The drone is an essential part of traditional Indian music. It is found in classical music, folk music, and even many film songs. Sometimes it is provided by special instruments and instrumentalists; at other times it is provided by special parts of the melodic instruments. Even many of the percussion instruments are tuned in such a way as to reinforce the drone. Regardless of what provides the drone, it serves a vital function.

What Do We Mean By “Drone”

It is necessary to examine what we mean when we talk of a “drone”. The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music defines it as, “In musical composition, long sustained notes, usually in the lowest part….” (Randel 1978). In a similar vein, the Oxford Universal English Dictionary defines drone as, “A continued monotonous humming or buzzing sound, as that of the bass pipe of a bagpipe”, or “To give forth a continued monotonous sound” (Little, et al 1937). This definition only partly captures the character and virtually none of the significance of the drone in Indian music.

From an Indian standpoint, a much better treatment of the word “drone” is:

The drone, which is indispensable in all public performances of Indian music, provides an effective background to the melody, and adds the stability which in western compositions is furnished by harmony.

“The Story of Indian Music and its Instruments.” Rosenthal, 1928

We are faced with semantic problem with our use of the term “drone”. In the Indian context, the drone is often continuous, but often repetitive, and in many cases occurs only periodically. We would be hesitant about conflating a chord with an arpeggio, but we are forced to adopt an uncomfortably broad definition of “drone” for this webpage.

We could avoid this problem entirely by using the common Indian term for it. In India this is usually referred to as “shruti“. “Shruti” is defined as “hearing” (Apte 1995), but a musical significance implies a drone or the key. Unfortunately the Indian term has its own problems; one being a plethora of different meanings within different contexts. Even when we confine ourselves to its musical meanings, we find that “shruti” also means “microtone”. Consequently, if we used the Indian term, it would not necessarily have made things easier.

Therefore we will use the English term “drone”.

Perhaps our approach to the word may extend too much latitude for your comfort. (It certainly is uncomfortable for us.) But we are dealing with an aspect of Indian music which does not have an exact equivalent in the English language. Your indulgence in this matter is appreciated.

Function of the Drone

The function of the drone is to provide a firm harmonic base for the music. Although this may not be intuitive, it is not difficult to understand. A contrast between Indian and Western music is a good way to illustrate the drone’s function.

The tonic in Western music is implicit in the scale structure. There are amazingly few modes used in Western music, so the mind unconsciously looks at the intervals between the notes (e.g., whole-step, whole-step, half-step, etc.), and uses this structure to identify the tonic. The numerous modes used in Indian music make this process nearly impossible. Since virtually any combination of intervals may be found, it is clear that there must be another process for identifying the tonic.

It is the drone which unambiguously establishes this tonic. The continuous, or at least periodic sounding of one or more notes provides a harmonic base for the performance. This clarifies the scale structure and makes it possible to develop complex modes.

Components of the Drone

Indian drones may utilise anything from a single note to all of the notes of the scale. The complexity of the drone has an important bearing upon the feel of the performance.

The simplest drone consists of a single note repeated indefinitely. When only a single note is used, it must be the Sa (shadaj) of the piece. Single note drones may be found in folk music (e.g., ektars) but sometimes they may be found in classical music. A single note is all that is required to define the modality of the piece.

More complicated harmonic effects may be produced by having two notes in the drone. Both Hindustani sangeet as well as Carnatic sangeet tend to use the first and the fifth (e.g., Sa-Pa) as a drone. Folk music on the other hand, permits many other combinations. The dotar for example may be tuned to a variety of intervals.

Occasionally, drones are even more complex. For example, five, six, and even seven-string tanpuras are available that provide far more than a simple Sa-Pa drone. The surmandal contains all of the notes of the scale spread over several octaves. Although these lush drones are available, there is a tendency to use them judiciously; otherwise the performance may become muddy and the modes indistinct.

Psychoacoustics of the Drone

We mentioned that having one, two, or even more components of a drone has an impact on the overall character of the rag. This raises the obvious question as to what the psychoacoustic mechanisms behind this phenomenon may be.

The relationship between different musical tones is characterised by different levels of consonance and dissonance. As explained elsewhere in this site, consonance is a feeling of repose and peace that occurs when there is a simple mathematical relationship between the frequencies of the musical tone. Dissonance on the other hand, is a feeling of tension which comes when such frequencies have a complex mathematical relationships.

It must not be construed that consonance is good and that dissonance is bad. Music is produced by the interplay of these two aesthetics in the same way that contrasting pungent or sharp spices with sugar makes for a pleasant culinary experience. A similar aesthetic is found in literature and film where the presence of villain or some overwhelming physical or psychological danger is necessary to provide an impetus to move the narrative along.

Consonance/dissonance may express itself in melodic situations, but it is most prominent when tones are present simultaneously. Since Indian music is based upon monody, this aesthetic would be very weak without the drone.

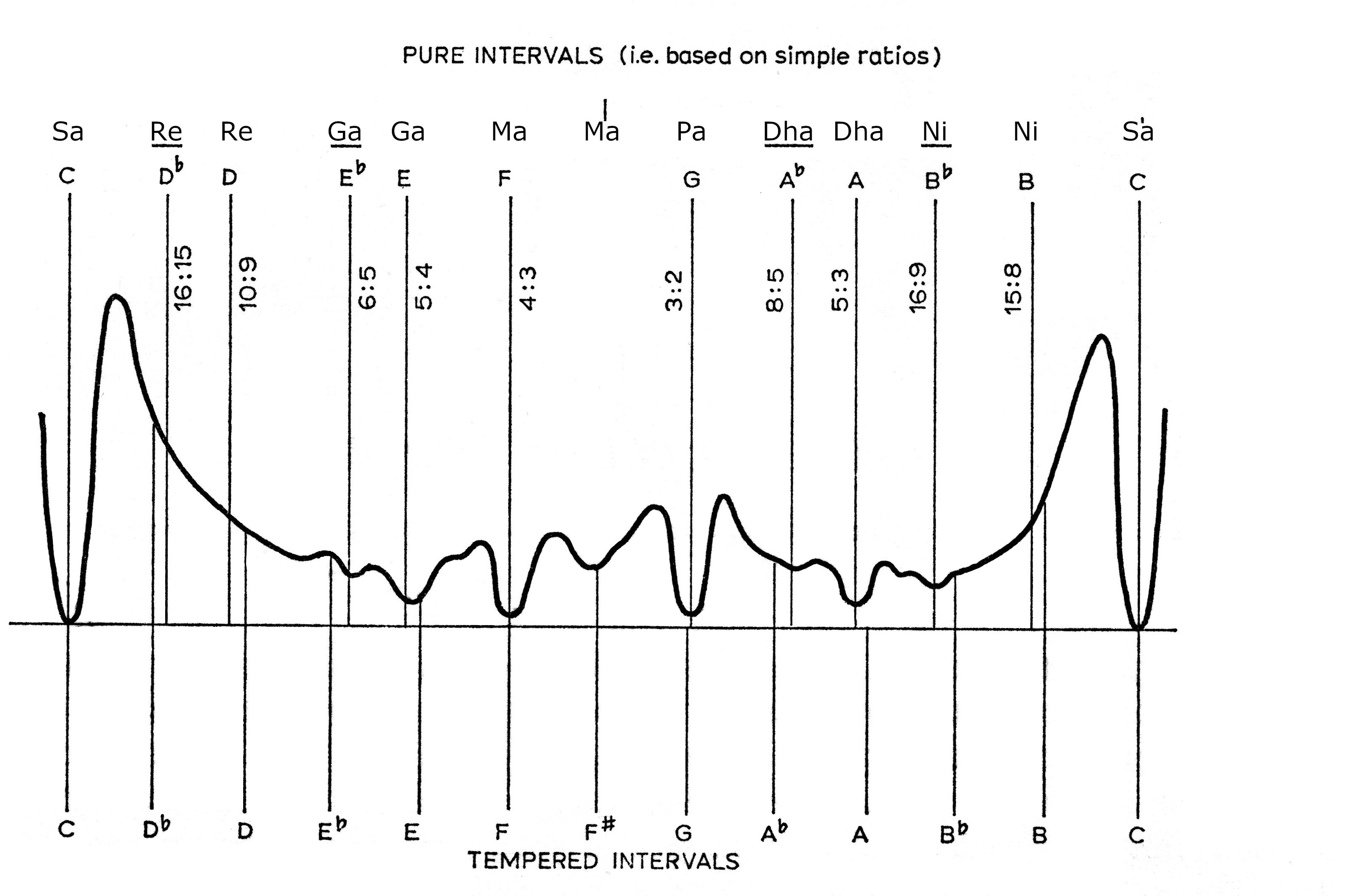

If a simple Sa drone is present, the level of consonance/dissonance may be expressed in Helmholtzian terms with the following chart:

The previous chart shows us several thing. Note that the higher values reflect higher levels of dissonance while the lower values reflect a greater level of consonance. (i.e., a lower value of dissonance.)

