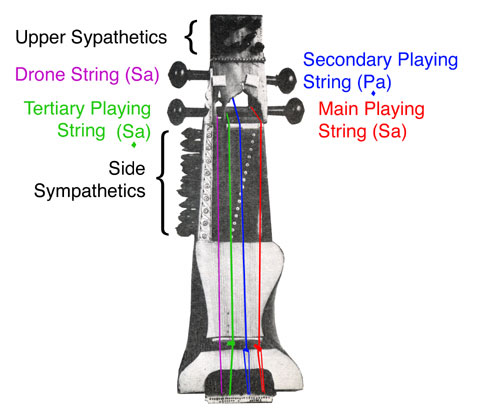

Sarangi is a common representative of vitat class of musical instruments. It has three to four main playing strings and a number of sympathetic strings. The instrument has no frets or fingerboard; the strings float in the air. Pitch is determined by sliding the fingernail against the string rather than pressing it against a fingerboard (like violin). This instrument is extremely difficult to play, as a consequence its popularity is on the decline. This instrument has traditionally been associated with the kathak dance and the vocal styles of thumri, dadra and kheyal. It was also greatly associated with an Indian version of the geisha tradition, known as the tawaif.

Definition

The origin of the term “sarangi” is not exactly clear. The most quoted etymology of the word says that means “a hundred (sau) colours (rang)“. The reference to the multiplicity of colours is often said to refer to the richness of the sound of the instrument. However it should be mentioned that this etymology is not universally accepted. Some suggest that it is derived from the Sanskrit word “Sarang” which is a spotted deer; this last etymology seems somewhat doubtful. All of this may be interesting, but what about the instrument itself?

The exact definition of the term “Sarangi”, is somewhat flexible. In its most general form, it refers to any unfretted, bowed Indian instrument, which has a bridge resting on skin or some other membrane. This term may be acceptable to the lay public, but for practising musicians as well as scholars, this term is unacceptably broad. The general use of the term encompass instruments such as the saringda, chikara, and the kamancha. For these web pages, we will use a more restrictive definition of the term. Therefore in these pages, we will be referring to the more boxlike members of this class, while the other members will be discussed in their respective pages.

