The Folksong of Northern Bangladesh

by Wing Commander Mir Ali Akhtar (Retired)

and

David Courtney ![]()

| Vaoaiya (Bhawaia): The Folksong of Northern Bangladesh Part 1 – Introduction Part 2 – Music and Texts Part 3 – Glossary, Misc., Works Cited |

Bangladesh has a rich tradition of folk music. Although internationally the Baul music is the most well known, there is also the vaoaiya (bhawaia), jari, shari, bhatiyali, jager-gaan, jhumur-gaan, shoitto-peerer-gaan, gajir-gaan, gomvira, baul-gaan, jhapan-gaan, maijvandari-gaan, jogeer-gaan, marfoti-gaan, murshidi-gaan, alkap-gaan, torja-gaan, ghatur-gaan, letor-gaan, dhuaa-gaan, khapa-gaan, and a host of others. This page will concentrate on the vaoaiya(a.k.a. Bhawaia), which is one of the most popular mainstream folk-songs of northern Bangladesh.

Background

The history of the vaoaiya folk song, like the history of most folk arts, is not always clear. It is believed that the vaoaiya originated in the Rangpur Districts and the Koch Behar. Many believe that it is traceable back to the 14th and 15th century.

The first scholarly approach to the subject of vaoaiya appears to be the work of Sir Abraham Grierson (1851-1941). He was a former British Deputy Collector of the Rangpur district. He collected two vaoaiya lyrics 1898 and used them as an example of the local dialect. It is published in his book Linguistic Survey of India (1903), Vol-V, Part-I.

Etymology

The term “vaoaiya” is of uncertain origin. Due to varying pronunciations, it is also often transliterated as “Bhawaia”. When one looks at the history of the usage of word, as well as the history of the folk-song, many inconsistencies are seen.

Several different etymologies have been proposed. It has been suggested by late Shibendro Narayan Mondol of Goripur Assam, that the term vaoaiya is derived from the term “bhava” which means emotion. This is consistent with the themes of love which are the predominant emotion of this folk-song. However a somewhat different view was put forward by the Late Dormonarayan Voktishashtree of Kaligonj, Lalmonirhat, Rangpur. He suggests that term “vaoaiya” originated from the term “vabaiya” means “that which inspires contemplation”.

These two etymologies may not be as conflicting as they might on the surface appear. It is certainly possible that there is a linguistic link between the Sanskrit “bhava” and the vernacular “vabaiya”. If so then, both etymologies may be considered to be somewhat related.

The usage of the term “vaoaiya ” is not universally accepted. If one goes to very isolated areas, people may sing the vaoaiya folk-song, but are unaware of the term. (1999/Boidder bazaar; 2003, Roumari). Even as late as 1903 in Sir Abraham Grierson in his Linguistic Survey of India, he uses some well known vaoaiya lyrics to illustrate dialects of the area, but does not use the term vaoaiya.

In all probability the songs have been in the region for a very long time, but the term seems to have arisen relatively recently. It appears that these songs were originally referred and named by its subject or main hero of the lyrics. Therefore a vaoaiya lyric about trapped crane (boga) was famous as bogar-gaan (song about he crane), another vaoaiya about (bull-cart driver) would be called gaariaal vai. A song about the chilmari river port, would be called chilmarir-gaan. such designations are still used by folk musicians today. However sometime between 1887 and 1903 the term “vaoaiya” came into usage.

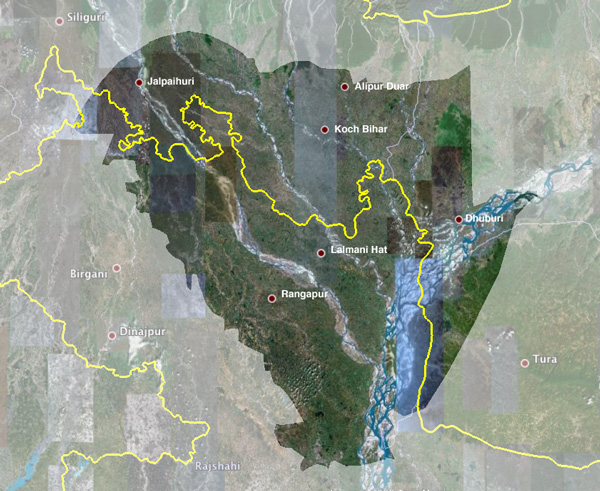

Geographical Distribution

The geographical distribution of the vaoaiya folk song covers much of the Rangpuri (dialect of Bengali) speaking areas of northern Bangladesh. Precisely vaoaiya is the mainstream folk-song of the Dhorla, Dhudhkumar, Tista, Brahmaputtra river basin area. The vaoaiya is also found in the Koch Behar, Jalpaiguri, Darjeeling (Torai), and Goalpara area of Assam where the Rangpuri/Rajbangshi dialect is also spoken.

