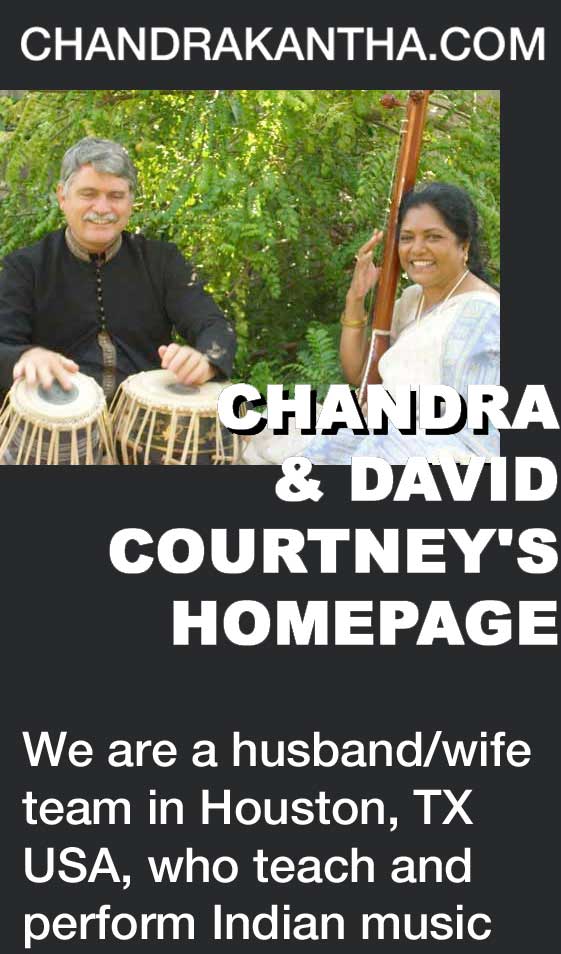

Bollywood dancing is the style of dance which developed in the Hindi film industry

Song and Dance In Indian Films

It is important to understand the relationship between theatre, music and dance in South Asia. Unlike the West, where the “musical” is considered to be just one of numerous genre, South Asians have a very difficult time conceiving of any theatrical or film endeavour that does not have music and dance. Films that are produced along the Western vein (sans music and dance) are consigned to the “art-film” category and generally meet with very limited commercial success. The only theatrical genre where song and dance are not expected, appears to be modern TV dramas. (i.e., “soap operas”). The unbroken tradition of linking theatre, music, and dance is traceable all the way back to the Natya Shastra (circa 2nd century BCE.)

Bollywood films must have song and dance, so it is reasonable to look into the styles of these dance forms. It turns out that this does not tell us much, because of the large number of dance styles that have been enfolded into it. Furthermore, Bollywood dancing has changed tremendously over the years.

Traditional Dance Elements

Films before 1960 tended to draw heavily on classical and folk dance. Since neither “classical dance” nor “folk dance” are homogenous entities, one naturally expects to find considerable variations. Not surprisingly, early films from south India tended to show a lot of influence from Bharat Natyam and Kuchipudi while Hindi/ Urdu films tended to show strong influences of Kathak or the “mujara” dances that were associated with the tawaifs. Although these influences continue today, they seem to have become mixed with many more dance styles and have at time become unrecognisable as to their origins.

Scene from Pakeezah

Choreographers

Choreography is not a field that gives a lot of fame. It is a demanding job, and one that is largely out of the public eye. But one must never forget that the actors and actresses do not just get in front of the camera and dance spontaneously. Someone has to create the number.

The Indian film industry has been graced with many great talents in the past. Some notables were, B. Sohanlal (“Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam”, “Jewel Thief”, Chaudhvin ka Chand”), Lachhu Maharaj (“Mahal”, “Pakeezah”, “Moghul-e-Azam”), Chiman Seth (“Mother India”), Krishna Kumar (“Awaara”, “Madosh”, “Andaaz”) and a host of others.

Today there are a number of choreographers who continue this tradition. Some who come to mind are Shiamak Davar (“Taal”, “Bunty aur Bubli”, Dil to Paagal Hai”), Saroj Khan (“Baazigar”, “Soldier”, “Veer Zara”), Ahmed Khan (“Rangeela”, Pardes, Mere Yaar ki Shadi Hai”), Raju Khan (“Lagaan”, Krrish), Vaibhavi Merchant (“Dhoom”, “Swadesh”, “Rang de Basanti”), Remo (“Jo Bole So Nihal”, “Pyar ke Side Effects”, “Waqt”), or Farah Khan (“Kabhi Khush Kabhi Gham”, “Monsoon Wedding”, “Dil Chahta Hai”).

