It is well known that Indian music is based on an oral tradition. However, it is often erroneously presumed that this oral tradition precluded any musical notation. This is not the case. Musical notation, known as swar lipi, has existed in India in some form from the ancient Vedic age up to the modern Internet age. Unfortunately, the precision and expanse of such notation has been questionable until relatively recent times. Even in recent times, challenges are frequently encountered vis-à-vis the Internet and electronic media.

Historical Overview

Indian musical notation did not spring up suddenly. Today’s notation developed in spurts over several millennia. The major growth may have only been within the last two centuries, but it was predicated upon a long history of musical scholarship.

The Vedas – The Vedic hymns are arguably the earliest examples of musical notation. There are four Vedas: the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samveda, and the Atharvaveda. The Rigveda and the Samveda are of particular interest to us from a musical standpoint.

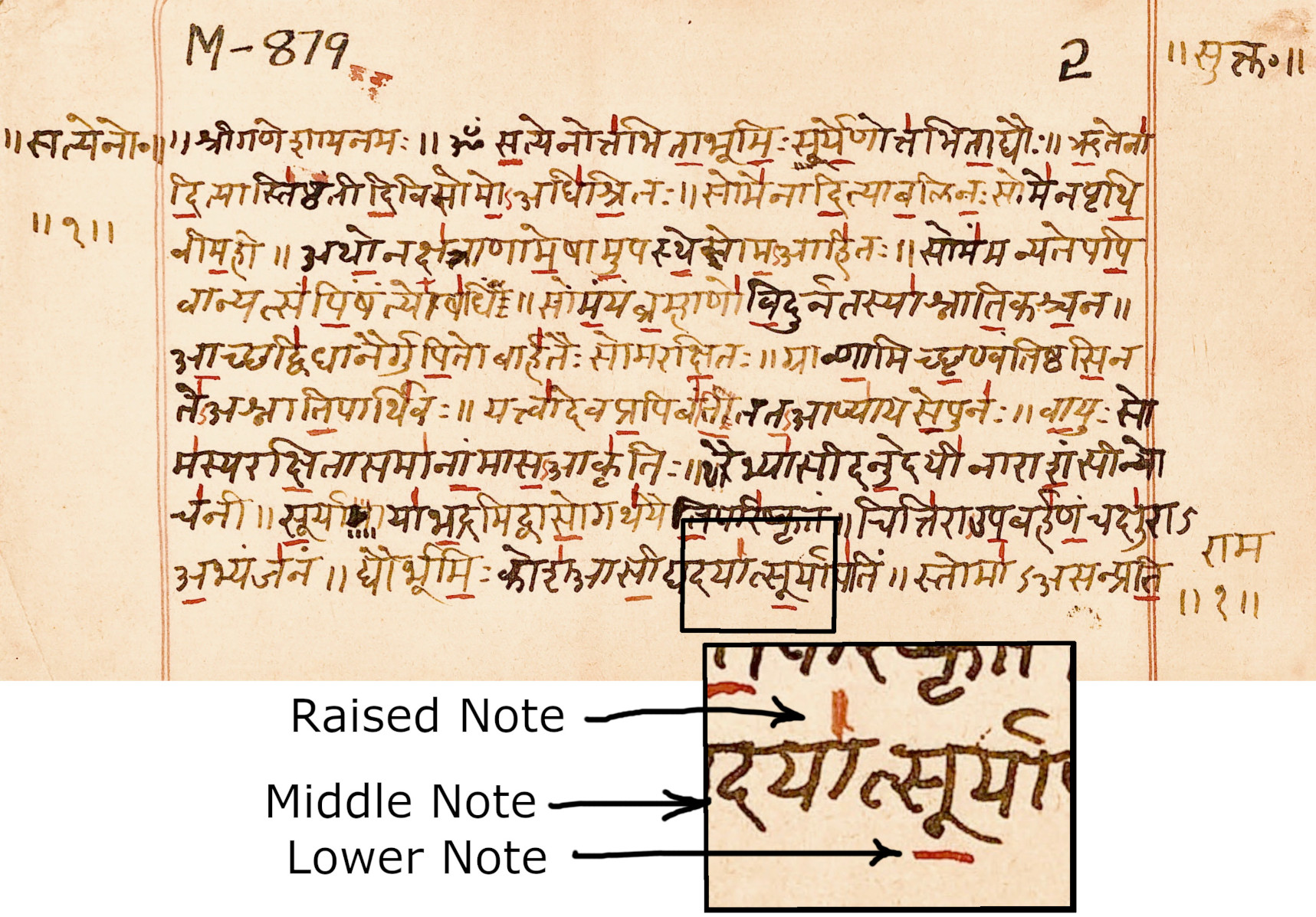

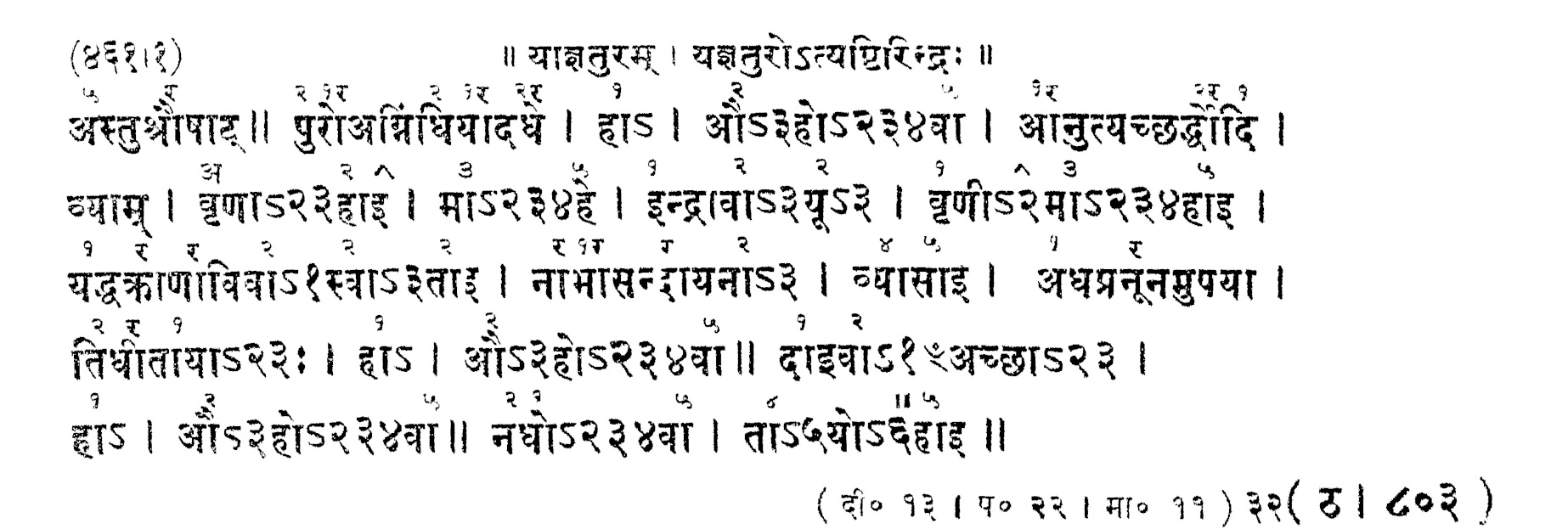

Below is a pre-1890 Devnagri reproduction of section of the Rigveda (Welch 2018).

The Rigveda, has a notation which revolves around three notes. There is a upper note which is designated by a vertical line above it, there is a middle note which has no mark, and there is a lower pitched note which is designated by a horizontal line underneath it. Unfortunately there is a lack of agreement as to what these notes are called. One school of thought has it that the raised note is the “swarita“, the middle note is the “udatta“, while the lower note is the “anudatta“. This is countered by another school of thought which has it that the raised note is the “udatta“, the middle note is the “anudatta“, while the lower note is the”swarita“. Opinions in this matter are often very strongly held, and discussions can become acrimonious. We are presenting both views without expressing any opinion.