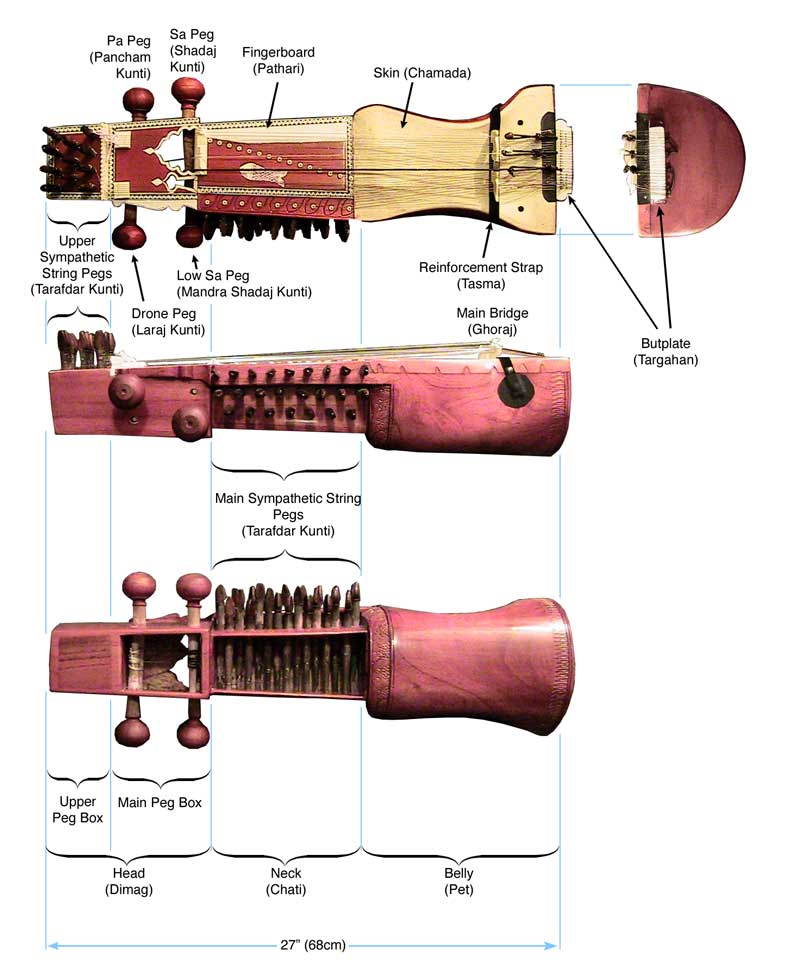

Parts of Sarangi

In this section we will go over the parts of the sarangi. Where available, we will give common Hindi / Urdu names for the parts. However the reader should be aware that the linguistic diversity of South Asia makes it impossible to pin down any standardised nomenclature.

| Are you interested in a secular approach to teaching Indian music. |

|---|

Indian music is traditional taught in a fashion that is linked to Hindu world views. But there are situations, often in schools, where this approach may not be the best. In such situations The Music of South Asia may be the best resource for you. |

Tuning

There are as many variations on the tuning of the sarangi as there are players. (Can you say “hyperbole” boys and girls?) This is typical of the philosophy of tuning that one encounters with most Indian stringed instruments.

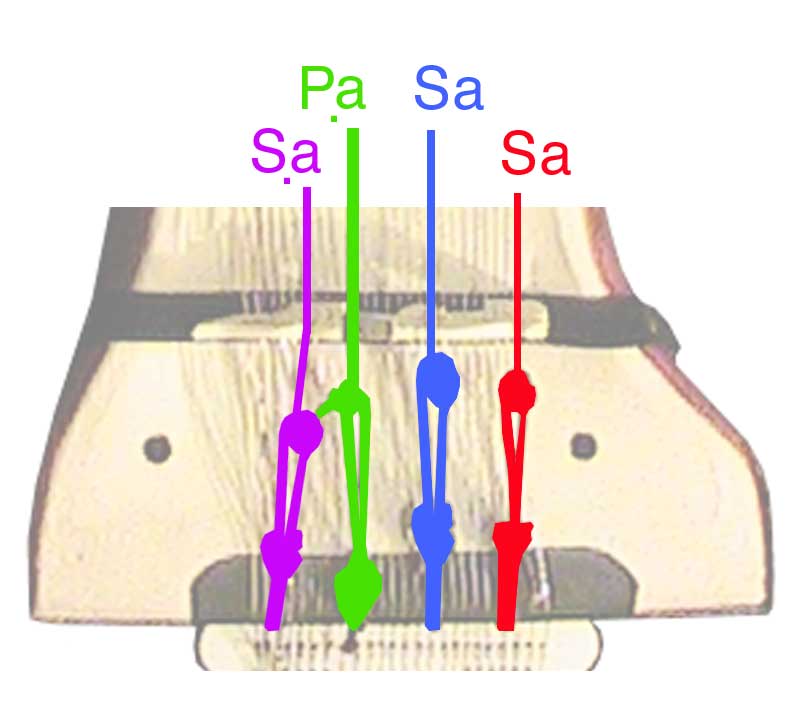

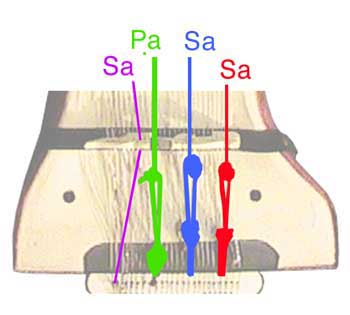

Standard Tuning – The most common approach to tuning the sarangi is shown below:

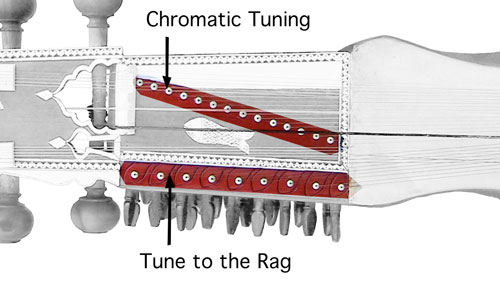

There are a number of different sets of strings. There are three playing strings, one drone string and two sets of sympathetic strings. The tuning of Sa, lower Pa, and low Sa, would be the most basic for the main playing strings. The drone string will usually be tuned to Sa, but even Ma or Pa is frequently found. The tunings of the sympathetic strings are so numerous that it is impractical to even attempt to describe them all. However, one normal approach is to tune one bank of the side sympathetics chromatically, the other bank of side strings to the rag, while the upper sympathetics may also be tuned to the notes of the rag.

Tune one bank of tarfdars to the rag, and tune the other chromatically

There are a number of alternative tunings that we should probably be comfortable with. However for a frame of reference, let us return to our common tuning.

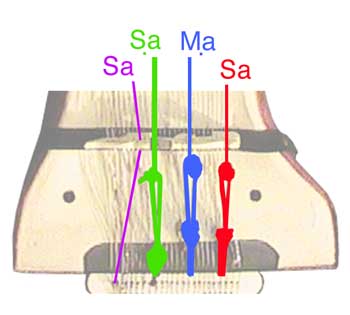

Alternative Tuning #1 (Sa Ma Sa Sa) – Our common tuning works well for rags which have the Pancham; unfortunately, many times Pancham will not be present. In such cases it is fairly common to find Shuddha Ma used in the rag. Although you can still tune the sarangi as per the common tuning, you will probably find the tuning below gives a much better sound:

There are rare cases where Pancham is not present and the Madhyam is Tivra. It does not follow that the second string should be tuned to Tivra Ma. This sort of thing is just not done in North Indian music. In such rare cases, you will probably just revert to the common tuning.

Alternative Tuning #2 (Inverted Tuning) – Let us examine the previous tuning in a different light. If we just think of it slightly differently it assumes a totally different character.

Think of all the times you have had a tanpura tuned to Ma (e.g. to accompany Malkauns, Chandrakauns or any similar rag), and after a while, it starts to sound a little confusing. It starts to sound like the Ma is Sa, and the Sa starts to sound like Pa. However it is all in a different key. It is interesting to note that this is not just an illusion; it really has changed, if we choose to define it as such. This process is known as an “inversion”.