Farah Khan, choreographer for “Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai”, “Dil Se”, “Kuch Kuch Hota Hai”, “Dil Chahta Hai”, “Asoka”, and “Monsoon Wedding”

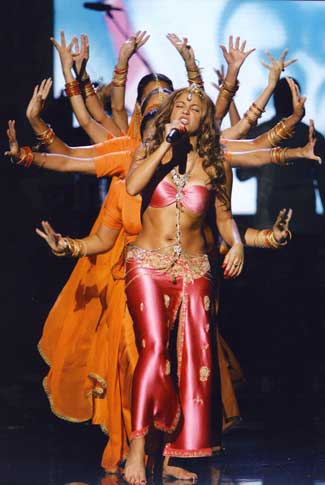

Costume

Clothing and costume are an extremely important element of the Bollywood dance. To a very great extent it will determine the “feel” that the dance will have in the film. With the right costume, one can do many things. If the film is a period piece, the proper costume goes a long way toward giving the feel of that period. If one is trying to make the dance scene dream-like or surrealistic, then obviously one goes for costumes that in no way relate to the clothing found in real life. If you are trying to give an erotic sizzle to an item number you can…. well you can figure that one out for yourself. Costumes can also be used to reflect the latest fashions, thus reinforcing the topicality of a dance number.

Proper costumes contribute to the overall “feel” of the dance

Over the decades many great artists have excelled in the field of costume design. In recent times Manish Malhotra (e.g., “Kabhi Alvida Na Kehna”, “Veer Zaara”, “Kal Ho Na Ho”), Neeta Lula (e.g. “Devdas”, “Mission Kashmir”), or Bhanu Athaiya. (“Swades”, “Lagaan”, “1942: A Love Story”, “Gandhi”) have made great names for themselves. But these artists are only part of a long tradition which extends back for about a century.

Romantic Numbers and Duets

No Bollywood film would be complete without a song and dance between the hero and heroine. As a matter of fact, no Bollywood film would be complete without MANY songs and dances between the hero and heroine. As a general rule, these scenes are the romantic numbers, the playful numbers, and the longing / sad numbers. One may also find songs about holidays, (e.g., Holi), Mother India, the moon, or other topics; but these are far less common.

The romantic number has been the cornerstone of the Hindi film since the first talkies. But dance has generally not been a strong part of these numbers. Historically, the hero and heroine simply wandering around at night in a garden. If the camera made strategic moves off-screen to shots of birds and trees, this was quite enough to suggest activities that the censors might not approve of.

Scene from “Pyar Ke Side Effects”

Closely related to the romantic number is the playful number. It is sometimes hard to separate the romantic from the playful because in both cases, the hero and heroine are expressing their undying love for each other; however the playful numbers rely much more heavily upon dancing. In the early days, there was an awful lot of dancing around trees. (I really do not know what Freud has to say about trees). However today, such playful numbers tend to revolve around exotic foreign locales and inexplicable changes in clothing.

The dance styles of these playful numbers has varied considerably over the years. Originally they may have revolved around classical or folk dance, but today, Bollywood has developed its own corpus of material. In the early days, some of these moves were really rather hard to class as dancing. The spastic deliveries of songs by Shammi Kapoor came to mind. Still, from these random spastic jerks and jumping around, identifiable moves began to develop. Today the playful love song has matured into an identifiable set of moves, some of which may be shared by other dance traditions around the world, but others are unique to Bollywood.

Shammi Kapoor’s … er… “unique” style.

Sometimes elaborate “Busby Berkeley” style dance numbers are used for the playful numbers. These numbers revolve around a number of dancers, usually female, dancing with military precision.

Eroticism and Bollywood Dance

The commercial power of sex was recognised by Indian film distributors very early on. As early as 1932, the erotic elements in “Zarina” were creating a public outcry, calls for greater censorship, but more significantly, lots of money for the cinema houses.

The obvious question was of course how to handle erotic content. It was clear that an element of eroticism was required for commercial success; however the puritanical nature of Indian society would not tolerate the heroine behaving in any immodest way. Three formulas developed in order to fulfil this requirement, these were the rape scene, attempted seduction, and the item number.

The rape scene has fallen out of fashion, but from the late 1950s through the 1970’s it was an essential element for any massala film. In this approach, an ingenue or some other secondary female character, was raped. This fulfilled two requirements: it provided the necessary sexual titillation in order to assure distribution, and at the same time it was a convenient dramatic device to establish the villain’s character. Although this topic is certain worth further discussion, it is beyond the scope of a page on Bollywood dancing.

In the 1960s a different approach to providing the necessary erotic titillation was sometimes used; this was the attempted seduction scene. In this scene, the vamp, would attempt to seduce the hero by way of her song and dance. Naturally, the hero would not succumb to the charms of this vamp, thus allowing him to marry the heroine five reels later. This approach was especially convenient for producers during this period, because they could introduce as much eroticism as the censors would possibly allow, yet the hero’s rejection of the seductress would always be considered a testament to the powers of traditional Indian values.