Language and Dialect

This folk-song is sung in a rustic dialect of Bengali (a.k.a. Bangla or Banga Bhasha). The various dialects of Bengali are part of the Eastern group of Indo-European family of languages. The particular, dialect in which most vaoaiya folk-songs are found is Rangpuri, otherwise known as “Rajbongshi”. Word “Rajbongshi” is the name of a very powerful race of this once Non-Aryan land. Rajbongshi dialect was frequently called Rangpuri and derives its name from one of the Districts in which it is spoken.

In 1903 -1878 the following numbers of people used to speak in Rangpuri or Rajbongshi dialect area-wise:

- Rangpur: 2,037,460

- Cooch Behar: 562,500

- Jalpaiguri: 568,976

- Darjiling (Tarai) : 47,435

- Goalpara : 292,000

The performance of the vaoaiya uses a very stylised and exaggerated use of aspirations. These aspirations are much more pronounced than the aspirations normally found in the day-to-day dialects of Bengali. This produces a very characteristic performance style that is much appreciated by the connoisseurs of this rustic art-form. However, since the use of these exaggerated aspirations carries no linguistic consideration, it is better to consider this to be a musical ornamentation rather than a linguistic characteristic. As such, we will return to the topic later.

Social Settings

The vaoaiya folk-song must be seen in the context of its rural social environment. We will look at the social aspects of the vaoaiya from four standpoints. We will look at the connection with the agricultural work; the performance within the folk theatres, the instruction and propagation of the art form, and gender associations.

The most common situation in which this folk-song will be performed is within the context of agricultural labour. These songs are commonly sung while farmers are at work, during breaks, and to relieve the monotony and loneliness at night when they are off in the fields, or otherwise away from home. These working class villagers are always on the move due to the nature of their jobs, therefore, it is a form of entertainment that is well suited to their lifestyle.

The connection between folk-song and agricultural labour, is very strong. For instance some types of songs have completely disappeared as the particular form of labour disappeared. For instance the dolabarir-gaan (songs of low-land cultivation), vuinira-gaan (weed-picking songs), gatar-gaan (songs of communal cultivation), have completely disappeared as these particular jobs disappeared.

This folk song may be closely associated with labour, however in the not too distant past, the vaoaiya broke out of its traditional agricultural setting and found a new home in the folk theatre. It became very important for three types of theatre. These were the kushan, dotora-gaan and poddopuran. Of these three dotora-gaan is no longer extant.

There is a new setting which is beginning to emerge. Due to a renaissance in Bengali culture, urban dwellers are now beginning to attend concerts and performances of folk music. Today the vaoaiya and other Bengali folk music may be seen and heard on stages and in theatres in the cities.

There are a number of positive aspects of this new form of consumption of the art. There has been the positive effect of giving traditional folk musicians additional sources of income. It serves to preserve forms of folk-song that might disappear due to changing social, agricultural, and economic conditions in the villages. It also raises the awareness of folk art-forms in areas outside of the districts where they have traditionally been performed. However we must also remember that taking the folk music outside of its traditional environment begins to alter its fundamental nature. For the same reason that zoos are not a substitute for preservation of natural wildlife, in the same way, the rise in popularity of folk theatre in non-traditional; urban settings is not a panacea for the loss of rural cultures.

For any art-form to thrive, there must also be a vibrant system for its instruction and propagation. The instruction for the vaoaiya folk-song is typical of instruction of folk music throughout South Asia. It is strictly an oral tradition. However unlike the formalised systems of training which are typical of the classical traditions, (e.g. Hindustani Sangeet), this oral tradition is significantly less formalised. As such, you occasionally find material transmitted from teacher to student within the confines of a moderately structured theatre group, but it is more likely that the folk-songs are simply absorbed organically in the same way that other aspects of culture (e.g., food, languages, religious beliefs) are transmitted. It should be mentioned that institutional presence in the preservation, and transmission of folk-songs is presently underway, both by governmental organisations as well as NGOs, but this is still in its infancy.