A single drone has a powerful effect on a monodic system such as Indian classical music; but India tends to use drones with multiple components.

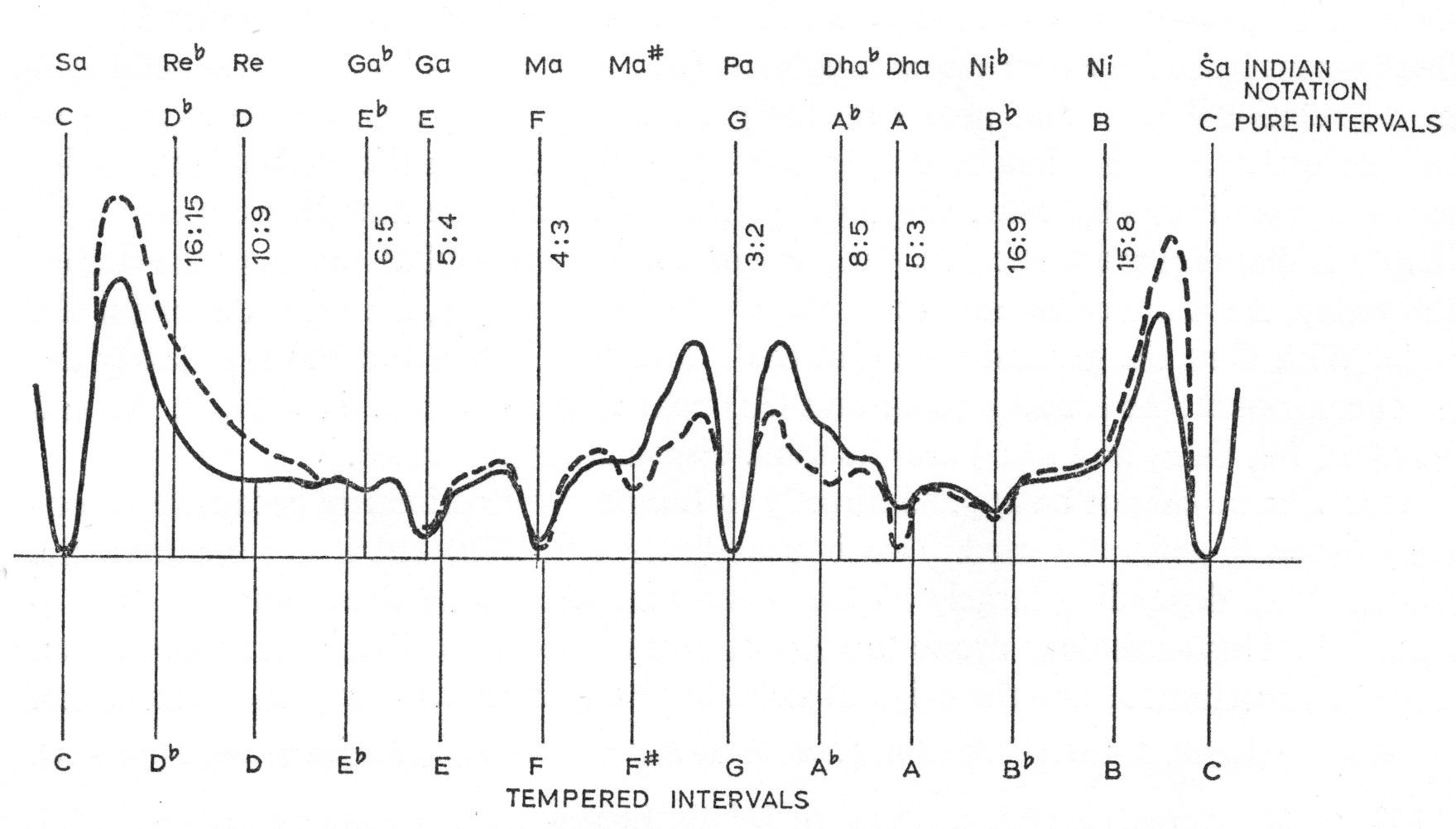

The addition of just a single additional component has a profound affect. N.A. Jairazbhoy, in the third quarter of the last century noted that the simple Helmholtzian relationship of the previous function could be altered by the addition of the Pa in the drone. This is derived from the simple and obvious fact that the secondary element in the drone brings with it its own function of consonance/dissonance.

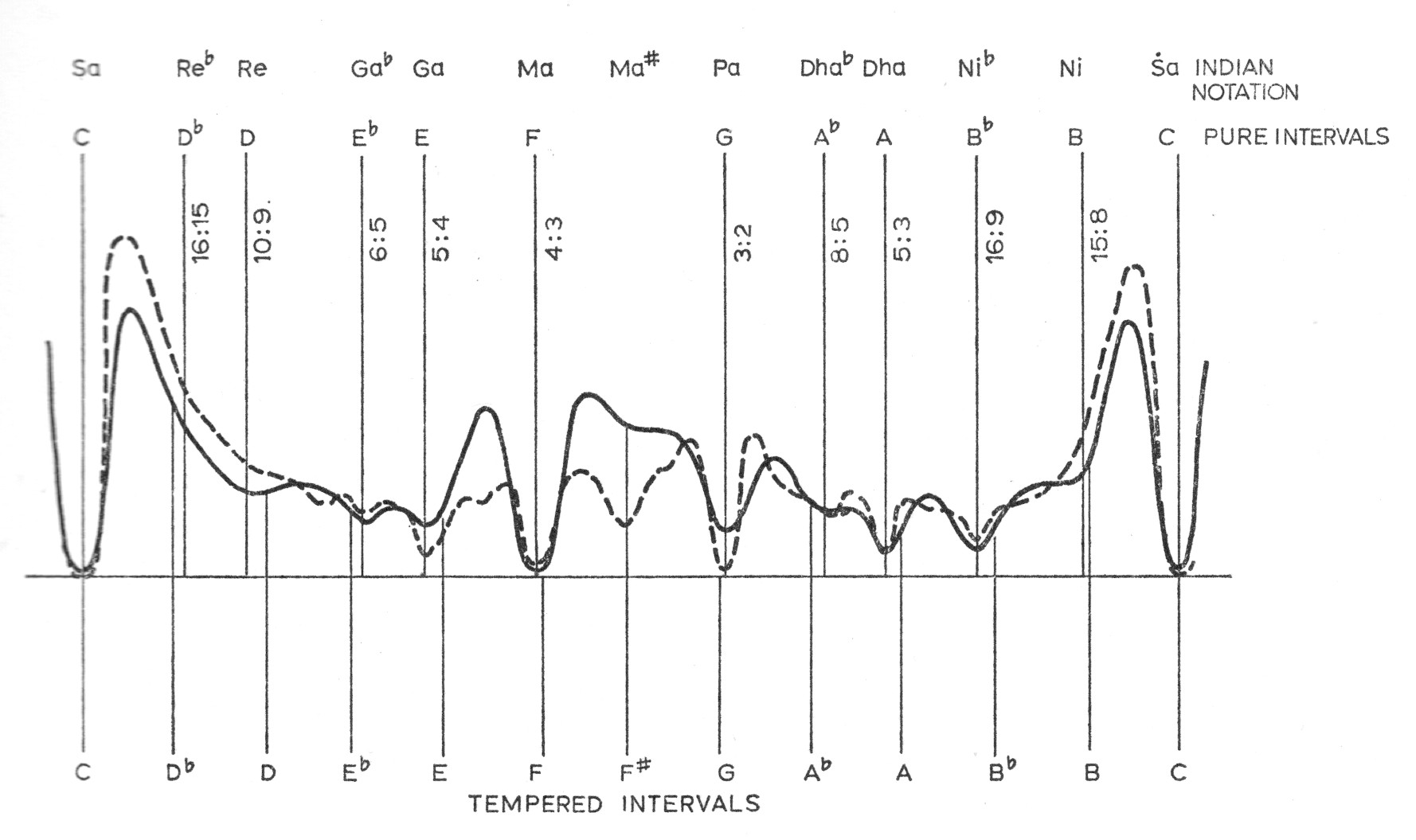

When Jairazbhoy applied the same process using Ma instead of Pa, he observed the following function:

