The seni rabab is an instrument that was very popular during the Moghal period. The seni rabab came close to extinction, but in recent years has started to make a comeback.

This instrument comes in several forms. As one moves around in time and geography one finds tremendous variation. It becomes almost impossible to tell where the seni rabab, ends and other rababs begin. Some of the other instruments in the rabab family include the kabuli rabab, the swarabat of south India, and the dotora of Bengal. Even the kamancha of Rajasthan appears to be nothing more than a bowed version of the seni rabab.

The name “seni rabab” is interesting. It is an Indian corruption of the Persian “Sen-e-Rabab” which means “the rabab of Tansen”. Tansen was a great musician in the court of Akbar who is credited with the popularisation of this instrument. There are many who (incorrectly) attribute the invention of the seni rabab to Tansen. The seni rabab is also referred to as the “Indian rabab”, to distinguish it from the kabuli rabab. The kabuli rabab is originally from Afghanistan, but today commonly found in Pakistan and Kashmir.

This instrument was held in great esteem in the past. The first Guru of the Sikhs, Guru Nanak is said to have had tremendous love for the instrument. It is said that he was accompanied by has friend and musical accompanist Mirdana while he sang the Gurbani. It is the rising interest in gurmat sangeet (Sikh religious music) which is primarily responsible for the reawakening in interest in this instrument.

| Are you interested in a secular approach to teaching Indian music. |

|---|

Indian music is traditional taught in a fashion that is linked to Hindu world views. But there are situations, often in schools, where this approach may not be the best. In such situations The Music of South Asia may be the best resource for you. |

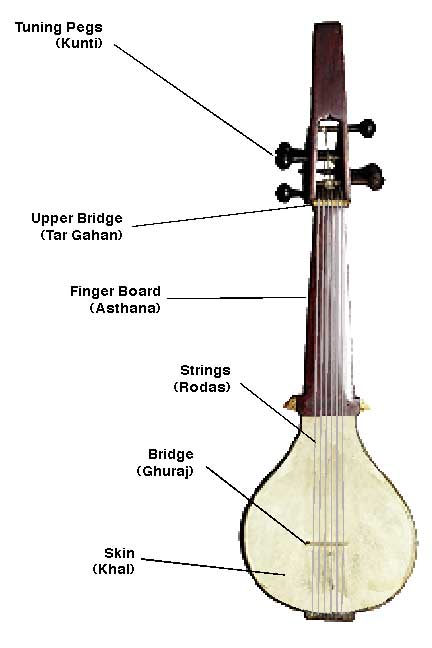

Parts of the Seni Rabab

There are a number of parts of the seni rabab. These are shown in the illustration below:

Parts of the Seni Rabab

The seni rabab consists of a body which is hollowed out of wood. There is a large hollowed out bowl which is covered with thin goat skin (khal); this forms the resonator. There are two bridges on the instrument; the one on the skin is known as the guraj while the upper one on the neck is known as the tar gahan. There are six strings known as rodas. They are affixed to six wooden tuning pegs (kunti) at the upper end. They are also affixed at the lower end. There are no frets to the seni rabab, only a wooden finger board. The fact that this finger board is made of wood, and not covered with a metal plate, means that only soft strings can be used. These are usually of gut; however on modern instruments, one often finds that nylon is used.

The construction of the seni rabab is interesting, not just for what is found, but probably more for what is not found. Traditionally, the seni rabab did not have sympathetic strings (tarafdar); however, some modern instruments include them. Furthermore, they did not have chikari strings as we have come to expect on modern instruments. Still, the lower strings of this instrument do function as drone strings in much the same way as the lower strings of a sitar, esraj, or dilruba, may function as drone.

Tuning the Seni Rabab

Anyone with any experience with Indian musical instruments should not be surprised to find that there are several tunings for the seni rabab.

It must always be remembered that the tuning of Indian stringed instruments is a reflection of how a particular artist feels about their music. Stringed instruments are typically tuned differently for different rags and different styles. Many times an artist will use a different tuning for each piece. One should keep this in mind as we go over several tunings here. For these, kindly refer to the illustration below:

Seni Rabab Strings

Tuning #1 – The table below is a very traditional tuning for the rabab:

| String | Pitch | Name of String |

| 1 | Pa in Madhya Saptak | Zeer |

| 2 | Re in Madhya Saptak | Mian |

| 3 | Sa in Madhya Saptak | Sur |

| 4 | Pa in Mandra Saptak | Mandra |

| 5 | Ga or Ma in Mandra Saptak | Ghor |

| 6 | Sa in Mandra Saptak | Karaj |

Tuning #2 – Here is another tuning for the seni rabab. The last tuning may be traditional, but many people may be uncomfortable with the constant sounding of the Re. Therefore, in an effort to aid the revival of the rabab, many artists adopt a more contemporary approach to tuning. One example is shown in the table below:

| String | Pitch | Comments |

| 1 | Ma in Madhya Saptak | |

| 2 | Sa in Madhya Saptak | |

| 3 | Pa in Mandra Saptak | |

| 4 | Sa in Mandra Saptak | |

| 5 | variable according to the rag | |

| 6 | variable according to the rag | Many of the modern seni Rababs do not havea 6th string |

Tuning #3 – There is another variation upon this tuning which is sometimes employed.

| String | Pitch | Comments |

| 1 | Sa in Madhya Saptak | |

| 2 | Pa in Mandra Saptak | |

| 3 | Sa in Mandra Saptak | |

| 4 | variable according to the rag | |

| 5 | variable according to the rag | |

| 6 | variable according to the rag | Many of the modern seni Rababs do not have a 6th string |

Tuning Taraf Strings – It appears that taraf strings (i.e., sympathetic strings) on the rabab are a “recent” innovation. (The word “recent” might be several centuries, so you can interpret this word any way you wish.) If your rabab does have taraf strings, the question naturally arises as to how they are tuned. For this, one follows the same principles used in the tuning of the taraf strings on the sitar, sarod or any other north Indian instrument. That is to say that they may be tuned chromatically, or according to the rag, or some variation between these two approaches.

Playing the Rabab

Let us discuss some of the basic points that are important to playing the seni rabab.

Sitting Position – It is obvious that the sitting position is one of the most fundamental points to playing the seni rabab. However there is not just one way, we can describe at least four ways. These will be described below:

The illustration below shows a person standing while the rabab is suspended around his neck. Since the seni rabab was known to be a rather loud instrument, it was suited for outdoors processions. In such situations, this was a very workable arrangement.

The illustration below shows a way that appears to have been very common. In this position, one sits on ones knees such that the feet a facing the rear. The rabab is placed at a very steep angle over the left shoulder.

Neither comfort nor good control of the instrument are advantages of this approach. The main function is to avoid the misdemeanour of inadvertently showing the soles of your feet to the king, or honoured guests of the performance.

The illustration below shows a musician seated in a cross legged position with the instrument in his lap.

Below we see the rabab placed against the heel of the left foot in a position very much like that used for the sitar.

In this section, we presented four ways to hold the rabab. Do not think that these are the only ways to do it. I am sure that there are other positions; however, this sampling should at least give you an idea of the possibilities.

Plucking and fingering

Plucking is done with a triangular wooden plectrum, known as a java. This may be made of a variety of materials including, sandalwood, coconut shell, or bamboo.

Fingering is done with the left hand. usually the nails are employed. In this capacity it was common for musicians to grow their fingernails long. In other instances the scales of fish were glued on.