The Folksong of Northern Bangladesh

by Wing Commander Mir Ali Akhtar (Retired)

and

David Courtney ![]()

| Vaoaiya (Bhawaia): The Folksong of Northern Bangladesh Part 1 – Introduction Part 2 – Music and Texts Part 3 – Glossary, Misc., Works Cited |

Musical Characteristics

We must look at some of the musical characteristics of the vaoaiya folk-song. This will require an examination of the melodic forms, rhythmic forms, as well as forms of musical accompaniment.

Modal Characteristics – There are two common modes used in the vaoaiya. They are found in different parts of the country.

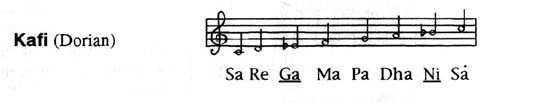

The first mode that we will discuss is found in the southern part of Rangpur. It is characterised by the minor third and the minor seventh. It may be expressed as follows:

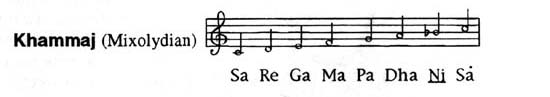

There is another common mode which is found in the northern part of Rangpur, Jalpaiguri, Coch-behar, Goalpara areas. It is exactly the same, except it is characterised by the use of only the minor seventh. It is shown below:

There are two points to keep in mind about these modes. One should note that neither of these modes have a name in the local dialects. Another thing to remember, is that these modes have been normalised to the key of C for notational convenience. These modes may be performed in any key which is convenient to the performers.

The register of these songs is generally limited to slightly over an octave. Although this may seem limited, people have proposed a number of practical reasons why this should be the case. The most obvious reason is to accommodate the varied musical capabilities of singers who are not professional musicians. But it has also been put forth that singing in the higher octaves would cause distress and agitation among the herds of the cows, buffalo herds, and elephants. Others have put forth an even simpler reason; why would a tired working folk, want to expend the energies to sing in the higher octaves?

We have discussed at some length the musical characteristics of the vaoaiya. We have seen that there are several modes in which they are performed. We should now turn our attention to the rhythmic forms.

Rhythm of Vaoaiya – The rhythmic system of South Asia is known as “tal”. It is structurally similar to Western concepts of rhythm, in that it has three main units of structure. There is the beat, the measure, and there is the cycle. However the emphasis is different in that in South Asia, the major emphasis is placed on the cycle, while the measure is considerably downgraded in importance. This has the practical result of making “mixed measure” extremely common in South Asia where it is a rarity in the West.

The rhythmic patterns used in vaoaiya is very typical of the folk music found throughout Northern India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The most common is Kaherava tal which roughly corresponds to the Western “common time”. This is generally classified as two measures of four beats each.

Another rhythmic form which is occasionally found is a rhythm named “Teora”. The term of course a cognate of Tivra, and indeed the abstract structure of Tivra tal is the same as the Bengali folk Teora. However, stylistically there is a difference between the folk Teora of Bangladesh, and the more classical Tivra tal found in the Hindustani system of classical music. Teora is generally considered to consist of three measures, of three beats, two beats, and two beats respectively. It is generally considered to have the structure:

XDhaa GheRe NagGa | 2TeRe KeTe | 3GoDi GheNe |

It has been suggested that perhaps this tal is a recent import into the vaoaiya. Older traditional vaoiayas are conspicuous in their absence and even today it is seldom heard.

There is also a three or six beat pattern which is commonly found in the region. Throughout most of Sub-Himalayan South Asia, this style is referred to as Dadra, but in this region it is referred to as “chotka”. Chotka is the outcome of early nineteenth century fusion of vaoaiya with Saontali Jhumur (3/4 time). This appears to be the result of a cultural mixing between the Santalis and the Rajbongshis.

The tempo of the vaoaiya folksongs vary. Songs related to bathan, moishal (buffalo herders) are of higher tempo than songs related to mahoot (elephant keepers). Songs related to garial and chilamari bondor carts are the fastest of all.

Ornamentation – There are two types of ornamentation which seem to be particular characteristics of the vaoaiya folk-song. One is a characteristic exaggeration of aspirated syllables, and the other is a type of yodelling referred to as “gola vanga”.

There is a peculiar type of ornamentation that is a characteristic of vaoaiya. This is called “gola vanga” which literally translates to “breaking the voice”. This type of ornamentation does not appear to have an Western equivalent. It has been described as yodelling; this probably is the closest approximation, because the technique is very similar. The major difference is that where yodelling involves a continuous trill of notes, the gola-vanga merely involves the sudden shift from one note to another note of suitable harmonic relationship. In other words, it is the linking of two distantly placed notes in a manner that you start with a high note and suddenly shift down to a distant note using the vocal technique of yodellers. The “gola vanga” ornamentation comes without effort to the native singers, but non-native singers generally have a difficult time with this.