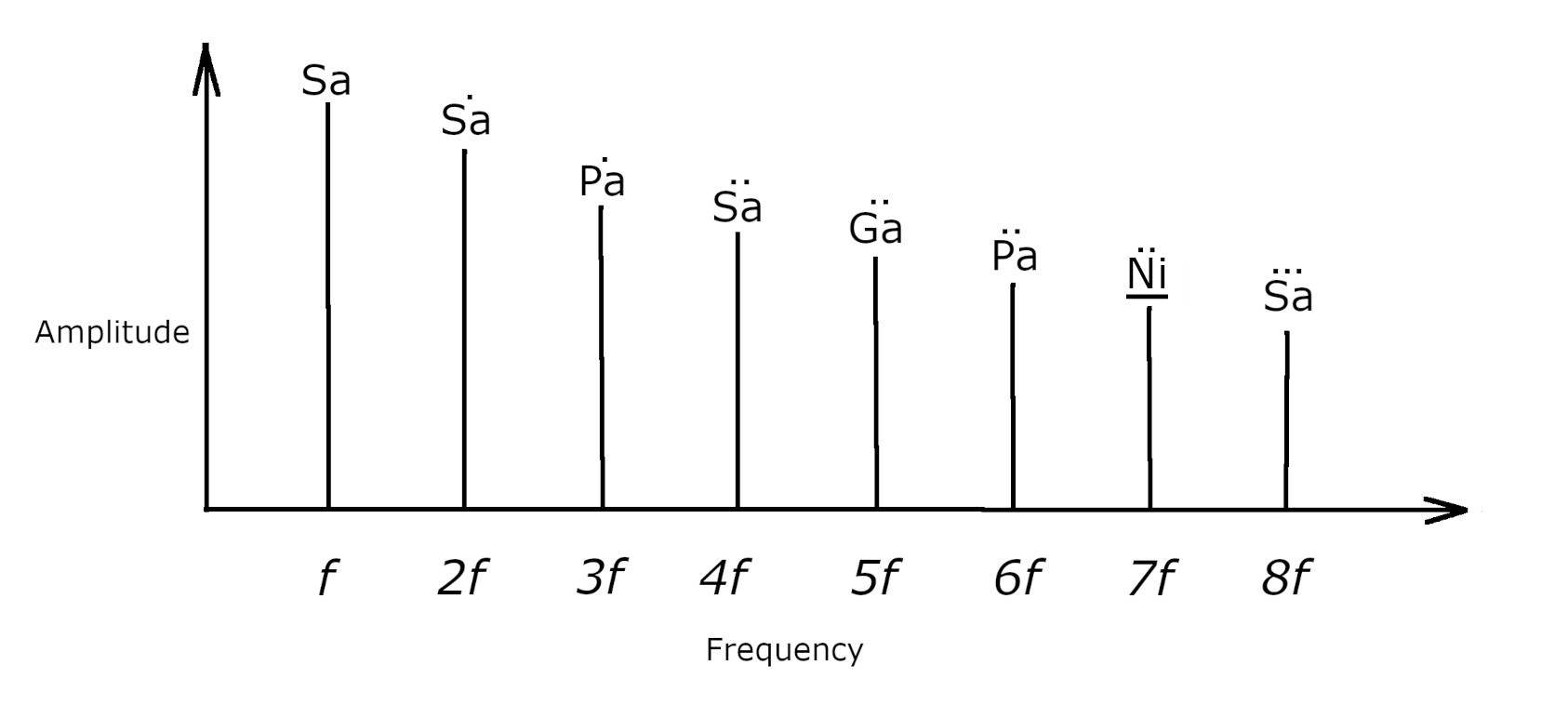

The work of Jairazbhoy is very interesting, but there is one thing that he did not adequately address. Helmholtz’s original work was done by comparing the sound of two violins. But it has been observed as far back as the work of C.V. Raman (Raman 1921) that Indian instruments such as the tanpura, have an extraordinarily rich overtone series. This is often due to specially designed bridges known as “jawari”.

Although the overtones in a harmonic spectrum seldom determine the pitch, they can greatly influence the sensation of consonance/dissonance. This phenomenon is strongly felt by piano tuners who rely on the slight inharmonic characteristics of the strings to “stretch” the octaves to a greater extent than would be expected from an ideal octave.

The musical significance of an ideal harmonic spectrum would be as follows:

The harmonic structure of our drone has a tremendous impact. Each spectral component (harmonic) carries its own pattern of consonance/dissonance.

It is clear that the physics and psychoacoustics behind the drone is very complicated. The subjective nature of the perception of sound poses obstacles to its study that those who merely wish to study the physics of sound do not have to deal with. Such studies push reductionism to its very limits.

Drones and Rhythm

Indian music displays a curious overlap between drone accompaniment and rhythmic accompaniment. It is normal for instruments, or parts of instruments, to be considered both a rhythmic support and a drone. Ektars and dotars are common examples in folk music. The same can be said for the chikari strings of the sitar or the thalam strings of the veena. Even the mridangam and the tabla, which are considered by many to be the ultimate rhythmic instruments, continuously drone the tonic. In contrast, instruments whose only function is to drone (e.g., tanpura, surpeti) are few.

The Drone and the Rag

It is appropriate for us to discuss to the use of drones with the various north Indian rags. Heretofore, we have discussed the drone in very broad terms, but it is now appropriate for us to narrow our focus.

In classical music, there is a tendency to think of the drone as a two-note musical device. As a practical matter, it is easy to think of this as being composed of a primary and a secondary drone. The primary drone will be Sa, and there will be one other note as the secondary drone.

It is obligatory that the primary drone be Sa; but one may find several different drones of Sa spread across several octaves. For instance, a stringed instrument such as the sitar, may have several strings set to Sa in different octaves, but at least one Sa must always be present. Just as Sa can never be omitted from any rag, in a similar manner, Sa should not be eliminated from the drone.

The secondary drone is up to the discretion of the artist. If this note is chosen unwisely, it can destroy the entire mood of a rag. Fortunately, an easy rule of thumb is to use the fifth (pancham). This works so often that one seldom has to give it a second thought. Unfortunately, there a few rags whose performance may be ruined by the presence of the 5th.

Here is an easy way to determine what the secondary drone should be.

- If Pa is present, one should give preference to it. This is the most common situation.

- If Pa is completely omitted and there is a shuddha Ma, then shuddha Ma is the preferred secondary drone. This situation is not that common, but it occurs often enough that the musician needs to be aware of it. Malkauns and Chandrakauns are two common examples.

- If Pa is totally absent and Ma is tivra, then one should tune the secondary drone to either Ga, Dha, or Ni. Dha is usually preferred. This situation is not very common, but it does show up in rags such as Marwa and Gujari Todi.

This last situation deserves some explanation. One should avoid use tivra Ma as a secondary drone; the reason for this is simple. Since the interval between Sa and tivra Ma is the same interval as tivra Ma to the higher Sa, it leaves the entire performance ungrounded. The listener tends to get confused as to which is the Sa and which is the tivra Ma. It therefore, leaves the modality of the entire piece in question. A good visual analogy of this situation is the classic “two face / vase illusion”; this is the picture where you can look at it one way and see a vase, or you can look at it another way and see the profile of two faces pointing at each other.

Although tivra Ma is not acceptable as a secondary drone, it is acceptable as a tertiary drone. For instance, if one were playing Marwa and there was already a drone of Sa, and Dha, then it would be quite acceptable to add a tivra Ma. The presence of the Dha against the Sa would keep the performance sufficiently grounded so that there would be no confusion from the addition of tivra Ma.

Drone Instruments

There are many Indian instruments whose only function is the drone. They are either incapable of playing a melody, or do so infrequently.

Tanpura – The tanpura is the most popular drone instrument in the classical tradition. It is a medium to large size lute. (more info.)

Surpeti – The surpeti is a box. It may be electronic or it may be a fixed reed instrument. (more info.)