There are strong gender associations in the vaoaiya. Although the themes of the songs often were those of the feelings of women, the vaoaiya were usually composed and performed by men. It is interesting to look at this fact from the standpoint of women’s rights. Where the urban Bengali male only became vocal concerning women’s rights after mid 20th century, the performers and composers of this folk-song were showing these same concerns at least a century or two earlier. In someway those folks may be considered to be pioneers in this movement. Can this be considered to be a proto-feminist movement?

It must be noted that simply being concerned about the condition of women is not the same as the empowerment of women. The fact that women originally did not sing the vaoaiya, does raise questions about it feminist credentials. However in recent years, there has been a rise in of feminist school of thought which actively embrace the concept of essentialism. The non-participation of women in the performance of the vaoaiya may be merely a rural acknowledgement of this basic essentialism, specifically in regards to the division of labour. With the ever widening definitions and scope of feminism, it is arguable that the traditional vaoaiya may have elements of essentialist feminist thought.

Ultimately these discussions of whether vaoaiya may be considered to represent a form of essentialist based feminism is of absolutely no importance for several reasons. First, I believe that most people would praise the efforts and sentiments of the pro-women stance, but would balk at its inclusion into the relatively narrow definitions of feminism. Secondly it is a mere academic exercise attempting to force an element of Bengali folk culture into a largely irrelevant Western intellectual cubby-hole. Finally, the conditions have totally changed since the 1950’s. From that time on, women have been singing and performing the vaoaiya; therefore the non-participation of women has been a non-issue for half a century.

The social settings are certainly important for the production and consumption of this art-form, but this naturally leads us to some other topics. We have already alluded to the fact that these settings are reflected in the subject matter of the songs. It is therefore appropriate for us to take a much closer look at the themes and subject matter of these songs.

Themes and Texts

The themes of the vaoaiya folk-song reflect the experiences of rural life in northern Bangladesh. They reflect the professions and viewpoints of village life. We can say that the themes of this folk-song revolve around four main topics. These deal with occupations, common life issues, nature, and folk journalism. Although a review of the agrarian lifestyle readily shows that all of these topics are interrelated, it never-the-less forms a convenient position from which to begin our discussion.

The vaoaiya is commonly linked to the professions of rural life. Common professions are the, mahout (elephant handler), moishal (buffalo handler), rakhal (cow boy), boidals (bull cart driver), garials (cow cart driver) hallooa (cultivator), or the vui-nira (weed cleaner of the crop fields). The varied aspects of these professions form major themes for the folksongs.

However, the themes of the various professions do not stay confined to professional topics, for they spill over into the area of lifestyle and life issues. Evening often finds the villagers many miles away from their homes. For instance, in the old days, moishals (buffalo handlers) had to stay in bathans away from home and family. Mahoot (elephant drivers) too, worked in the distant riverbank areas and forests, had the same hard and lonely fate. Garial (cow-cart drivers) had to transport rice, jute etc. to distant ports or market places; such trips often took several days. The separation imposed by the nature of the agrarian economies naturally lead to feelings of loneliness. It should be no surprise that such feelings are commonly reflected in the themes of the vaoaiya folk-song.

Common life-issue subjects of vaoaiya are men-women’s worldly affection, spiritualism, desire of affection, painful feelings of lost love, destitution, desire of pre-marital meetings, sufferings of early widowhood, late marriage of mature women, etc. It also reflects women’s variegated feelings such as love, affection, likes, dislikes, hopes, frustrations, etc.

Nature also forms important themes of the vaoaiya folk song. The nature of the agrarian existence brings people into close contact with nature; therefore birds and other animals play an important part in this art-form. Appearances of birds are especially notable in vaoaiya‘s lyrics. In fact, birds are used to symbolise women’s emotion. In vaoaiya, birds are the symbolic bearers of messages concerning their love and feelings to distant beloved ones. Rivers, and floods are also important themes of vaoaiya. This is simply because they play such an important role in shaping the rural lifestyle.