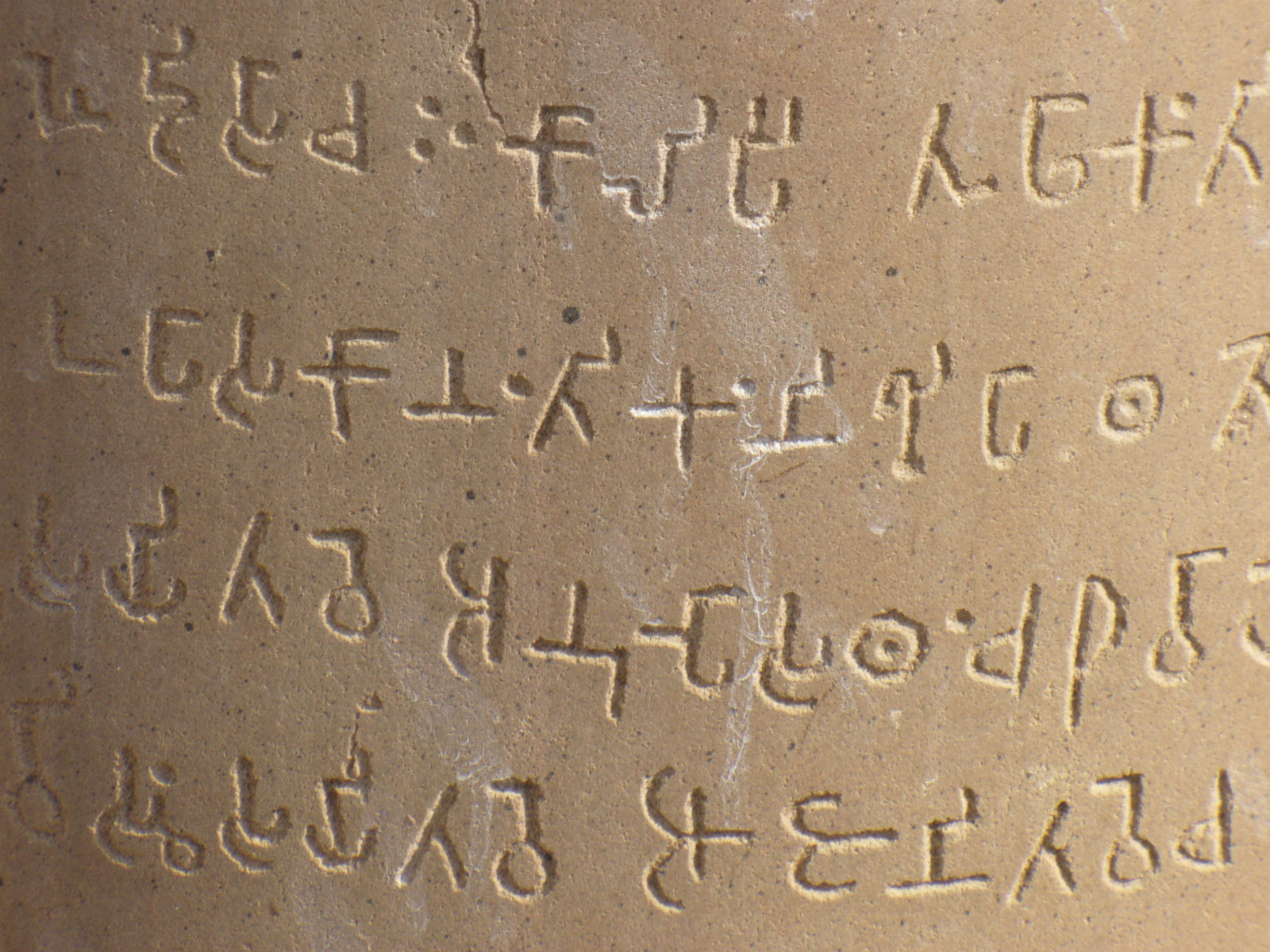

There are numerous questions which come to mind. For a very long time, Sanskrit has been written in the Devnagri script; but before this, the Brahmi script was used (see image below). Devnagri only dates to about the 1st-4th century CE. This brings up questions concerning the diacritical marks used to denote the musical pitch. Were these marks adapted from earlier Brahmi? Did they arise at the same time as Devnagri? Were they added during some period after the adoption of Devnagri?

These questions are particularly germane to this web page. The age of these musical diacritical marks may mark the beginning of musical notation in South Asia.

The Samveda – The Samveda introduces its own twists to the subject of musical notation. Unlike the Rigveda which had a very limited number of notes, the Samveda was a fully developed “song book” (Saletore 1985). Indeed it may be thought of as the Rigveda set to music (Klostermaier 1994)..

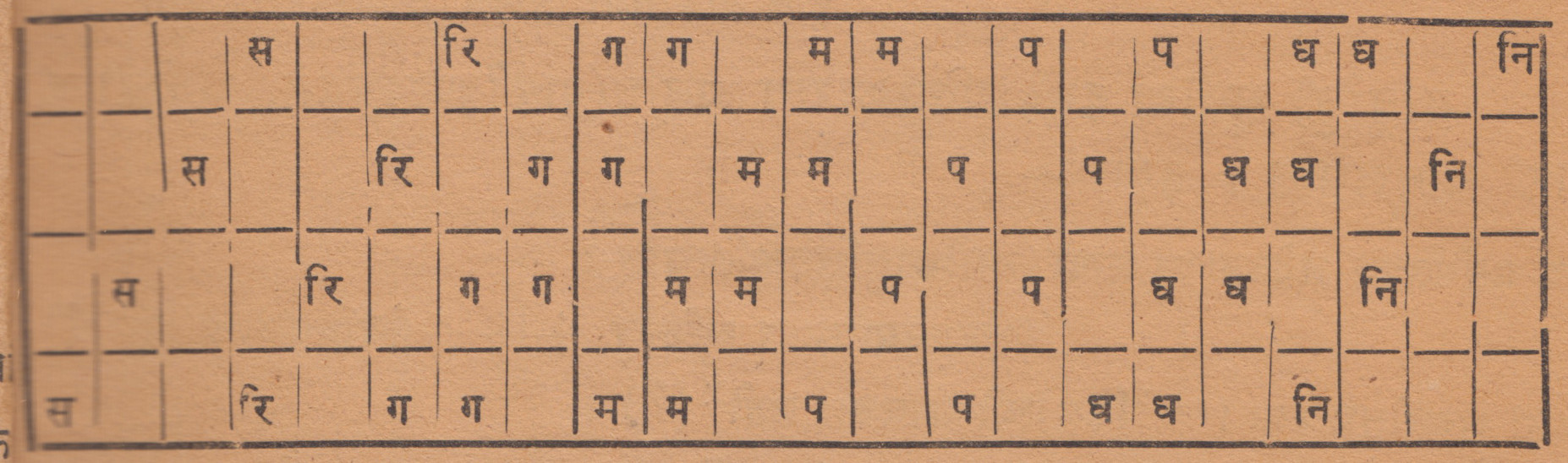

The Samveda used more than three notes; therefore the simple diacritical marks of the Rigveda were not sufficient. At some point in the past, numbers and other symbols were used to help specify the pitch, but this approach is not universal. Below is a text from the Samveda with numbers:

There are questions concerning the antiquity of this approach to the Samveda. It obviously does not extend back to the Vedic period. But how far does it go?

Mauryan Age to Start of Islamic Period – This is a very large period of Indian history. It extends roughly from 321 BCE to the start of the Muslim influence in about 1206 CE. This is an extraordinarily long period of time. Unfortunately very large lacunae exist in our knowledge of the music of this period. Numerous musical forms have come and gone without leaving a trace. There are however a few musical texts which give us tantalising glimpses of the musical culture. The most notable being the Natya Shastra by Bharata, Brihaddeshi by the sage Matanga, and the Sangeet Ratnakara by Sharangdev.

The Natya Shastra is the oldest surviving text on stagecraft in India. It is very difficult to assess its age; most reasonable estimates lay between the 3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE. However, one may encounter dates several centuries earlier or later.

Large portions of this work deal with music (Bharatamuni – undated). Obviously such discussions would be impossible without at least a rudimentary form of notation. Unfortunately the Natya Shastra was written in verse rather than prose. Therefore the practical aspects of a musical notation that musicians may have dealt with may have been obscured by the poetic nature of the text.

After the Natya Shastra, the next major milestone in the development of Indian music is the Brihaddeshi of Matang (circa 6th century CE – 8th century CE). It is been said that this is the first text to use a notation based upon the present sargam (Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India 2021).

Moving on, the next major text in the history of Indian music is the Sangeet Ratnakar. It is a musical treatise written around the 13th century by Sharangdev. It is replete with musical examples.

Period of Islamic Rule – For the purpose of this webpage we will define this period as running from the 13th century to 1858.

This was a very rich period for the development of North Indian music; however it was marked by a musical culture which had a strong antipathy towards written music. A friend once described the mindset as, “I obtained these compositions from my Ustad only after years of service. Why should I write them down where anyone could just come and steal them from me?” Although the world view of musicians was generally hostile to the concept of musical notation, it is certain that many musicians kept notes for their own benefit.

It would not be fair to totally dismiss this period from our discussion, for there were significant examples of musical scholarship. For instance the Ain-i-Akbari of Abu l-Fazl Allami, contains numerous references to musical instruments and music of the period (Blochmann 1989). There was also the Lahjat – i -Sikhandar Shahi, written in Arabic at the order of Sikhandar Lodi. These are just a few examples of musical scholarship. Nevertheless, I feel that this period does not give us anything significant from the standpoint of musical notation.

Notations, Notations, and More Notations (1858 – 1920) – We are defining this period with two important events. 1858 marks the end of the Uprising of 1857. 1920 marks the first year of publication of Bhatkhande’s Kramik Pustak Malika, a work which revolutionised musical scholarship in Northern India.

November 1st, 1858 is a date that marks the beginning of a seismic shift in the culture of Northern India. It is on this date that the Crown took over all of the East India Company’s holdings in India. At this point India was effectively part of the British empire.

The musical culture changed because the sources of patronage changed. The suppression of the Uprising decimated the traditional sources of patronage for Indian musicians. This forced musicians to seek patronage from the wealthy Indian bourgeoisie that were rising around the British. Under this powerful cultural influence, it was inevitable that Western approaches to music would infiltrate the musical culture of North India. This was to be seen in every aspect of North Indian music.

One of the areas where this shift in musical culture was seen was in the sudden surge in books written about music. But this itself proved problematic because there was no standard approach to musical notation. Although notation had existed in some form for millennia, these early systems were woefully inadequate for the level of precision that was now demanded. It was left to each individual author to develop their own system.