Surmandal – The surmandal (a.k.a. swarmandal) is a small harp. It is a drone instrument which contains all of the notes of the rag. (more info.)

Ektar – This is a small one-stringed instrument found in folk music. (more info.)

Dotar – The dotar is similar to the ektar, but it has two stings. (more info.)

Drone Strings

It is very normal for Indian stringed instruments to have drone strings; this is part of a triad of functions which strings fulfil. The other components of this triad are playing strings and sympathetic strings. Of this triad, drone strings are commonly plucked or bowed, but not fretted or fingered. This is in contrast to the sympathetic strings which are not manipulated at all, but merely vibrate with sympathetic vibrations. Both of these functions are in contrast to the playing strings which are frequently fretted/fingered.

Ambiguity of Strings – The function of the various strings, may or may not be clear. In some cases the function of a particular string may be clear. For instance among the playing strings, there is usually one which is kept in such constant use that its function as a drone is precluded. In a similar way there are strings which may be plucked/bowed but are situated in such a way that fretting or fingering them is impossible. Such strings are purely drone strings.

But the distinction between these functions is not always clear. Sympathetic strings are largely inaccessible, but in spite of this, they may occasionally be strummed to act as a drone. Similarly, many of the playing strings are fretted/fingered so infrequently that for all practical purposes they exist merely as drone strings.

Key Changes – In spite of these ambiguities, we may be able to point out the drone strings of a musical instrument; but it isn’t always easy to say what they should be tuned to. We already discussed the merits of Sa, Sa/Pa, or Sa/Ma tunings. The previous discussions presumed that the factors of string material, string gauge, and more importantly – time, were under our control. But the logistics involved in using stringed instruments in any accompanying capacity, especially the accompaniment of the voice, often mean that we do not have much control.

Accompaniment poses great challenges due to key changes. Indian musical instruments are designed to play from a default key; but the realities of accompaniment force us to play from different keys. In an ideal world, one would have an instrument for every situation. In reality, one is doing very well if one can have two or three instruments of different keys.

One common way to change the key of our instrument is to have multiple baaj tars (playing strings). One may then switch them out according to the situation. When this approach is combined with a creative approach to tuning, one may do very well.

But replacing the main playing string and retuning an instrument takes time. There will be many situations where we will not have this time. In such cases one is forced to fall back upon creative tunings alone. When faced with this situation, the results may be passable, but suboptimal.

These realities will be reflected in our discussion of the drone strings. In the following discussion, we will talk of the drone strings and their tuning under ideal conditions. But these are general recommendations that are subject to change.

With these caveats in mind, we will undertake a brief description of the drone strings for common Indian instruments:

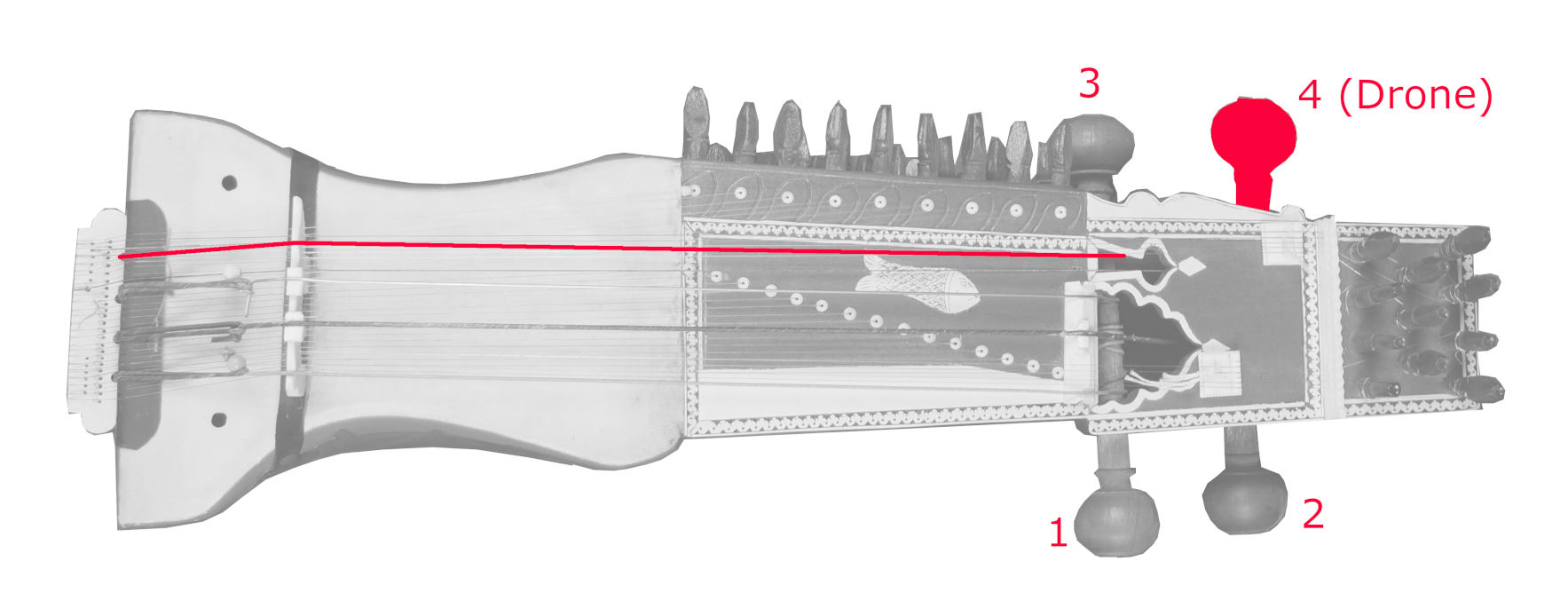

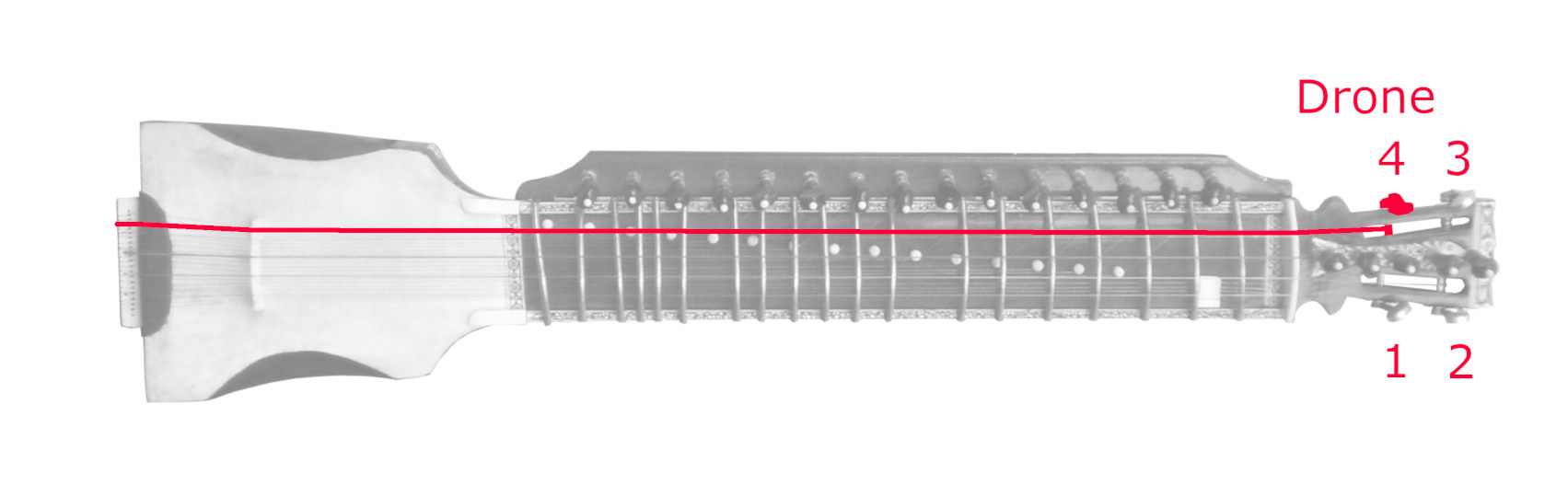

Sarangi – There are many types of sarangis, and several approaches to the drone. In the case of the classical sarangi, (illustrated below), the drone string is largely vestigial. Some players even remove it entirely; this is because strings 2, and 3 can also function as drone strings. There is a different approach for folk versions. Where the classical version has string 4 as the drone string, many folk versions have the drone on string 2. (Bor 1986)