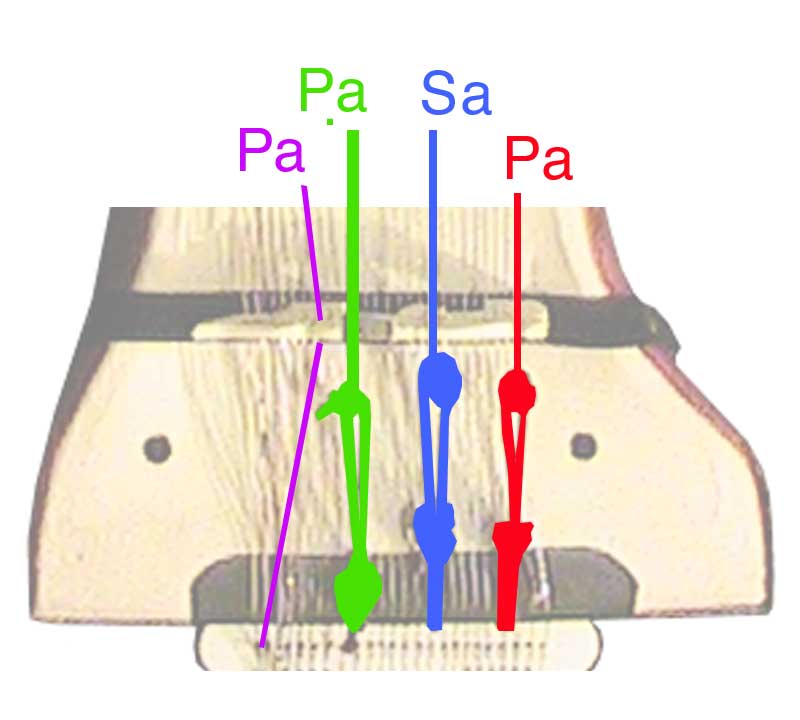

Now let us apply the concept of inversion to alternative tuning #1. We do not change any of the tunings, we will only change the way we define it in our mind. If we take the 2nd string (Ma) and redefine this so we now consider it to be Sa, then our other strings are also redefined so that the reflect the diagram below:

This approach has some very practical benefits. Sarangi is primarily known as an accompanying instrument for the voice. Unfortunately the numerous strings of the instrument make it ill suited towards this task. People sing in a a variety of keys, while a common tuning of the sarangi is limited to just a couple of steps. There is always the option of switching the strings out; but sometimes this is just too awkward. Our inverted tuning allows us to shift the key of the sarangi down by about half an octave without changing any strings at all. So just as the concept of inversion allows us to extend the usable range of a tanpura, the same inversion allows us to extend the usable range of our sarangi.

Alternative Tuning #3 (Folk Tuning) – Sarangi is often played in a folk style; in such cases the drone is especially important. When I talk of drone, I do not mean the resonance from the sympathetic strings, but I mean the simultaneous playing of two strings. Ram Narayan was particularly fond of this approach. In the common tuning, the only real way to affect this drone is to play the second and first string simultaneously, but use the second string to play the melody while the first string (Sa) provides the drone.

This sounds nice, and is workable as long as you confine the range from low Pa to Pa in the middle octave: however this is just a temporary work-around. If you play in a folk style, you will probably find that this stringing and tuning just does not give you that heavy drone which is so characteristic of the folk style. In which case you may wish to consider the following tuning.

This allows you to use the first string as your main melody string, and constantly play the second string as your drone. Should you need to go into the lower octave, then your third string becomes your melody string, while your second string remains the drone string. Notice that the third string only allows you to reach down to Pa in the lower octave. In the rare situations that you must play the lower tetrachord of the low octave (i.e. Sa, Re, Ga, Ma) then you can reach down and bow the fourth string and play that as your playing string. You would probably not attempt to give any drone when playing off the fourth string because it would necessitate shifting the drone from the Sa down to the Pa of the third string. An interesting effect admittedly, but generally not within the musical culture of Northern India.

This tuning is a very good way to allow your sarangi to play the folk styles, but it does have some very significant drawbacks. The instrument must specifically be restrung to use this type of tuning. You can’t just switch back and forth without changing the strings. Furthermore, since you are shifting the fourth string up to the top of the bridge, this will necessitate some very significant modifications to your bridge. These modifications are not for the faint of heart!

Alternative Tuning #4 (Folk Tuning) – One may consider a hybrid between the last tuning and our common tuning. This is shown below:

We see that in this tuning, we retain the thin metal string (usually brass or bronze ) of our common tuning; but our 1st 2d, and 3rd strings, are like our previous folk tuning. This tuning only requires us to switch out a few strings; it requires no work on the bridge. However, It does have the disadvantage that we lose half an octave of usable range of the instrument. Never-the-less, many may find this a more accessible way in order to get the drone string in close proximity to the main playing string.