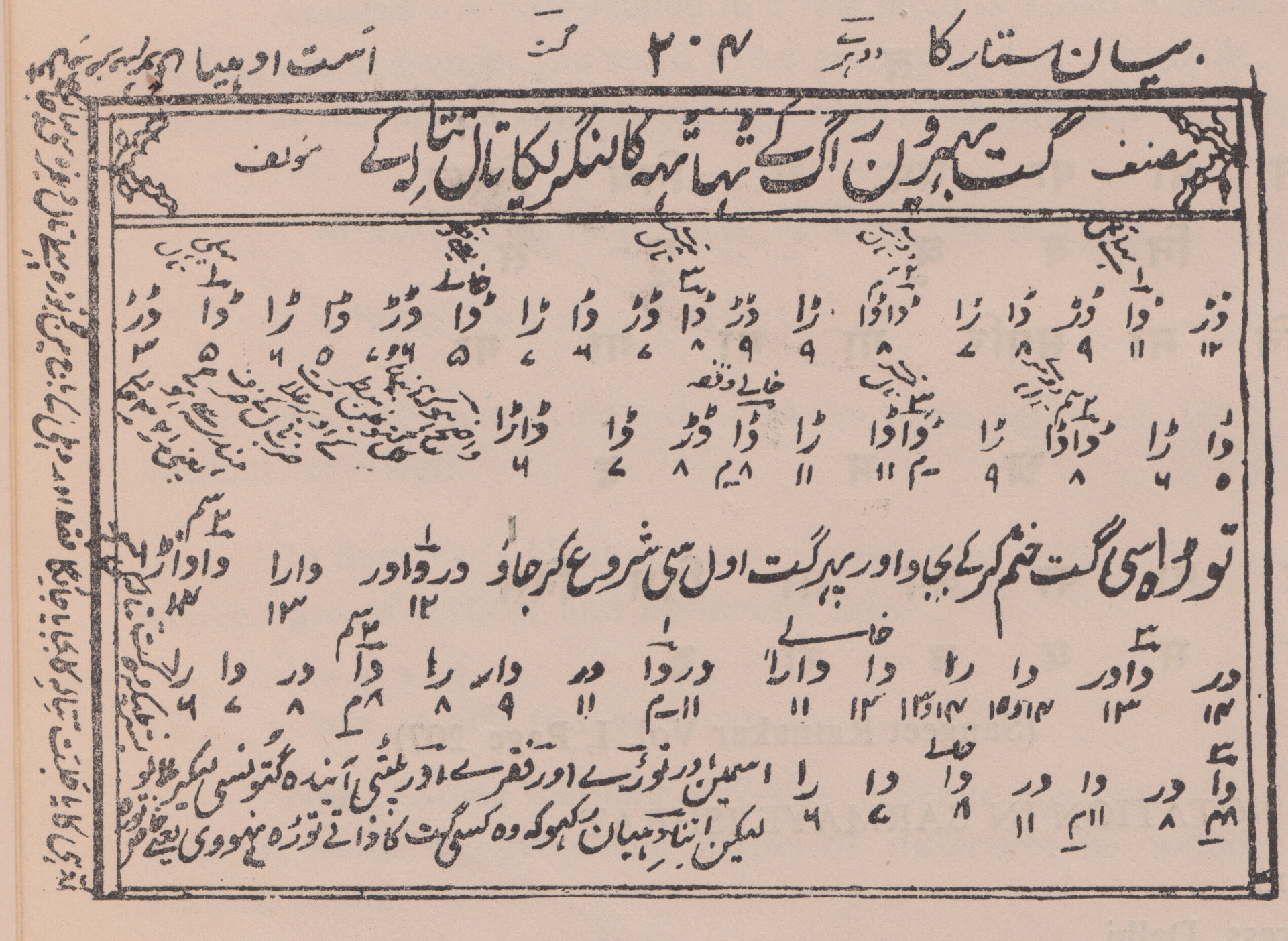

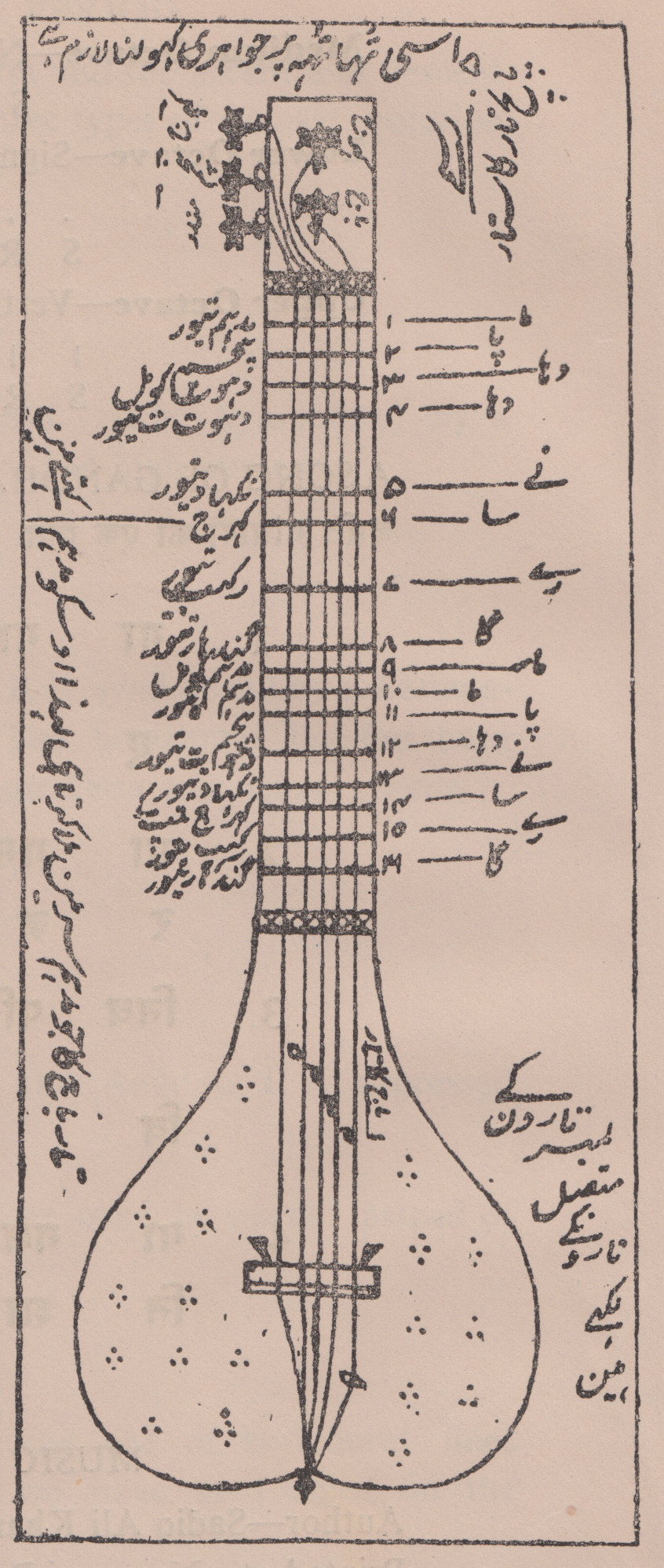

One system was put forth in the 1874 publication of Sarmaye Ishrat. This work was written by Sadiq Ali Khan in Urdu. It is a book of sitar music, and consequently it uses the frets of the sitar as the basis for the notation.

The approach of the Sarmaye Ishrat proved to be very effective and surprisingly intuitive. It served as an inspiration for subsequent authors such as Mirza Rahimbegh Khan for his 1891 publication of Naghma-e-Sitar and Tehsil ul-Sitar (Veer, 1978).

These notational systems worked acceptably for sitar, but they did not really suit the need for a more general approach to musical notation. Something considerably more flexible was required for vocal music. One very influential attempt was put forth by Pannalal Goswami in his 1896 publication Nad Vinod Granth. I am a bit unsure as to its exact publication history, but it seems that it was originally published in Urdu, but with subsequent editions in Hindi. This notational system was based upon the sargam (i.e., Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, etc) with marks above them to indicate the duration.

The first modern general purpose musical notation was developed by Vishnu Digambar Paluskar. He created this at the turn of the 20th century. As in previous musical notations, Paluskar used the sargam as the basis for a notation. But unlike many previous systems, Paluskar was particular that the rhythmic duration should be precisely specified. This was something that his notation had in common with Pannalal Goswami’s system.

It isn’t clear what inspired Paluskar to be so particular about specifying the durations of the notes. A student of Paluskar, B.R. Deodhar writes in his book Pillars of Indian Music, that this aspect of notation was inspired by Paluskar’s introduction to Western staff notation. He acquired this knowledge after meeting with a band leader named James, whom he met in a trip to Jodhpur (Deodhar 1993).