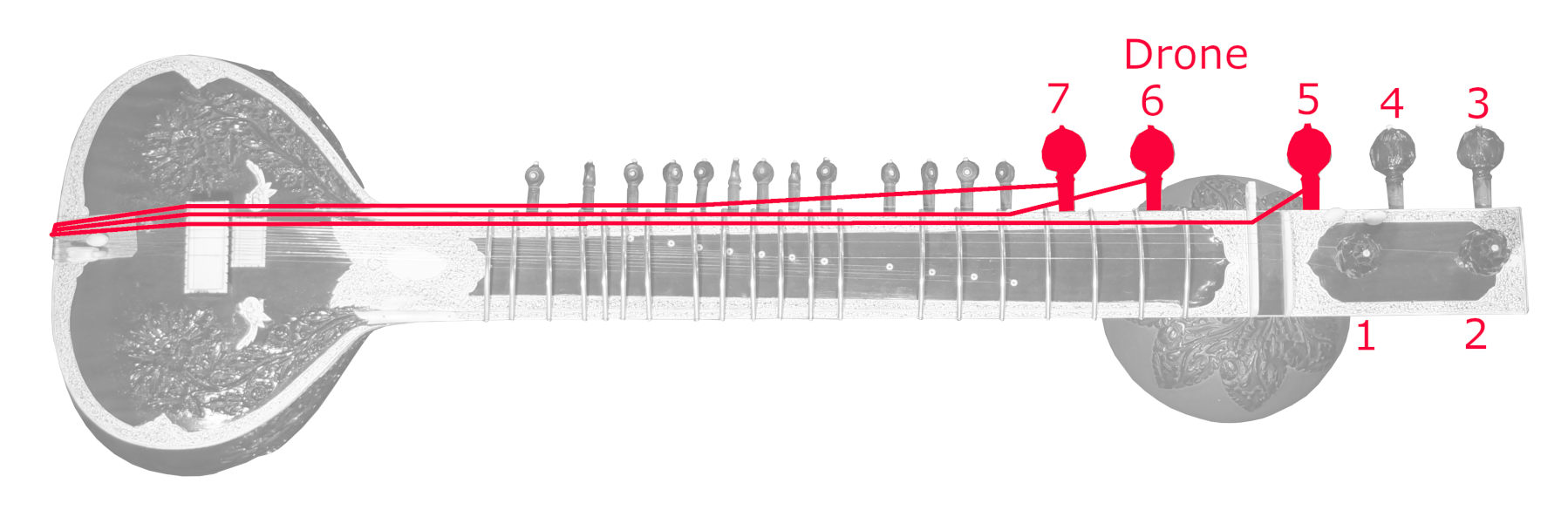

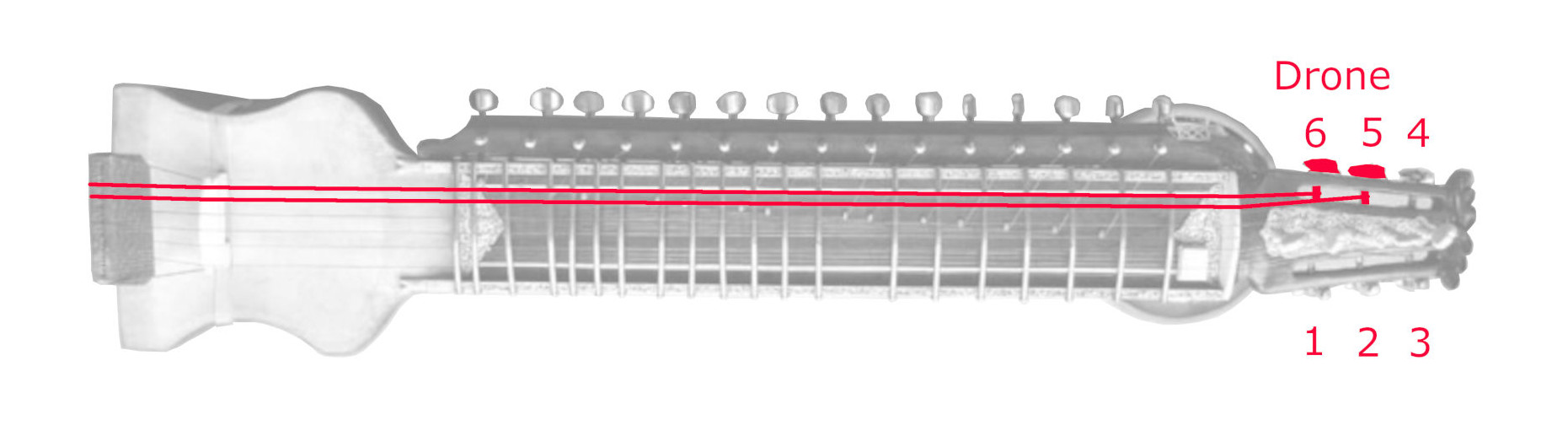

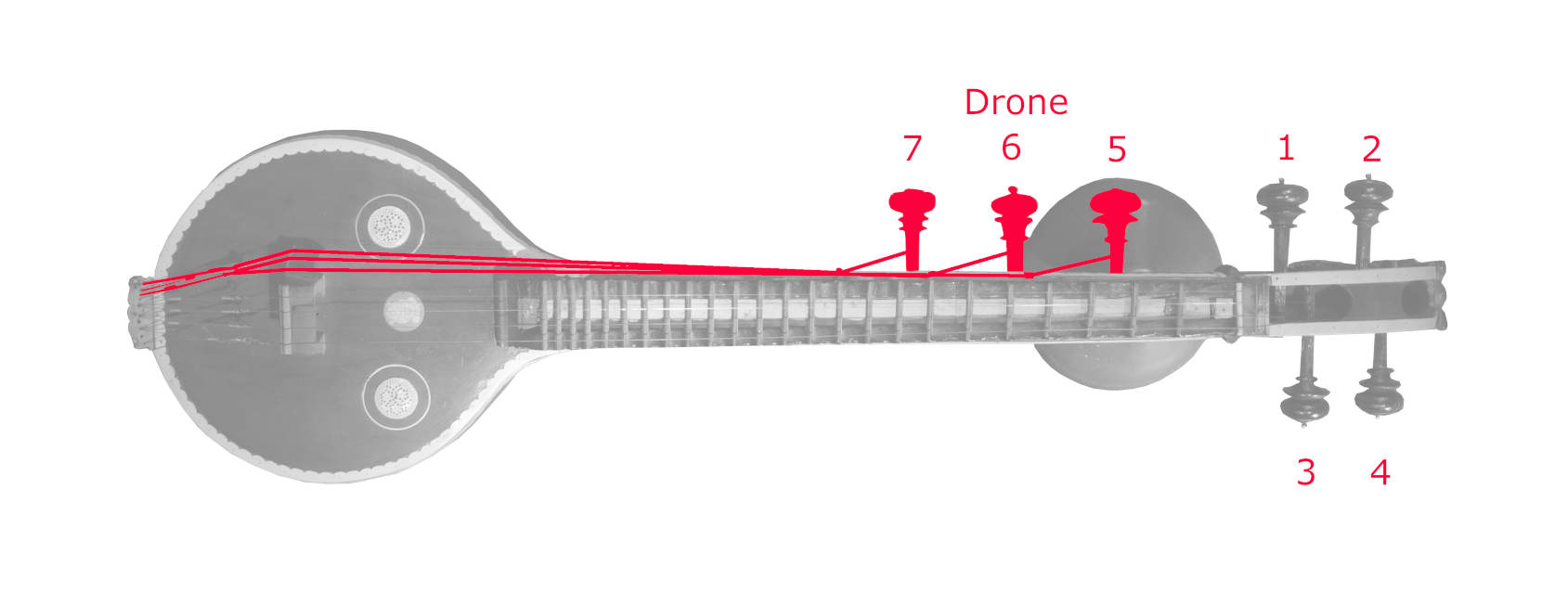

Sitar – There are numerous approaches to the stringing and tuning of the sitar. The mere effort of keeping track of them is a significant academic endeavour in its own right (Ghosh 1992). This makes it difficult to make definite statements as to number and tuning of the drone strings.