The “gola vanga” form of ornamentation may have evolved from natural causes. It is suggested that singing as the cart rode upon bumpy and uneven ground would naturally cause such irregularities in the voice. After some time, such irregular pitch changes became a mandatory ornamentation for the vaoaiya.

The “gola vanga” ornamentation may be performed with several variations. For instance the harmonic relationship may be varied. It may be performed within middle octave, middle octave down to lower octave, in one octave within 2 to 4 notes. Its duration may also change; it may cover one, or several words.

There are actually two versions of gola vanga. In the Northern parts, the gola vanga is much slower than in the southern areas. Therefore where the faster cuts of the southern version resemble yodelling, the northern version is more of a glissando.

The “gola vanga” pitch change ornament is not the only type of ornamentation that is common in the vaoaiya; another extremely strong ornamentation is a highly exaggerated aspiration of the words. It has been postulated that this exaggerated aspiration was also originally the result of singing while riding a cart over very uneven ground, and that like the “gola vanga”, it too became a mandatory ornament for the vaoaiya.

Instrumental Accompaniment – The vaoaiya folk-song may depend primarily on the voice, but there is also a rich tradition of musical accompaniment. The common instruments used to accompany the vaoaiya and their classification is as follows:

(1) Chordophone group: are dotora; gholtong (i.e., khomok), sharingda; banshi (bamboo or reed flutes); bena.

(2) Aerophone group: are bombashi; mukhbashi (fipple flute); folk shehanai; folk beena (abolished now).

(3) Idiophone group: are kashi, mondira (i.e. manjira), khafi (i.e. large Manjira) kortal; Nupur (i.e., Ghungur or ghungharu).

(4) Membranophone group (Rhythm instruments): are dhol, khol, akhrai (a practice dholak); korka (jhorka).

Vaoaiya Lyrics

Example 1

Story Synopsis – On the Dhorla river bank, a trapper has fixed a trap. A male crane (boga), in his desire for the puti fish bait, flies in and gets caught. A red-goose (chokowa ponk-khi) sees this, and flies away and informs the crane’s mate (bogi) about the situation. Upon hearing the distressing news, the she-crane (bogi) spreads her wings and flies to the Dhorla river bank. Upon seeing her trapped mate, she is at a lost for words as her mate will surely be dead soon. Here the proverb “sometimes silence is more eloquent than sound” proved to be true. With tears in both of their eyes boga and bogi see each other for the last time.

Sample lyrics one of the most popular/famous vaoaiya:

Sample-1

Bengali

- Fande poriya boga kande.

Fand boshaiche fandi re vai puti macho diya,

O’re macher lobhe boka boga pore urao diya re.

- Fande poriya re boga kore tanatuna

O’re aha-re konkurar shuta holu noa-ar guna re.

- Fande poriya re boga kore hai re hai,

O’re darun bidhi, shathi chai ra aji re.

- Aar boga ahar kore ashe aro pashe

Aar amar boga ahar kore dholla nodir pare re.

- Ooriya jai re chokoya ponkhi bogik bole thare,

O’re tomar boga bondi hoiche dholla nodir pare re.

- Ei kotha shuniya re bogi dui pakha melilo

O’re dholla nodir pare jaiya doroshon dilo re.

- Bogak dekhiya bogi kandere,

Bogik dekhiya boga kandere.

English Translation

- Being trapped he-crane is crying,

With puti fish trapper fixed the trap,

Oh foolish crane in greed of fish flies in.

- Pull and haul does the crane in trap,

O’h koncura thread becomes steal noose,

- Flying in the trap boga, regrets

“O” rude fate of mine, my mate parts”.

- Other cranes eat here and near

My crane eats on dhorla river bank

- Gesturing flying red-goose tells bogi

“Your boga is trapped on Dhorla bank”.

- Bogi, hearing that spreads wings

Reaches Dhorola bank and meets;

- Seeing boga bogi weeps.

Seeing bogi boga weeps.

Example 2

Synopsis of Song – A cart driver reflects upon the longing for his woman, and her longing for him, during the long monotonous ride to the Chilmari river port

Bengali

- Oki garial vai,

Koto robo ami ponther dike chaiya re.

Jedin garial ujan jay

Narir mon more jhuriya roy re.

- Oki garial vai

Haka gari chilmarir bondore.

Aar ki kobo dushker jala, garial vai.

Gathiya chikon malare.

Oki garialvai,

Koto kandim mui nidhuya pathare.