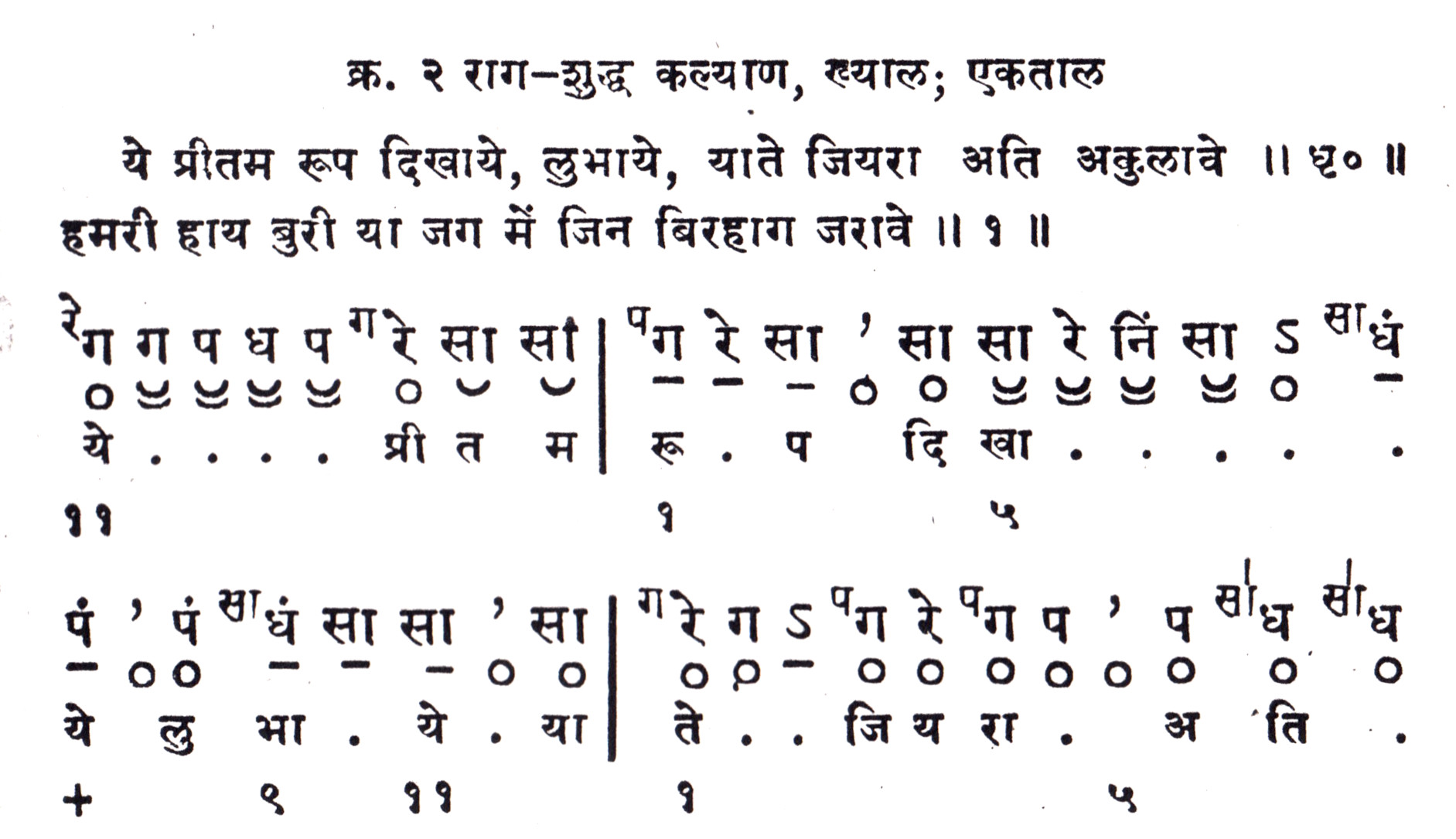

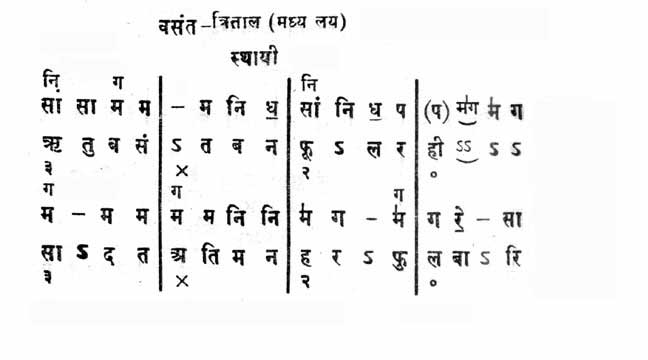

An example of Paluskar’s notation is shown below:

The Paluskar system was merely one of several systems put forth at the turn of the 20th century. Many books came out on Indian music; each of these used a notational system that was put together on an ad hoc basis. Paluskar’s notational system would have been just another one had it not been for one simple thing. He backed it up by the creation of music colleges. He created the first Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in Lahore in 1901 and then a second branch in Bombay in 1908. During the early years of the 20th century numerous music students came out of these schools, all of them familiar with the Paluskar system of notation.

The Paluskar system dominated Indian musical scholarship for many years. It was very precise, and it met the needs of both music lovers, practising musicians, and scholars, in a way that no other system had been able to before. But in the second quarter of the 20th century it began to wane, by the third quarter it was becoming rare, and by the end of the 20th century it was virtually non-existent.

Why did the Paluskar system disappear? The answer to this question can be summed up in a single word – “Bhatkhande”.

Bhatkhande’s Notation

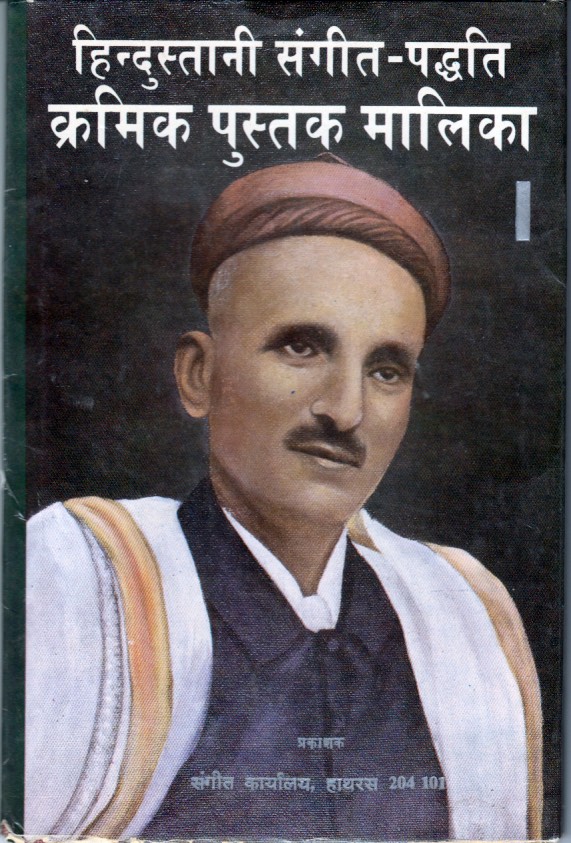

Paluskar’s system was precise, but it was difficult. It was replaced with an equally precise system, but one which was more intuitive. This system was introduced by Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande. Today it is his system which is the standard.

The Bhatkhande system was used in the publication of the first volume of Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati. The first volume of this magnum opus appeared in 1920.

Bhatkhande’s system retained the effective elements of earlier systems, but made changes in other areas, which greatly improved musical notation. One element that was retained from earlier systems was the use of the sargam as a basis for the notation. But its most revolutionary approach was in the handling of the rhythm. Paluskar’s system, as well as some earlier forms of notation, specified the duration of each note. This may have been precise, but it was very cluttered and not intuitive. In contrast, Bhatkhande shoe-horned every element into the matra (beat). This approach yielded a notation that was uncluttered and intuitive.

There only seems to be one area where the Paluskar notation had an advantage over the Bhatkhande notation. One occasionally finds tals which have fractional numbers of beats. Two examples are Rupam tal of 81/2 matras and Kalavati tal of 91/2 matras. In such situations the Bhatkhande notation becomes very awkward. However such situations are very rare, so it does not create too many inconveniences.