Vaoaiya is a good example of folk journalism. From its lyrics we know aeroplanes were first seen in this area (Rangpur) sky in 1931. Vaoaiya bears information regarding World War II, this is seen in references to the construction of Lalmonirhat airfield, construction of Kurigram – Chilmari railway track, and other themes. We also get information regarding natural disasters such as cyclones (hurricanes), floods, tidal-bore, famine, etc.

The fact that the vaoaiya folk song reflects themes of the pastoral existence is no surprise; however we must also take note of themes which are conspicuous by their absence. Vaoaiya was never composed on mythological characters or tales. Unlike many other folk-songs of the subcontinent, Lord Krishna and Radha have no presence in vaoaiya‘s theme. The name “Kala” (nickname of the Lord Krishna) is found in few lyrics, but that has no religious link, is only to address a women’s beloved one.

Classifications of Vaoaiya

The classification of the various forms of vaoaiya is a thorny topic. As in many other folk art forms, scholars have proposed classifications, which may be academically defensible, but are generally not acknowledged by the practitioners themselves.

Scholars have classified the vaoaiya as:

- Chitan – “Chit” means “to lie on the back”, probably they wanted to mean that a vaoaiya song which is sung in chit position may be called chitan. This classification is a bit problematic because all songs can be performed in chit or Kait (laying on ones side) position. According to this definition, musical characteristics are irrelevant.

- Khirol – This is the name of a river in West Bengal. A few scholars suggest that when the lyrics of the song refer to this river, then the song is of the khirol class. But again the musical characteristics are irrelevant.

- Kata-Khirol – This classification is somewhat problematic. This term is neither found in the dictionary, nor used by the common villagers, nor educated Bengalis. “Kata” means “cut”. I interviewed many popular vaoaiya singers concerning this term and no one could provide an example.

- Doria – The term “doria” means “sea”, but the geographical distribution of the vaoaiya is away from the sea. Therefore the meaning of this classification is not clear.

- Dighol-Nasha – “Dighol” means “long”, and “nasha” means “nose”, so “dighol nasha” would be “long nose”. But people also use the word “nashi” amongst the pile (supporting singers-cum-actors) of folk theatres for those who can sing in the high register.

- Moishali – The term “mohis” means “buffalo”. Moishali means “connected with buffalo”. Therefore moishali – vaoaiya refers to themes that refer to buffalo. Again the musical characteristics are irrelevant.

- Goran – The term “goran” means “rolling on sides”. This classification is also problematic. There is no such tune of folk-song vaoaiya which resembles somebody rolling on the sides and singing.

We must reiterate that although these classifications have been used by scholars, they are generally not used by the performers of these folk-songs. Instead one finds a system of classification based upon prominent words of the lyrics. It should be noted that the musical characteristics of these classifications are irrelevant.

Here are some examples of the forms of vaoaiya as the people themselves would classify them:

- Bogar-Gaan – There is a famous song “Fande poriya boga kande re”. “Boga” means “he-crane”, therefore “bogar-gaan” means “Song that refers to the he-crane”.

- Garialvaier-Gaan – There is a famous song, “Oki garial vai koto robo ami ponther ..” “Garial vai” means “cart driver brother” (“Vai” means “brother” and is a common term of endearment”.) Therefore, Garialvaier-Gaan means “a song which refers to the brother cart driver”.

- Chilmari-Bondorer-Gaan – A line in one famous song goes, “….. hakao gaari tiu Chilmarir bondore…” “Chilmari” is name of a famous river port of Brahmaputtra. Chilmari-Bondorer-Gaan literally means “Song that refers to the port Chilmari.”

- Kuruar-Gaan – Kunkura is kind of grass used to make fishing nets and fishing line for hooks. The bogar-gaan is also known as kunkurar-gaan, because “… ahare kunkurar suta…..” is also in the same lyrics.

- Veloar-Gaan – “Veloa re tui kene kandish ..” The term “veloa” means “an old owl”. In a famous vaoaiya, “Oh old owl, why do you cry while perched on the cottonwood branch?”. The term “veloar-Gaan” literally means, “A song that refers to an old owl”

| Vaoaiya (Bhawaia): The Folksong of Northern Bangladesh Part 1 – Introduction Part 2 – Music and Texts Part 3 – Glossary, Misc., Works Cited |