Some of the strings are unambiguously drone strings (Bhatnagar 1971). Strings 6 and 7 pass over small camel bone posts known as “chikari” (Junius 2001). These are located so far from the frets that any attempt to fret them cannot be considered. Strings 6 and 7 are tuned to Sa. String 5 passes over the frets but it cannot be fretted; this is usually set to Sa or Pa but may be tuned to anything which is musically appropriate.

However, making further statements as to the drone strings can be problematic. Much of the difficulty results from the ambiguity of the drone/playing strings; this was alluded to earlier. The playing strings, with the exception of the main playing string, definitely act as a drone. This action can be so extreme that many sitarists employ a small hook to lock strings 2 and 3 away, to keep them from droning (Chaudhury 1990).

String number 4 may or may not be a dedicated drone string. It passes over the frets; therefore one’s first impression would be that it is a playable string. However in many cases, an attempt to play this string shows that the geometry of the fret and upper bridge is such that one will never get useful results. In such cases, string number 4 can only function as a drone string. As such it may be set to any pitch which is musically appropriate. But there is a style of sitar which was popularised Ravi Shankar that is designed and built in such a way that string number 4 is playable. It uses a very heavy string that extends the playing range into Sa of the lowest octave (Shankar 1968).

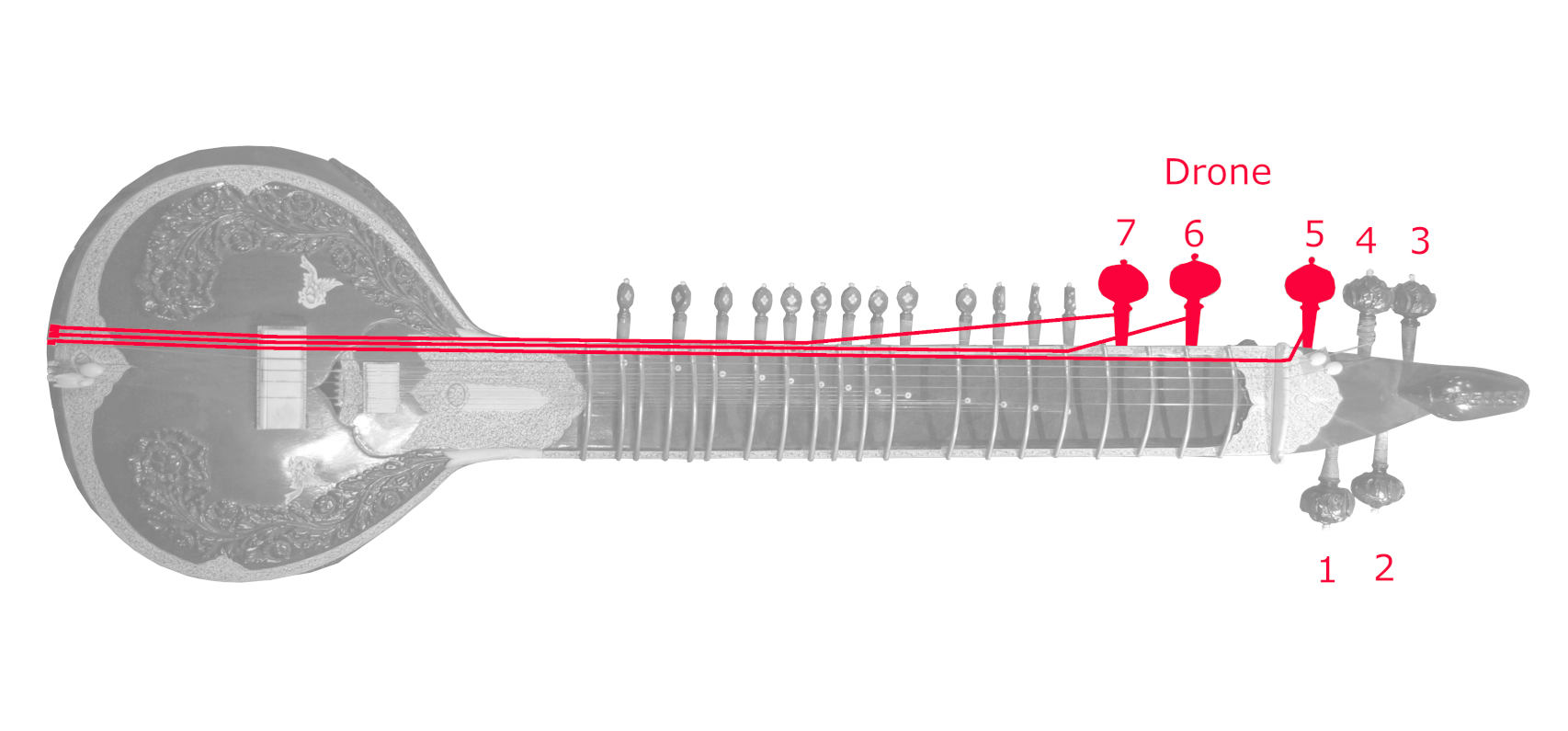

Surbahar – The surbahar is basically a bass sitar. As such most of the comments that we made for the sitar also hold true for the surbahar.

Esraj – The drone string on esraj is typically string number 4. It has a position and gauge such that it serves no other function. Ideally this string should be tuned to Sa or Pa. However strings 2 and 3 may serve dual functions as being playing strings or drone strings. String number 1 is the playing string.

An alternative stringing/tuning system has been put forth by M. Wheeler in his “A Practical Method for Taus, Dilruba, and Esraj” (Wheeler 2012). In this work, he proposes a tuning of mandra Ma, mandra Sa, mandra Sa and ati mandra Pa, for strings 1, 2, 3, and 4 respectively. This has strings 2 and 3 both set to the same note. Although it is a very unusual tuning, it does have the advantage that a drone string is accessible from any playing string, thus giving it the greatest flexibility in terms of drone.

Dilruba – The dilruba is merely a regional variation upon the esraj. The same comments apply.

The six string dilruba, or esraj has the same philosophy as the more common four string versions. The only difference is that is that the playing range is extended downward half an octave via string 4, and there are two drone strings (5 and 6). This additional drone string allows for a Sa-Pa tuning.

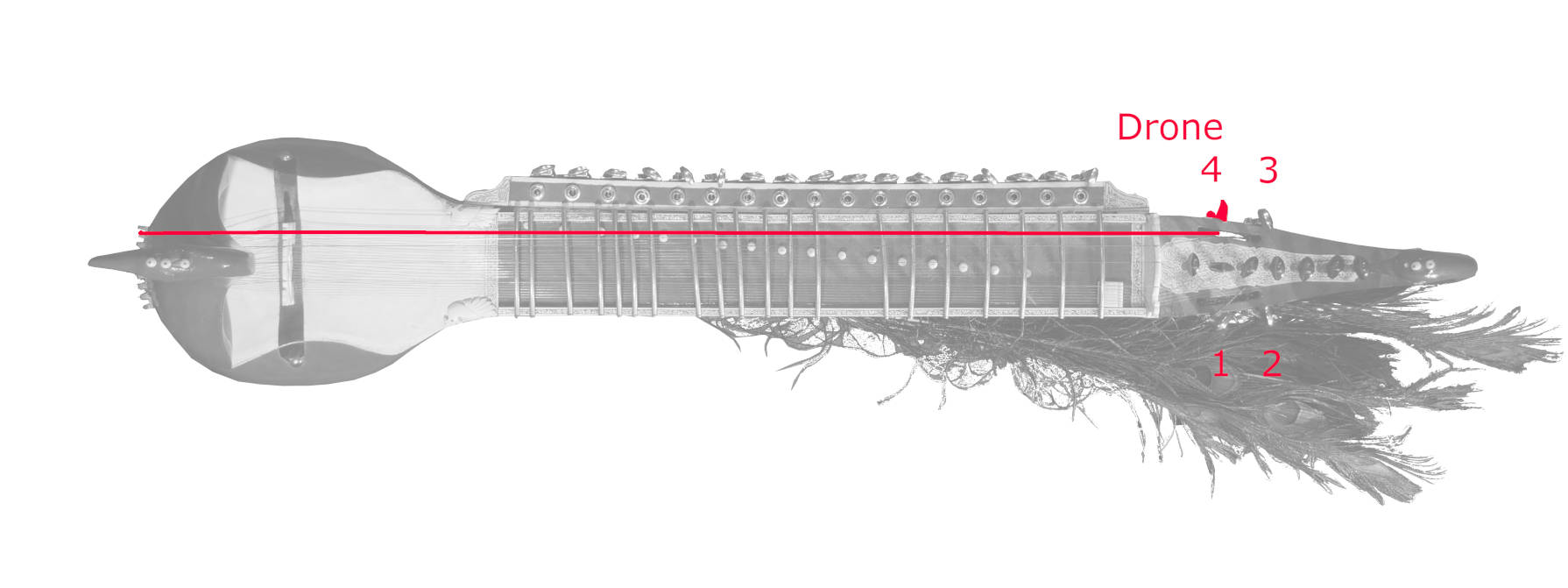

Taus – The taus is in the same family as the dilruba and esraj. The word “taus” means “peacock” (McGregor 1993). It has the same arrangement of drone strings and playing strings as the dilruba or esraj.