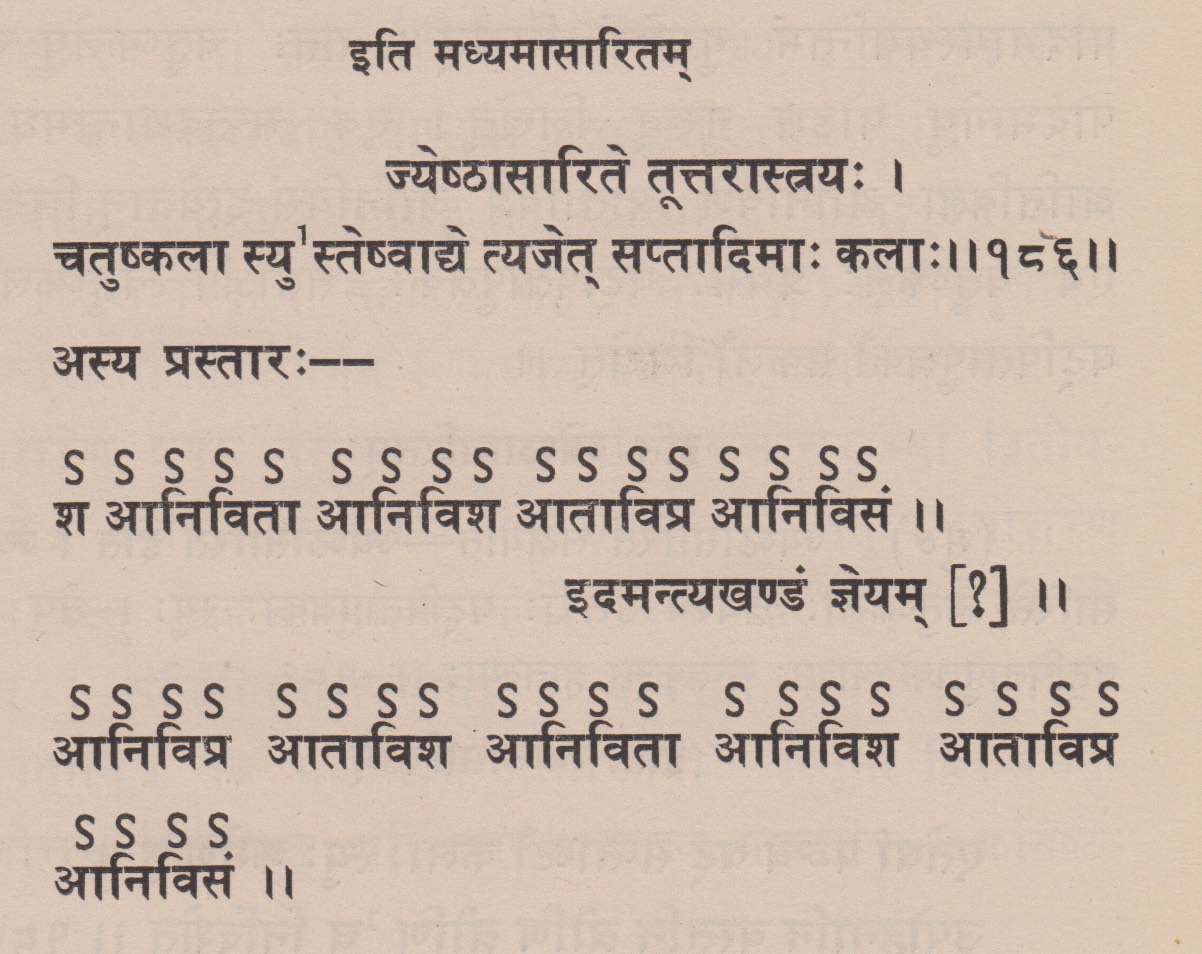

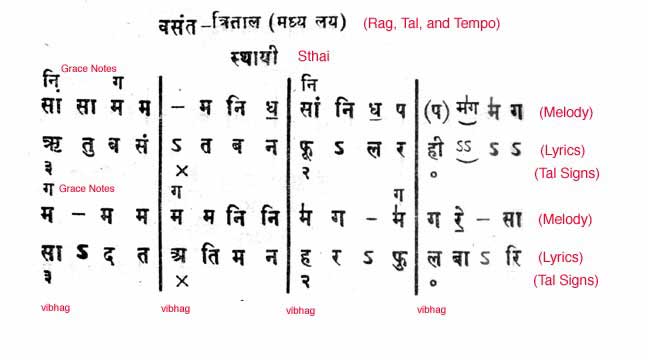

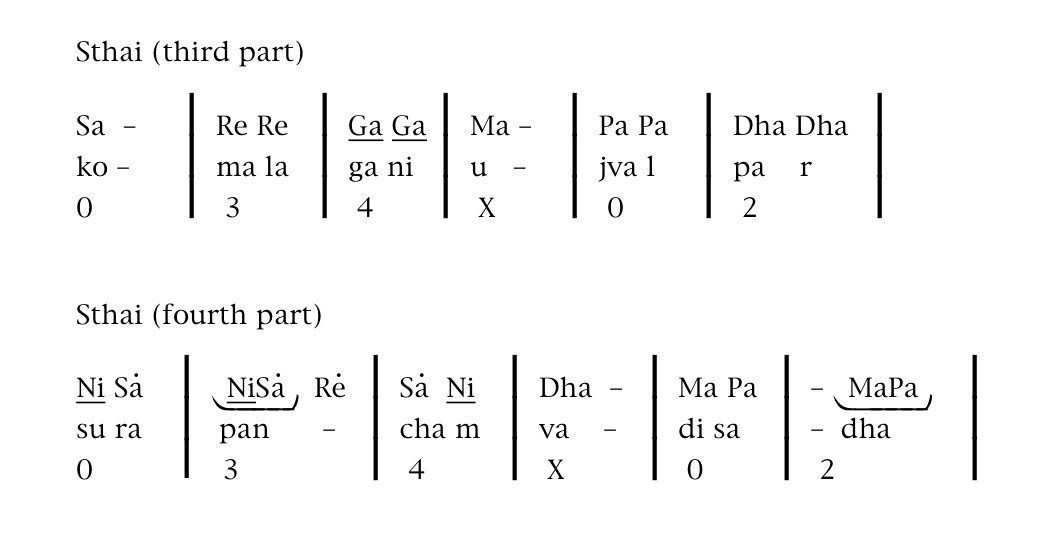

Basics of Bhatkhande Notation – Let us become familiar with the particulars of Bhatkhande’s notational system. The previous example is re-shown below with annotations to make it easier to follow:

The above example was taken from Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati – Kramak Pustak Malika: Volume 4 (Bhatkhande, 2001). This particular edition was in Hindi, consequently the script of the notation is in Devnagri. However the Bhatkhande system does not specify a script, therefore it can be written in anything.

This example shows two lines of a sthai in rag Basant. We see that there is a melody line with the corresponding lyrics underneath. This particular example is in Teental so the four vibhags are delineated with vertical lines. The clapping arrangement is designated by the numbers underneath each line. (Some authors place these symbols at the top.) There are also occasional grace notes (kan swar)which may be indicated. In the previous example there are the grace notes Ni and Ga above the 13th and 15th matra.

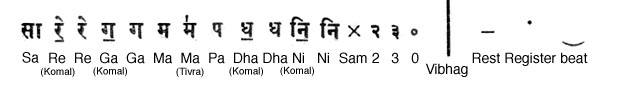

The Bhatkhande system is a model of elegance and simplicity. The basic notational elements are shown in the figure below:

In the above table we see that one simply has to write out the Sa, Re, Ga, etc. The komal swar (flattened notes) are designated with a horizontal bar beneath. The only note which may be sharpened is the Ma, this is designated with a vertical line over it. The various claps of the tal are designated with their appropriate number, the khali is designated with a zero. The sam is designated with an “X”. The vibhag is just a vertical line. A rest is indicated with a dash. The register is indicated by placing dots either above or below the swar. Finally, fractional beats (matras) are indicated by a crescent beneath the notes.

Although Devnagri is the most common script, it is not specified in Bhatkhande notation. One often finds Roman, Kannada, or a variety of scripts used. This makes it very well suited for the regionalisation and internationalisation of the musical notation.

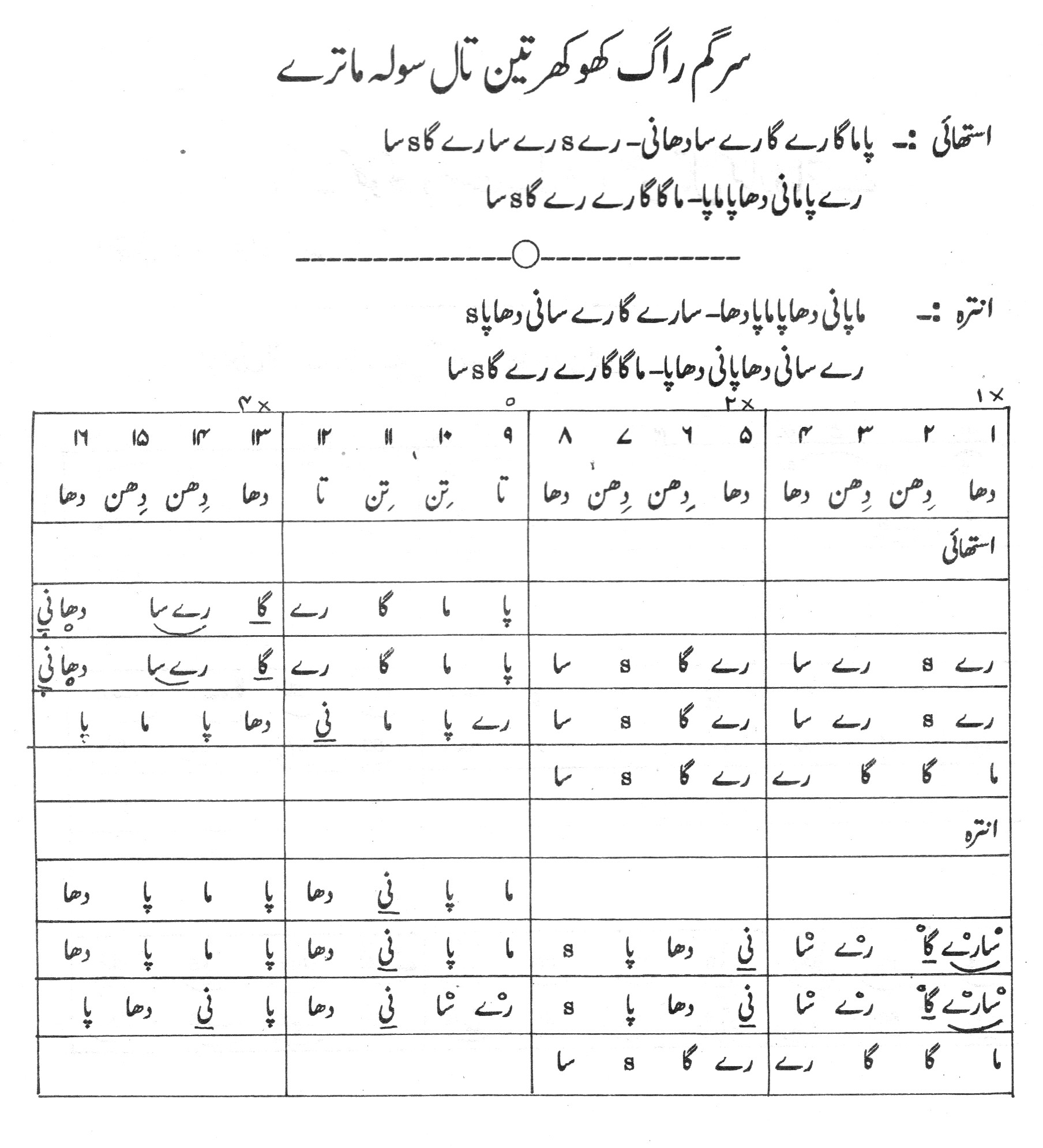

One noteworthy adaptation of Bhatkhande notation is to be found in the 1998 publication of Rag Swaroop by Ustad Mahfooz Khokhar in Pakistan. An example is shown below:

This notation is a straightforward implementation of Bhatkhande notation in the Urdu language. Because it is in Urdu, it moves from right to left instead of Bhatkhande’s original left to right. The top most line (within the blocks) contains the numbers 1-16 to designate the sixteen matras of Teental. Immediately below that are the tabla bols for Teental. These are very nice pedagogical considerations, but not strictly part of the notational system. Subsequent blocks show the sargam with the usual Bhatkhande elements.

There is one remarkable departure from the Bhatkhande system. In this approach, every clap, not just the sam, is indicated with an “X”. Therefore the clapping arrangement of Teental becomes “X1. . . X2 . . . 0 . . . X3 . . .” For a beginning student, this is far more intuitive than Bhatkhande’s “X . . . 2 . . . 0 . . . 3 . . . “

Musical Notation and the Internationalisation of North Indian Music

There are several overall approaches to the internationalisation of North Indian music notation. One approach is to translate everything into staff notation. Another is to use a Bhatkhande notation, but shift the script to Roman script. A third approach is to modify a Roman script Bhatkhande notation in way to accommodate limitations in electronic media; this is based upon the use of upper and lower case letters to indicate which position the movable notes occupy. (This last approach will be discussed in a separate section dealing with electronic media.)