Dances were often employed in the attempted seduction scene. The style would of course vary according to the prevailing artistic norms, but they were always very suggestive.

Undoubtedly the artistic high point in the delivery of eroticism in Bollywood films was the development of the “item number”. The item number works like this. You bring in a secondary girl (known as the “item girl”) who is able to act, sing and dance in an erotic manner, often for only one piece. This introduces the erotic element, yet maintains the heroine’s modesty.

It is interesting to note the way story lines, item numbers, and dance, have been handled over the years. In the early days, the hero just happened to go to a mehefil (gathering) where a tawaif (dancer-cum-prostitute) was performing. This obviously had nothing to do with story development, but it was a convenient way to graft the item number into the film.

In this early period, the item number would generally revolve around a kathak style of dance. However true to Bollywood form, this kathak piece would not necessarily be a good kathak, but was the substantially more suggestive mujara variety.

This method of introducing the item number proved to be a very practical and popular approach; in the 1960’s this evolved into the cabaret number. Dramatically, this required nothing more than having the hero go to a cabaret instead of going to a mehefil. Since Indian society was becoming a little bit more relaxed, it was not unusual to find the hero and heroine going to a cabaret together.

The cabaret scene is probably the most significant artistic and commercial example of the Bollywood dance. It may be considered to be the first truly ‘Bollywood” form. Where previous item numbers might have utilised traditional mujara dances, the cabaret dance was unique to the cinema. Although it is truly Indian, it does draw upon pre-existing elements, many of which were drawn from Western “modern” dance forms of the 1960’s.

Undoubtedly the reining queen of the cabaret dance was Helen. She was born Helen Jairag Richardson, of mixed Anglo-Indian-Burmese descent. She started dancing and acting in the 1950s, and by the 1960s was the undisputed queen of the item girls. However by the 1970s, item numbers were going to the younger girls. By the 1980’s the downplaying of the item girl from the standard formula, along with Helen’s age, put her career on the rocks. Today her career has begun to turn around as she is making the transition from “item” roles to elderly “mother / mother-in-law” roles.

The queen of the cabaret – Helen

Although Helen is the most famous item actress, she was part of a tradition that extended before and survived afterwards. Bindu, Shashikala, Silki Smita, Aruna Irani, Jaymalini, Jyothilaxmi, have all made a name for themselves to some extent by doing item numbers. Today, the mantle is being taken up today by artists such as Kareena, Malaika or Sameera.

The relationship between the “item number” and the story line is interesting; it is simply grafted onto the film. It has no connection to the story line. Virtually any item number could be interchanged with any other item number, in any film, and it really would not make any difference.

It is interesting to note how item numbers have evolved. The more relaxed attitude toward eroticism in modern films means that one does not have to rely upon a secondary item girl in order to maintain the heroin’s modesty. Modern audiences seem comfortable with the heroine dancing very suggestively, where previous generations would have considered this to be scandalous. Therefore, item numbers are starting to be used for other purposes. One function is to bring in cameo appearances of big name artists. But when the item number is used to provide erotic titillation, it is usually at a very high level of eroticism. Even modern film audiences might be uncomfortable with their heroines exhibiting a level of abandon which is sometimes found in today’s item numbers.

The business reasons behind these modern hyper-erotic item numbers seems to be complex. In some ways, they are aimed at young male Indian audiences. However, it is very clear that the demands of the Middle Eastern market play very heavily into these decisions.

Item number from “Ram Gopal Varma Ki Aag”

The dance style of these modern hyper-erotic item numbers is very different from the item numbers of the past. Today the overriding influence is the Western erotic dancer. Traditional dance moves seem to be passé in these cases.

Conclusion

Bollywood dance may be seen as being on the ascendency in the world markets. Much of this is due to the ever expanding Indian diaspora, but a significant proportion comes from non-Indians who for whatever reason, are taken by the exotic, larger than life qualities inherent in it.

Selected Video

Other Sites of Interest

Bollywood's India: A Public Fantasy

Hindi Film Songs and the Cinema

Framing the Body and the Body of Frame: Item songs in popular Hindi cinema

The role of a song in a Hindi film

Story, camera and movement in Hindi film dance

Representation of Female Characters Through Item Songs in Selected Hindi Movies

Everyday life, everyday songs: a re-valuation of song sequences in popular Hindi films of the 1950s

An Analysis of the Characteristics of Modern Bollywood Musicals (Spanish)

The Use Of Melodic Scales In Bollywood Music: An Empirical Study.

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas

‘Bollywood Flashback’ Hindi film music and the negotiation of identity among British‐Asian youths

Re-embodying the “Classical”: The Bombay Film Song in the 1950s

"Suku suku what shall I do?" : Hindi cinema and the politics of music in Trinidad