I must emphasise that these last few tunings are only to be used if we wish to play a sarangi in a folk style. For most people the common tuning which was illustrated at the top of this page, is the best approach.

| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the first volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Fundamentals of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Fingering

Fingering is a very important topic when learning the sarangi. However before we get into the fingering of the instrument, we need to have a basic idea as to where the notes lay. (For the rest of this page we will be presuming that the standard tuning is employed for our sarangi.) Refer to the following illustration:

The illustration above shows us where the notes are. In this illustration we see the three octaves of the instrument. Notice that the first tetrachord of the lower octave (i.e., Sa through Tivra Ma) is played with the heavy third string. The middle sized second string plays the upper portion of the lower octave. And finally, the thin first string plays the remaining two octaves. Once we have familiarised ourselves with the positions, we next turn our attention to the actual fingering.

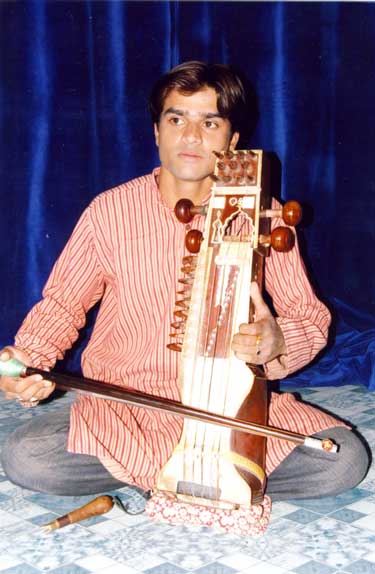

The first thing to remember is that the strings are not stopped against the fingerboard, but instead are simply stopped by sliding the string against the nail, cuticle, or area under the first knuckle. The actual position seems to be a question of personal taste. I for one, like to slide the string against the nail, I find it does the least damage to your fingers. Most people use the area around the cuticle, and some, as in the picture below, use the area above the cuticle.

The first three fingers of the left hand will be used to stop the string. Sometimes the string is stopped with the first finger (index finger). This is illustrated with the picture below:

Sometimes the string is stopped with the second finger (middle finger). This is illustrated with the picture below:

Sometimes it is stopped with the third finger (ring finger). This is illustrated with the picture below:

Now the obvious question arrises as when to use which finger. India is big county and one may find considerable differences of opinion. I do not like to pontificate on these matters, so I will discuss several of the approaches here.

The table below is probably the most common approach to fingering.

| STANDARD FINGERING | ||

| NOTE | STRING | FINGER |

| Sa (Lower Octave) | 3rd | Open |

| Komal Re (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 1st |

| Shuddha Re (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 1st |

| Komal Ga (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 1st |

| Shuddha Ga (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 1st |

| Shuddha Ma (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 2nd |

| Tivra Ma (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 2nd |

| Pa (Lower Octave) | 2nd | Open |

| Komal Dha (Lower Octave) | 2nd | 1st |

| Shuddha Dha (Lower Octave) | 2nd | 1st |

| Komal Ni (Lower Octave) | 2nd | 2nd |

| Shuddha Ni (Lower Octave) | 2nd | 2nd |

| Sa (Middle Octave) | 1st | Open |

| Komal Re (Middle Octave) | 1st | 1st |

| Shuddha Re (Middle Octave) | 1st | 1st |

| Komal Ga (Middle Octave) | 1st | 1st |

| Shuddha Ga (Middle Octave) | 1st | 1st |

| Shuddha Ma (Middle Octave) | 1st | 2nd |

| Tivra Ma (Middle Octave) | 1st | 2nd |

| Pa (Middle Octave) | 1st | 2nd |

| Komal Dha (Middle Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Dha (Middle Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Ni (Middle Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Ni (Middle Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Sa (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Re (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Re (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Ga (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Ga (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Ma (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Tivra Ma (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Pa (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Dha (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Dha (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Ni (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Ni (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Sa (2 Octaves Higher) | 1st | 3rd |

There is a variation to this fingering that was used by the Ram Narayan. It differs from our standard fingering as to when one shifts from the first finger (index) to the second finger (middle finger). By Ram Narayan’s own admission it is a non-standard approach, and under any other circumstance we would dismiss this as being a somewhat idiosyncratic technique. However Ram Naryan is considered unequalled in the 20th century for his skill and influence over the entire field of sarangi; therefore some attention to his technique is in order.