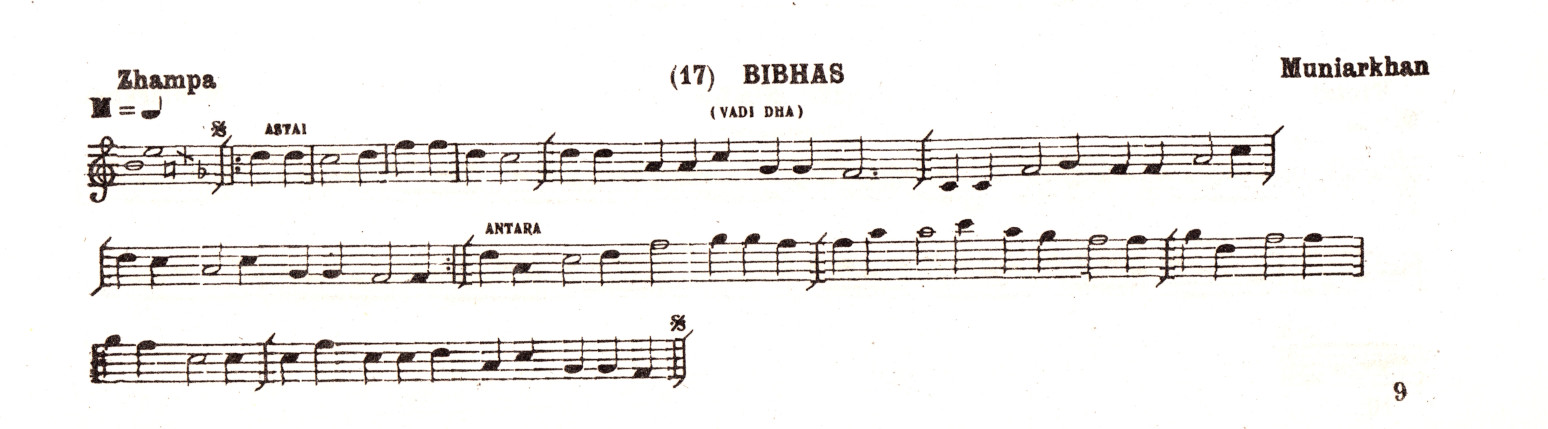

Staff notation is often used for Indian music, but it is a very controversial issue. It is true that staff notation has the widest acceptance outside of India. This is no doubt a major advantage. An example is shown below:

Unfortunately, the use of staff notation distorts the music by implying things that were never meant to be implied. When a notational system conveys wrong information, this can be just as bad as the inability to convey important information.

The biggest false implication of staff notation is the key. Western staff notation inherently ties the music to a particular key. This is something that has never been part of Indian music. In India, the key is merely a question of personal convenience. Material is routinely transposed up and down to whatever the musician finds comfortable. Over the years a convention of transposing all material to the key of C has been adopted; unfortunately, this convention is usually not understood by the casual reader. Furthermore, this convention is not always adhered to, especially by Western authors.

One other false implication is that of equal-temperament. This clearly is not implied in Indian music.

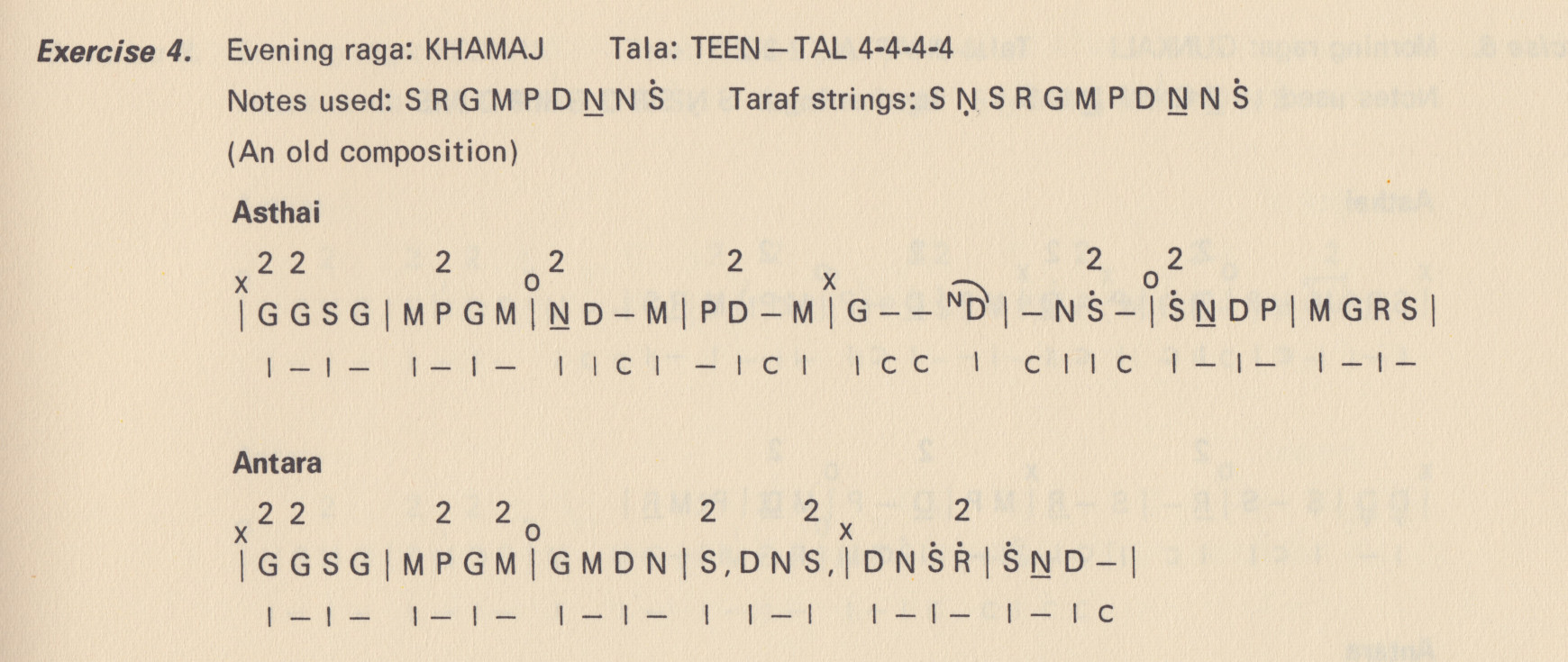

Staff notation is not the only approach to the internationalisation of North Indian music, simply writing a Bhatkhande notation in Roman script is the another approach. One example is shown below:

This is a straight-foward use of the Roman script for a standard Bhatkhande notation; but there are additional elements to specify sitar techniques. Bhatkhande’s approach does not preclude any such additions. However there is one thing which is a significant deviation. One will notice that the second and third claps of Teental are not specified, instead they are merely implied by the vibhag structure. Furthermore, the “2” has been hijacked to serve as a notational element for the sitar technique.

The biggest advantage of writing Bhatkhande notation in Roman script is that it does not distort the original material. Since Bhatkhande’s notation was never actually tied to any particular script, it is arguable that this is really no change at all. The widespread acceptance of Roman script, even in India, means that it has a wide acceptance.

However, the use of Roman script / Bhatkhande notation is not without its deficiencies. The biggest problem is that it still requires a firm understanding of the structure and theory of North Indian music. The practical realities of international book distribution and more especially the Internet, mean that information should be instantaneously accessible. One should not expect a casual visitor to a website, or a musician browsing through a music book, to invest the energy required to master the Bhatkhande notation.

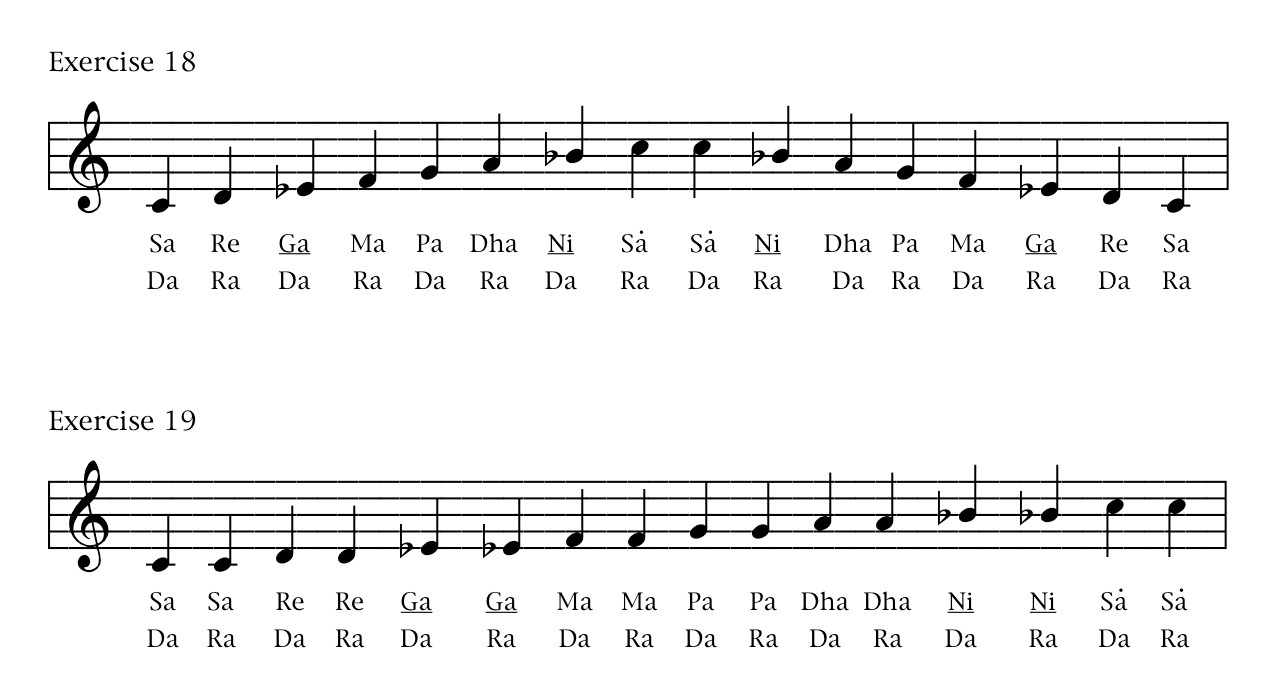

Another easy way to promote the internationalisation of North Indian music is with a combined notation. An example of some basic exercises of rag Kafi in a combined notation is shown below:

This notation has all of the clarity of Bhatkhande notation, as well as the accessibility of staff notation.