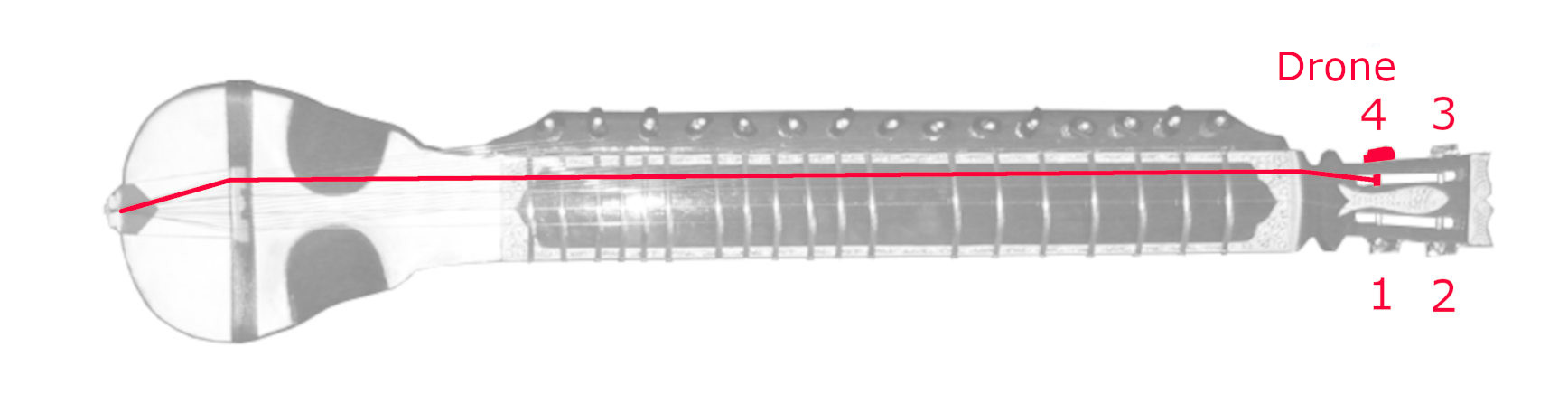

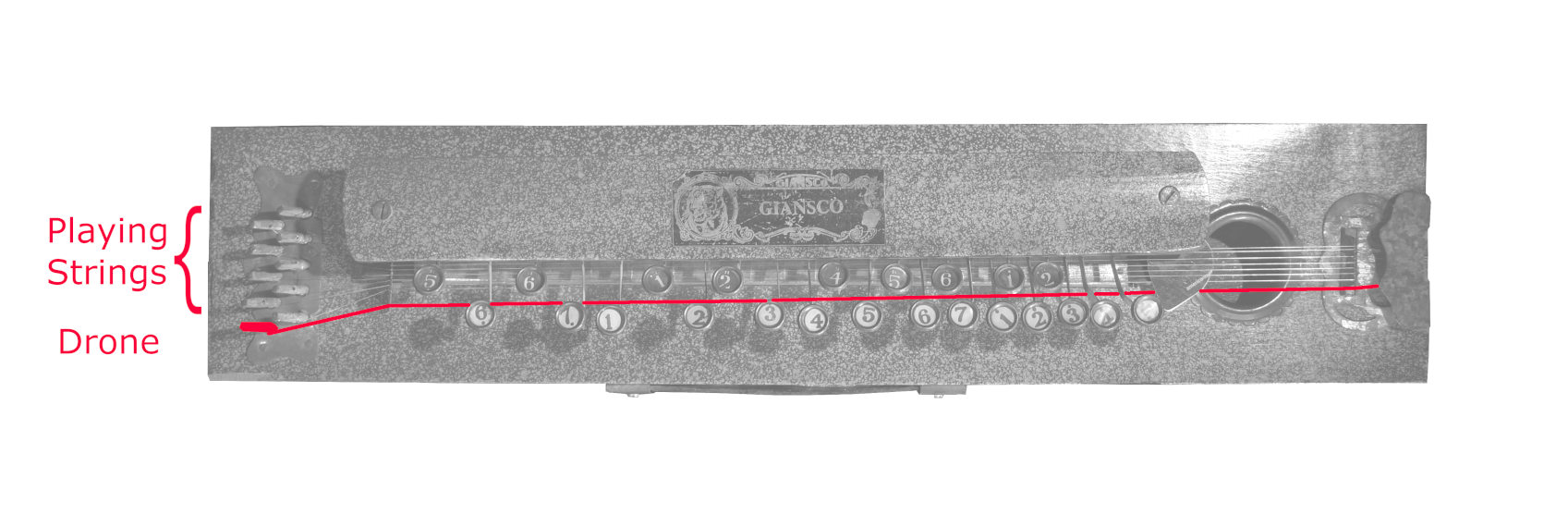

Bulbul Tarang – The bulbul tarang (a.k.a. banjo), is one of the few stringed instruments in India where there is no ambiguity between a playing string and a drone string. Its construction is such that strings must either bypass or pass under the keyboard; there is no in between.

Never-the-less, it is hard to make generalisations about the bulbul tarang. There is an extreme variety of of sizes and numbers of strings. Furthermore among the Indian versions, the uppermost and lowermost strings are generally user configurable to be either playing strings or drone strings. The example shown above has a single drone string located in the lower section of the instrument.

Saraswathi Veena – This is the typical south Indian veena. It has three dedicated drone strings which pass over three protuberances (moggu) on the middle portion of the neck. (Balagopal 1982). They then pass over a curved brass bridge which is adjacent to the main bridge (Krishnaswami 1965).

The tuning and stringing of the veena is different from north Indian instruments, so some discussion is in order.

Most north Indian stringed instruments follow a common pattern. The uppermost strings are dedicated drone strings. The next group of strings are the dual purpose, drone/ lower octave playing strings, while the main playing string (baaj taar) is located at the bottom.

However the veena is put together differently. It has the uppermost strings as the dedicated drone strings (i.e., the thalam at 5, 6,and 7), then it has the main playing string (the sarani) at string 1. The lower octave playing-cum drone strings are located at the bottom (strings 2, 3, and 4. This has profound implications, because this forces the thalam (drone) and lower octave strings to have different techniques when used as drones.

Sarod – The sarod is known for its rich sound. One of the reasons for this richness is the particular importance given to the drone strings.