| RAM NARAYAN FINGERING | ||

| NOTE | STRING | FINGER |

| Sa (Lower Octave) | 3rd | Open |

| Komal Re (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 1st |

| Shuddha Re (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 1st |

| Komal Ga (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 2nd |

| Shuddha Ga (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 2nd |

| Shuddha Ma (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 2nd |

| Tivra Ma (Lower Octave) | 3rd | 2nd |

| Pa (Lower Octave) | 2nd | Open |

| Komal Dha (Lower Octave) | 2nd | 1st |

| Shuddha Dha (Lower Octave) | 2nd | 1st |

| Komal Ni (Lower Octave) | 2nd | 2nd |

| Shuddha Ni (Lower Octave) | 2nd | 2nd |

| Sa (Middle Octave) | 1st | Open |

| Komal Re (Middle Octave) | 1st | 1st |

| Shuddha Re (Middle Octave) | 1st | 1st |

| Komal Ga (Middle Octave) | 1st | 2nd |

| Shuddha Ga (Middle Octave) | 1st | 2nd |

| Shuddha Ma (Middle Octave) | 1st | 2nd |

| Tivra Ma (Middle Octave) | 1st | 2nd |

| Pa (Middle Octave) | 1st | 2nd |

| Komal Dha (Middle Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Dha (Middle Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Ni (Middle Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Ni (Middle Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Sa (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Re (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Re (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Ga (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Ga (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Ma (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Tivra Ma (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Pa (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Dha (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Dha (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Komal Ni (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Shuddha Ni (Upper Octave) | 1st | 3rd |

| Sa (2 Octaves Higher) | 1st | 3rd |

Now we need to discuss how strictly any particular fingering is adhered to. If we were simply to play straight (i.e. “cut” notes) as one finds in Western music, then it would be possible to play all of the notes as specified above. However, it becomes readily apparent that with either of these above approaches, many types of ornamentation, in particular many slides (i.e., meend), are simply impossible. Therefore considerable latitude is extended to the fingerings.

One area where this latitude produces interesting technical results is in the playing of the second and third strings. Although the fingering charts described above showed the third string going only as high as Tivra Ma (augmented 4th), and the second string going only as high as Shuddha Ni (Natural 7th), in practice these strings are played considerably higher up into the scale. For instance virtually any ornamentation of the lower octave Pa, must played on the third string, and virtually any ornamentation of our middle Sa, must be played from our second string. This usable range of the second and third string is extended even further when we wish to play other meends. (e.g. lower Ni to Re as one would find in Yaman Kalyan which can only be played as a meed from the 2nd string.) There is no theoretical limit placed upon how high we can go on the third or second strings, but as a practical matter, one seldom goes more than a step or two beyond the ranges specified in our earlier fingering charts.

Photo Gallery

Selected Video

Other Sites of Interest

How Does Music mean? Embodied Memories and the Politics of Affect in the Indian Sarangi

Bowed strings and sympathy, from violins to indian sarangis

Let's Know Music and Musical Instruments of India

Master Musicians of India: Hereditary Sarangi Players Speak

The North Indian Classical Sarangi: Its Technique and Role

Kamanche, the Bowed String Instrument of the Orient

The Acoustic Dynamics of Bridges of Bowed Instruments (An Outline of Comparative Instrument-Making)

The Natural History of the Musical Bow

Bharatiya Sangeet Vadya (Review)

Catalogue of Indian Musical Instruments

Fractal dimension analysis of audio signals for Indian musical instrument recognition

Natural synthesis of North Indian musical instruments

Recognition of Indian Musical Instruments with Multi-Classifier Fusion

The Tagore collection of Indian musical instruments

Improvement of Audio Feature Extraction Techniques in Traditional Indian Musical Instrument

East Indians musical instruments