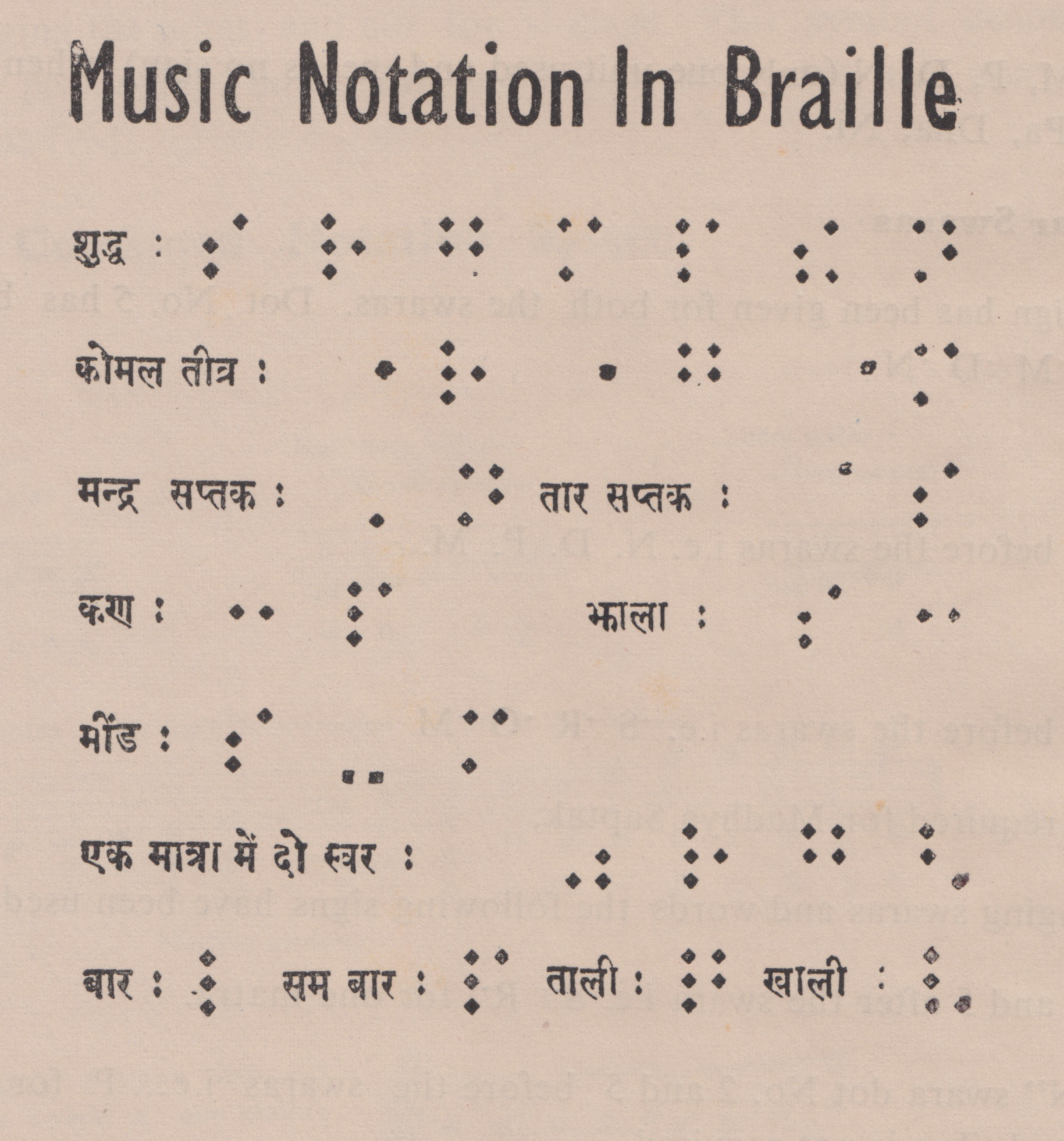

Indian Musical Notation in Braille

There are options for Indian music notation for the blind (Veer 1978).

Indian Notation and the Electronic Media

The introduction of word processors and the advent of the Internet have exerted a tremendous influence over the development of North Indian musical notation. This is because the Bhatkhande notation is not directly supported by any of the standard encoding schemes.

In the present computing environment, one is forced to make certain modifications in one’s approach. People have to choose whether to modify the software to accommodate the notation, or to modify the notation to accommodate the limitations of computers. Both approaches are in use.

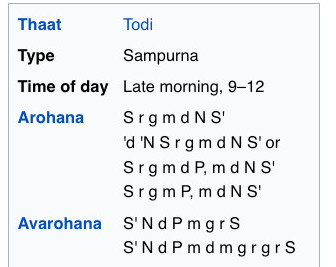

Modifying the Notation – One popular approach modifies the way in which the sargam is specified. Here is portion of an example from a Wikipedia article on Rag Todi (Wikipedia 2021).

Let us make a few observations about this notational system. To begin with, it is based upon the sargam, as most Indian systems are. However it uses a different way to describe the alternative forms of notes. This is described in the table below:

| S | r | R | g | G | m | M | P | d | D | n | N | S’ |

| Sa | Komal Re | Shuddha Re | Komal Ga | Shuddha Ga | Shuddha Ma | Tivra Ma | Pa | Komal Dha | Shuddha Dha | Komal Ni | Shuddha Ni | Sa |

This notational system was adopted by the Ali Akbar College of Music in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was convenient because it allowed anyone with a typewriter to write Indian music with great precision. This college turned out numerous students who were influential in the use of the Internet for the propagation of Indian music. Consequently it is a very common approach to dealing with North Indian music on the Internet.

This form of notation had its origins in the state of the technology half a century ago. If you were banging away at a typewriter in Northern California in the pre-Internet days, there were very good reasons to use this notation.

Today, its raison d’etre is gone. There is no reason to continue using this system other than laziness or ignorance of established conventions.

Minimal Modification – It is possible to implement a standard notation with only minimal adjustments. The present Unicode standard supports an almost unthinkable number of glyphs, many can be used to approximate a standard Bhatkhande notation. The table below is more consistent with traditional notation, yet is still compatible with almost all digital platforms:

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Sa’ |

| Sa | Komal Re | Shuddha Re | Komal Ga | Shuddha Ga | Shuddha Ma | Tivra Ma | Pa | Komal Dha | Shuddha Dha | Komal Ni | Shuddha Ni | Sa |

Modifying the Software – It is possible to completely accommodate a standard notation by modifying the software. Although Indian musical notation is not directly supported by current environment, this can be changed.

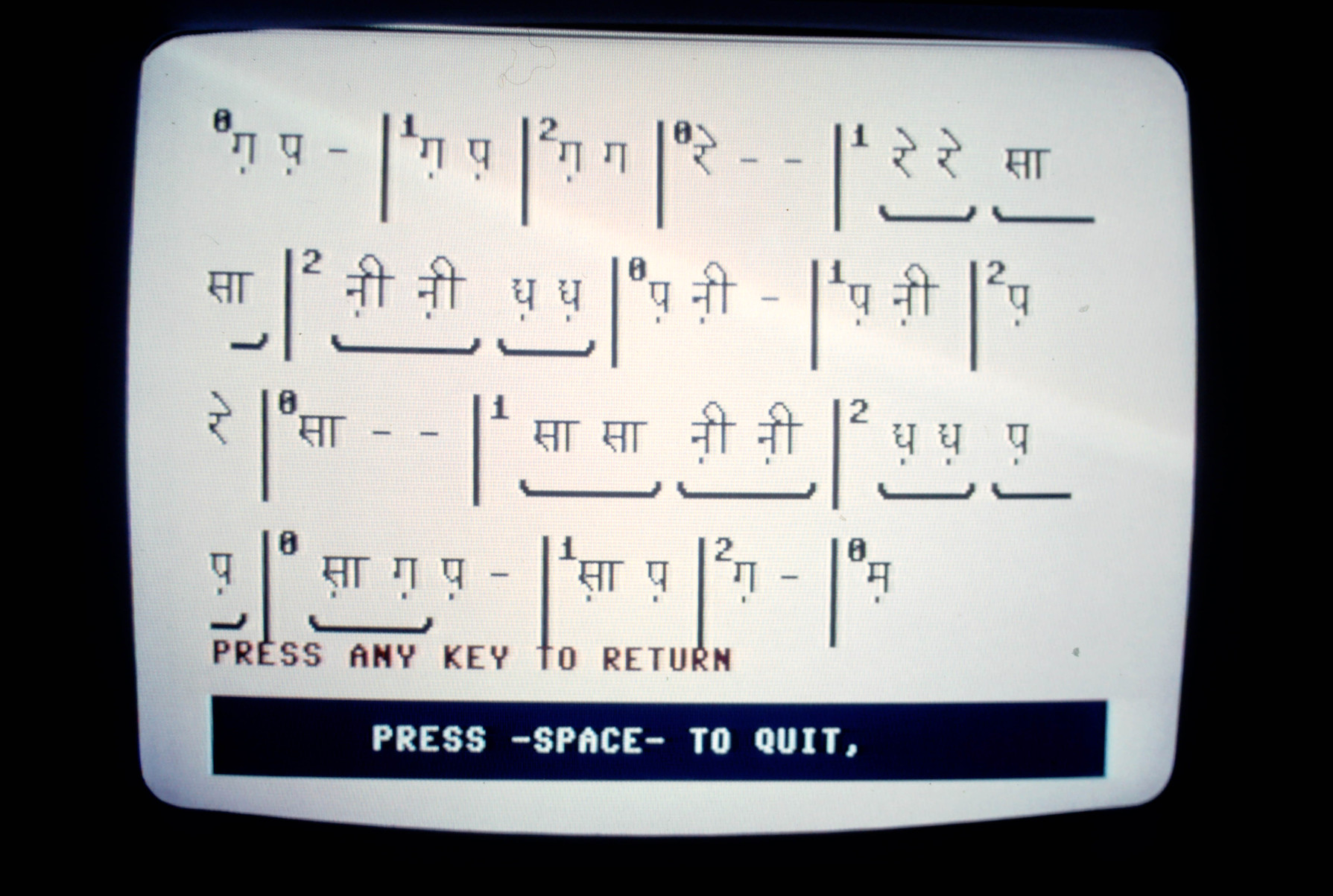

The modification of a computer’s software to support traditional Indian notation is not new. It predates the widespread use of the Internet by a number of years. One system was in use as early as 1987 (Indian Express 1987). This could handle an audio output as well as a simultaneous display of the notation in a Bhatkhande format (United News of India 1987). Below is an implementation of a Devnagri / Bhatkhande notation on a vintage 8-bit computer (Courtney 1991).