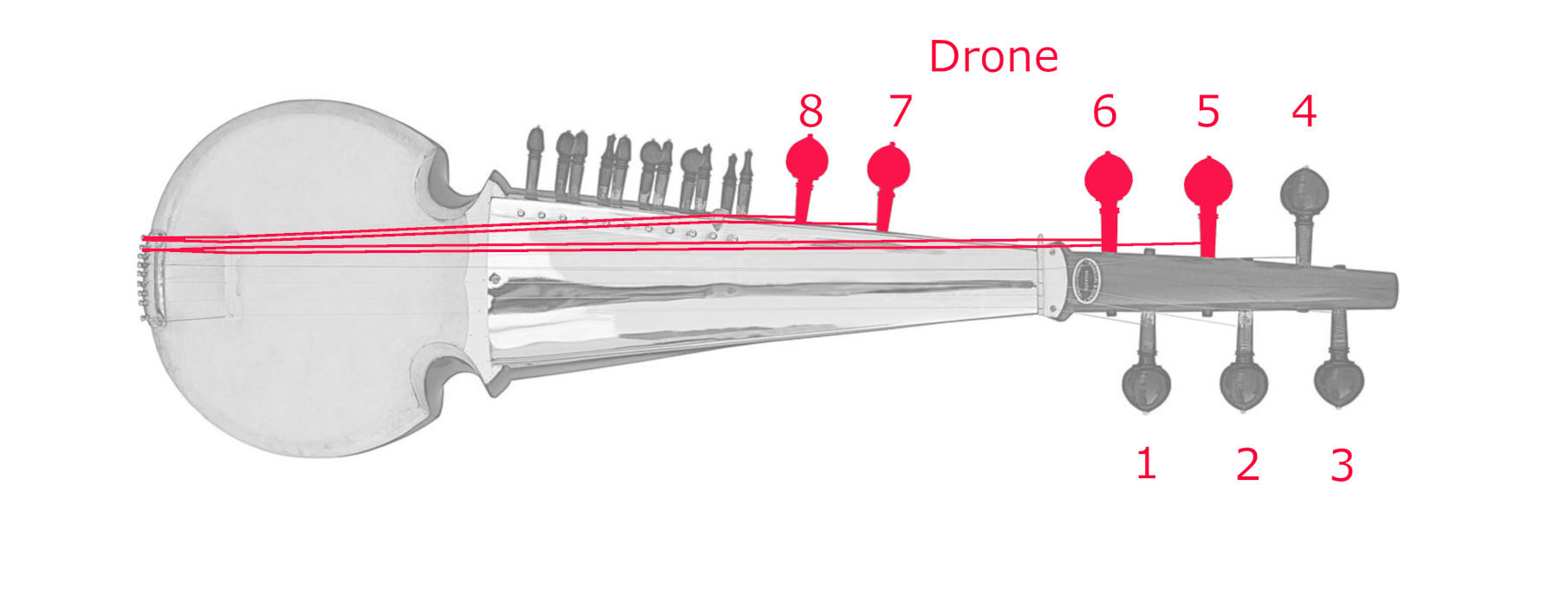

There are two basic styles of sarod. There is the Delhi style and the Calcutta style (a.k.a Maihar style).

The Delhi style (shown below) is much closer to the original rabab in construction. As with other North Indian stringed instruments, the lower octave playing strings (i.e., 2, 3, and 4) can function as a drone. But in addition to these, there are four dedicated drone strings. Of these string 5 may be tuned to either Pa, Ni, or Sa; while strings 6, 7, and 8 are tuned to Sa (I. Khan 1999). Strings 7 and 8 are notable in that they pass over a chikari located midway down the neck.

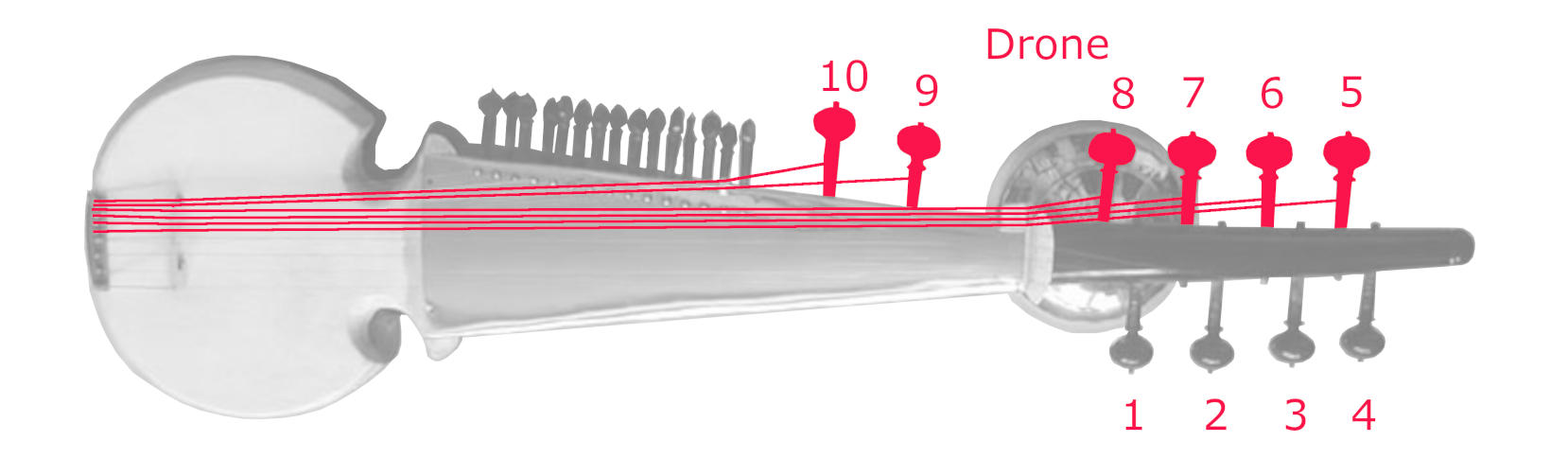

This would be an impressive number of drone strings in its own right, but it pales in comparison to the Calcutta style sarod.

A notable characteristic of the Maihar style sarod is the addition of jawari drone strings. These are noted as strings 5, 6, 7, and 8. The jawari is characterised by a broad flat bridge, in this case located at the upper bridge on the neck. This is a relatively recent addition which is attributed to Baba Allaudin Khan (1862-1972) and his brother (A. Khan 1991). The tuning of these four jawari strings may vary, but one common tuning is Ni, Re, Ga, Sa for strings 5,6,7, and 8 respectively (I. Khan 1999). Strings 9 and 10 will of course be tuned to Sa.

The Harmonium and Other Instruments

Stringed instrument are not the only ones which may also contain a drone. Drones may be associated with other instruments. Most of these are folk instruments. The snake charmers’ instrument known as “pungi” or “bin” is a common example.

The harmonium is the most common classical instrument that falls into this category. Most Indian harmoniums have five stops for drones. These are usually tuned to C#, D#, F#, G#, and A#.

Drone Apps and Software

Today there is a plethora of apps that provide a drone. Sometimes it is a simple sine wave tone that is part of many electronic tuner apps. Sometimes it is a dedicated app, sometimes it is a small part of a package whose main focus is something larger (e.g., lahara). These are so ubiquitous and humble, that they really do not warrant much discussion.

Conclusion

This page has gone over the drones of Indian music in some detail. At first, the drone may appear to be trivial, but it is not. The drone is necessary to define the modality of the piece. Sometimes this is very simple. Other times, it requires a sophisticated understanding of the structure of the rag.

Selected Video

Works Cited

Apte, Vaman Shivram

1995 The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

Balagopal, Tara

1982 Learn to Play on Veena. New Delhi: Pankaj Publications.

Bhatnagar, Jyotiswarup

1971 Sitar Shikshak (Vol 2). Lucknow, Jyotiswarup Bhatnagar.

Bor, Joep

1986-87 The Voice of Sarangi; An IIlustrated History of Bowing in India. Bombay: National Centre for the Performing Arts.

Chaudhury, Deepak

1990 “Maihar Gharana”, Seminar on Sitar. Bombay: ITC-SRA (Western Region).

Ghosh, Sharmistha Sen

1992 String Instruments of North India (Vol. 2). Delhi: Eastern Book Linkers.

Jairazbhoy, N.A.

1971 The Rags of North Indian Music: Their Structure and Evolution. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Junius, Manfred M.

2001 The Sitar: The Instrument and its Technique. Varanasi: Indica Books.

Khan, Ashish

1991 “The Contribution of Maihar Gharana to th Evolution and Technique of Sarod”, Seminar on Sarod. Bombay: ITC-SRA (Western Region).

Khan, Irfan Md.

1991 “Paper Presented by Irfan Md. Khan”, Seminar on Sarod. Bombay: ITC-SRA (Western Region).

Krishnaswamy, S.

1965 Musical Instruments of India. Delhi: Publications Division, Govt. of India.

Little, William, et al.

1937 Oxford Universal English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc.

McGregor, R.S.

1993 The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Raman, C.V.

1921 “On Some Indian Stringed Instruments”, Proc. Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science 7 29-33, IACS (1921).

Randel, Don Michael

1978 Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music. Cambridge: Belknap Press (Harvard University Press).

Rosenthal, Ethel

1928 Story of Indian Music and its Instruments. London: William Reeves Bookseller Ltd.

Shankar, Ravi

1968 Ravi Shankar: My Music, My Life. New Delhi, India: Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd.

Wheeler, Michael C.

2012 A Practical Method for Taus, Dilruba, and Esraj. Wheeler Studios.