English Translation

- Oh cart driver dear,

How long I do await looking at path.

The garial drive upstream,

My women soul is gloomy, oh.

- Oh cart driver dear,

Drive cart to chilmari port.

And what to say of my grief,

Making lovely wreath,

Oh cart driver dear,

How long do I await in the vast barren land.

Example 3

Synopsis of Song – A unmarried woman reflects upon her cruel fate which has not sent her a husband

Lyrics of Song – printed copy of vaoaiya (collection-1898 A.D.).

Bengali

- Pothom jouboner kale na hoil more biya,

Aar koto kal rohim ghore ekakini hoiya,

Re bi dhi nidoiya.

- Halia poil more shonar joubon, moleyar jhore,

Maobape more hoil badi na dil porer ghore,

Re bidhi nodoiya.

- Bapok na kow shorome mui maook na kow laje,

Dhiki dhiki tushir oghun joleche dehar majhe,

Re bidhi nidoiya.

- Pet fate tao mukh na fote laj shoromer dore,

Khuliya deikhle? moner kotha ninda kore pore,

Re bidhi nidoiya.

- Emon mon more korere didhi emon mon more kore,

Moner moto changera dekhi dhoriya palao dure,

Re bidhi nidoiya.

- Kohe kobe hani naiko more tate,

Moner shadhe korim keli poti niyasathe,

Re bidhi nidoiya.

English Translation

- At dawning youth I was not by Hymen favoured,

How long still am I to remain single at home,

O fate marble-hearted!

- The full-blown flower of my golden youth

Yields to Malay’s breeze,

My parents have become my foes in not

Sending me to am

another’s homebound in his hymeneal,

O fate marble-hearted!

- My heart I can not open to my father for shame,

Mother I cannot press by maidenly modesty bound,

Slowly is love consuming my frame as fire within chaff,

O fate marble-hearted!

- Even though my soul give way to pressing

Love within, my lips never open for fear of shame,

if I give out the feelings of my heart, the folk would blame,

O stone-hearted fate!

- Such mind is mine, aught do I not care,

A youth to my heart would I find;

With him I fly to a distant clime,

O fate marble-hearted!

- Stain who will my name, aught do I not care,

To the fill of my heart will I enjoy the fine in my

Loves sweet company,

O fate marble-hearted!

Example 4

Lyrics of song – printed copy of vaoaiya (collection-1898 A.D.).

Synopsis of Song – These are the parting words of a wife to her husband, a merchant, on the eve of his sailing out to trade in distant places

Bengali

- Pran sadhu re,

Jodi jan, sadhu porobas,

Na koren sadhu porar ash,

Apon hate sadhu, andhya khan vato re.

- Pran sadhu re,

Kochar kori, sadhu, na koren bayi,

Porar nari, sadhu, apon noyay re,

- Pran sadhu re,

Je diya, sadhu, torongo dhar,

Sei diya, sadhu, balu-char re,

(O) Gohin dhare, sadhu, boya den nao, re.

- Pran sadhu re,

Pubiya pochchyia bao,

Ghopa chaiya sadhu nagan nao,

(O) Dar-i majhi, sadhu, akhen sadhu re,

- Pran sadhu re,

Jei diya sadhu, saudher mela,

Sei diya sadhu, chhanden gola, re.

(O) Bechi kini, sadhu, koren sabodhane, re.

- Pran sadhu re,

Tor ache sadhu, bapo vai,

More ovagir sadhu, keyo nai re,

(O) Kon dale, sadhu, dhoribe narir vora, re.

English Translation

- Dear merchant O,

if you go, merchant away from home,

Not do, merchant, other’s hope,

Own hand with, merchant, cooking eat rice, O.

- Dear merchant O,

In-corner of loincloth money, merchant, not do spend,

Other’s wife, merchant, will-kill soul (O),

- Dear merchant O,

What direction-in, merchant, have force,

That direction-in, merchant, sand bank O,

Deep-current in, merchant, carrying give boat, O.

- Dear merchant O,

Easterly westerly wind,

Sheltered-nook, seeing, merchant, moor boat,

Rower helmsman, merchant, keep careful, O.

- Dear merchant O,

What direction-in, merchant, merchandise of-gathering

That direction-in, merchant construct a-storehouse, O,

Selling buying, merchant, do with-care, O.

- Dear merchant O,

Thine are, merchant, father brother,

Me-of poor-soul-of, merchant, anyone is-not, O,

What branch, merchant, will-support wife’s weight O.

| Vaoaiya (Bhawaia): The Folksong of Northern Bangladesh Part 1 – Introduction Part 2 – Music and Texts Part 3 – Glossary, Misc., Works Cited |