These early endeavours were far more difficult than what is required today. They required an extensive reworking of the operating system. However the modular approach of modern operating systems makes things easier. Below is a sample of text that was made with a standard word processor with no more than the alteration of a few characters in the font (Courtney 2015) :

SVG – There is another approach to the handling of North Indian musical notation; this is in SVG. SVG is an abbreviation for “Scalable Vector Graphics”. This approach is philosophically similar to the redefinition of characters in a font. However for Internet based applications, it has the advantage that it does not require the user to download a custom font set.

Unicode – The ultimate solution will undoubtedly be in the Unicode system. This is a continuously evolving system of encoding characters from around the world. The majority of the elements are already in place, but significant holes exist. Until such a day when these holes are filled, we will be forced to other means to implement a notation.

Notation Software – The ideal situation would be a complete coverage of North Indian musical notation by the Unicode standard; but until this happens there is software to handle this. The various low level hacks that we have alluded to need not be done by the casual user, because software is available from programmers who have already done this.

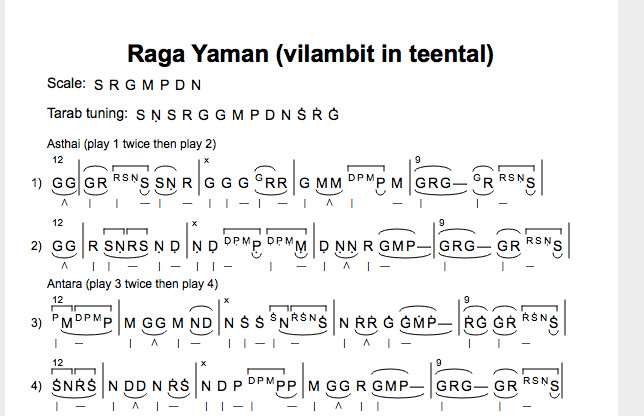

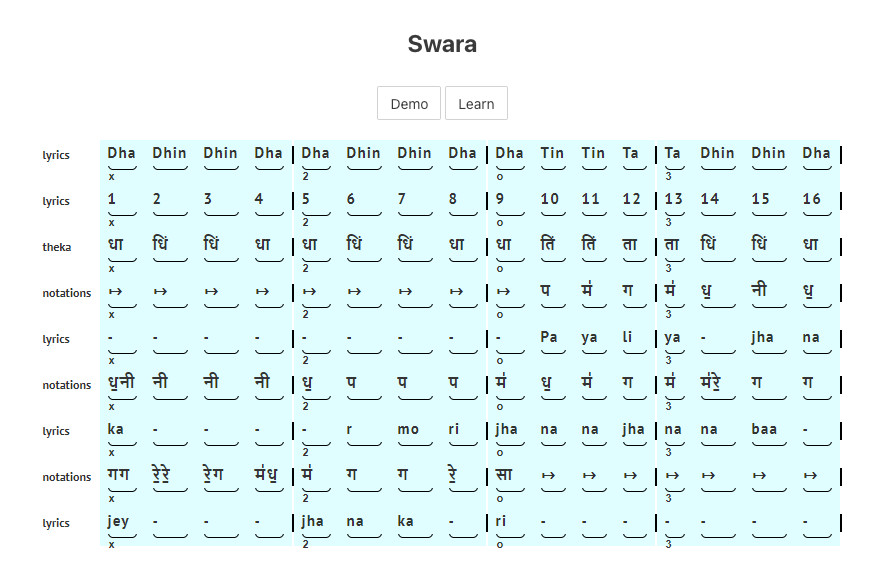

One example is “Sargam”. This is an open source software that works on both Mac as well as PC. It allows the user to type in a detailed notation of Indian music without having to do the programming themselves. It works in both Roman script as well as Devnagri. An example is shown below:

Another software package for the notation of Indian music is “Vishwamohini”. Below is a sample taken from their website:

These systems are still in the developmental stage. But they offer tremendous possibilities and hope for the future.

Conclusion

The notation of Indian music is arguably one of the longest running “work in progress” that the world has seen. Perhaps it is just in the nature of things that it will never truly be worked out. I just hope that this modest survey of the subject will inspire someone else to take it up and perhaps iron out the last few wrinkles.

Selected Video

Works Cited

Bharatamuni – Sri Satguru Publications (translators)

undated – The Natya Shastra. (Translated by a Board of Scholars), Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications.

Bhatkhande, Vishnu Narayan

1993 Hindustani Sangeet – Paddhati (Vol 1 ): Kramik Pustak Malika. Hathras: Sangeet Karyalaya.

2001 “Vasant – Trital (Madhya Lay)” Hindustani Sangeet – Paddhati (Vol 4 ): Kramik Pustak Malika. Hathras: Sangeet Karyalaya.

Blockmann, H. (translator) Abu l-Fazl Allami (author)

Circa 1590 Ain-i Akbari. Translated by H. Blockmann. Delh: 1989. Reprinted by New Taj Office.

Courtney, David R.

1991 “The Application of the C=64 to Indian Music: A Review”, Syntax. June/July: pp. 8-9: Houston.

Courtney, David R. and Chandrakantha Courtney

2015 Elementary North Indian Vocal: Vol. 1. Houston: Sur Sangeet Services.

Courtney, David R. & Srinivas Koumounduri

2016 Learning the Sitar. Pacific MO: Mel Bay Publications.

Deodhar, B.R.

1993 Pillars of Hindustani Music. Translated by Ram Deshmukh. Bombay: Popular Prakashan Pvt. Ltd.

Express News Service

1987 “Raga Recording on Computer”. Indian Express. Wed, Nov. 18, 1987. Hyderabad: Indian Express.

Garg, Balakrishna (editor)

1976 Brihaddeshi. Hathras, India: Sangeet Karyalaya.

India, Ministry of Culture and Broadcasting

2021 Brhddsi Sri Matanga. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. http://ignca.gov.in/brhaddesi-of-sri-matanga-muni/. Last updated Sept 17th, 2021. Downloaded Sept 18, 2021.

India Postal and Telegraph. Govt of India

1973 V.D. Paluskar Memorial Stamp. Govt. of India.

Khan, Sadiq Ali

1874 Sarmaye Ishrat. Delhi: Narayani Press.

Khokhar, Mahfooz

1998 Rag Swaroop. Karachi: Fareed Publishers.

Klostermaier, Klaus K.

1994 A Survey of Hinduism. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Griffith, Ralph T.H.

1896 The Hymns of the Rig Veda: Translated with a Popular Commentary. Benares: E.J. Lazarus & Co.

Patwardhan, V.N.

1947 Rag Vijnan. (Vol 4). Poona: Vinayak Narayan Patvardhan.

Puranastudy

2021- CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. (downloaded Sept. 18, 2021).

Saletore, R.N.

1985 “Vedas”, Encyclopaedia of Indian Culture (Vol. 5 V-Z), pp1562-1566. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Sastri, S. Subrahmanya, and S. Sarada (editors)

1986 Sangetratnakara of Sarangsdev (vol 3). Madras: Adyar Library and Research Centre.

Shankar, Ravi

1968 Ravi Shankar: My Music, My Life. New Delhi, India: Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd.

Sri Satguru Publications

1986 “Bibhas”. Encyclopaedia of Indian Music with Special Reference to the Ragas. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications.

United News of India

1987 “American Develops ‘Raga’ Processor”. NewsTime, Mon. Nov. 16, 1987, India: News Time India.

Veer, Ram Avatar

1978 History of Indian Music: Notation System. New Delhi: Pankaj Publications.

Welch, Sarah

2018 File:1500-1200 BCE, Vivaha sukta, Rigveda 10.85.1-8, Sanskrit, Devanagari, manuscript page.jpg. Uploaded by Sarah Welch.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1500-1200_BCE,_Vivaha_sukta,_Rigveda_10.85.1-8,_Sanskrit,_Devanagari,_manuscript_page.jpg Downloaded Sept 3, 2021.

Sargam Software

2021 https://sargamdev.wordpress.com/ Downloaded Oct 3, 2021

Vishwamohini Software

2021 http://vishwamohini.com/music/home.php, Downloaded Oct 3, 2021

Wikimedia Commons

2009 Brahmi pillar inscription in Sarnath. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d8/Brahmi_pillar_inscription_in_Sarnath.jpg. Downloaded Sept 10, 2021.

Wikipedia

2021 “Todi (Raga)”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Todi_(raga). Wikipedia. (screen capture Sept 23, 2021).

Other Sites of Interest

Music-cultures in Contact Convergences and Collisions

The Turning Point in Indian Music Pt. Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande

Brief Contribution: An Eighteenth Century Notation of Indian Music