Introduction

Sitar is perhaps the most well known of the Indian instruments. Artists such as Ravi Shankar have popularised this instrument around the world.

Sitar is used in a variety of genre. It is played in north Indian classical music (Hindustani Sangeet), film music, and western fusion music. It is not commonly found in south Indian classical performances or folk music.

Sitar is a long necked instrument with an interesting construction. It has a varying number of strings but 17 is usual. It has three to four playing strings and three to four drone strings. The approach to tuning is somewhat similar to other Indian stringed instruments. These strings are plucked with a wire finger plectrum called mizrab. There are also a series of sympathetic strings lying under the frets. These strings are almost never played but they vibrate whenever the corresponding note is sounded. The frets are metal rods which have been bent into crescents. The main resonator is usually made of a gourd and there is sometimes an additional resonator attached to the neck.

| This book is available around the world |

|---|

Check your local Amazon. More Info.

|

Origin of Sitar

The development of the sitar, in general terms, is really no mystery. However, It is surprising that there have arisen theories and stories that show a total disregard for historical accuracy.

The most common story attributes the invention of the sitar to Amir Khusru. Amir Khusru was a great personality, and is an icon for the early development of Hindustani Sangeet. He lived during the reign of Allaudin Khilji around 1300 AD. As common as this story is, it has no basis in historical fact. The sitar was clearly nonexistent until the time of the collapse of the Mogul empire. Therefore, the theory that Amir Khusru invented the sitar may be discounted.

Another theory has the sitar evolving from the ancient veenas such as the rudra vina. However, the rudra vina is a stick zither while the sitar is a lute. There are also differences in materials used. It is not very likely that the sitar owes its origins to this instrument.

Some suggest that the sitar is derived from the Saraswati vina. This is at least a possibility. Still there are uncomfortable questions raised. Where did the Saraswati vina come from? Why does this class only begin to show up in India about 800 years ago? We must be open to the distinct possibility that the lute class of chordophones is not indigenous to India but imported from outside.

Ultimately the earliest origins of these instruments are irrelevant. It is clear that the sitar as we think of it today developed in the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent at the end of the Mogul era. It is also clear that it evolved from the Persian lutes that had been played in the Mogul courts for hundreds of years. Since this part is very clear, let us turn to other documents to clarify the picture.

The “Sangeet Sudarshana” states that the sitar was invented in the 18th century by a fakir named Amir Khusru. This of course was a different Amir Khusru from the one who lived in 1300. This latter Amir Khusru was the 15th descendent of Naubat Khan, the son-in-law of Tansen. It is said that he developed this instrument from the Persian sehtar.

The job of continuing the sitar tradition fell to Amir Khusru’s grandson, Masit Khan. He was one of the most influential musicians in the development of this instrument. He composed numerous slow gats in the dhrupad style of the day. This style, even today, is referred to as Masitkhani Gat. The Masitkhani gats were further popularised by his son, Bahadur Khan. Masit Khan was a resident of Delhi, therefore masitkhani Gats are sometimes referred to as Dilli Ka Baaj.

Another important person in the development of sitar music was Raza Khan. Raza Khan was also a descendent of Tansen and lived in Lucknow around 1800-1850. Raza Khan was also known as Ghulam Raza. He developed the fast gat known as Razakani gat.

Amrit Sen and Rahim Sen were two very important personalities. They modified the tuning and stringing of the instrument and introduced numerous new techniques to the instrument.

Parts of the Sitar

It is always problematic to discuss the names of the parts of the instruments. India is a land with many different dialects and languages. It is the norm for the parts of sitar to be called very different things in different places. Remember, the terms that we use here are fairly representative, but by all means not the only ones to be found.

Kunti – The kuntis are the tuning pegs. These are simple friction pegs. The sitar has two types: there are the larger kuntis that are for the main strings. There are also the smaller kuntis which are used for the sympathetic strings. The larger kuntis come in three styles: simple, fluted, and lotus. A quick look at the kuntis is usually an indication of the care that went into the instrument.

Baj Tar Ki Kunti – One of the most important kunti is the baj tar ki kunti. This is the one used for the main playing string. This one will be used more than any other.

Drone Strings – There are a number of strings on the sitar which are strummed but not fretted, these are referred to as drone strings. Two of the kuntis (pegs) control special drone strings; these are referred to as the chikaris. These two strings are raised above the neck on two camel bone pegs; these pegs are known as mogara. There are other drone strings which continue all the way down the neck.

These drone strings are important to the musical performance. During a normal performance, these strings will periodically be struck to provide a tonic base for the piece. The chikari are especially important in a style of playing known as jhala.

Tumba – Many sitars have a gourd which is attached to the neck. This is known as tumba. Not all sitars have a tumba.

Tar – A tar is a string. There a number of strings on the sitar. Numbers may vary, but 18 is a common number. These strings fall into one of three classes; there are the drone strings (previously described), the sympathetic strings, and the playing stings. The playing strings are the strings which are actually fretted to produce melodies. It comes as a surprise to many newcomers to Indian music that only one to four strings are actually played to produce a melody. In most cases there are really only two playing strings. These are the two strings located furthest from the sympathetic strings.

Baj Tar – The absolute furthest string is referred to as the baj tar which literally means “the playing string”. Virtually all of the playing is done on this one string.

Tarafdar – The tarafdar are the sympathetic strings. They are almost never strummed, yet they vibrate whenever the corresponding note is played on the playing string. They are located underneath the frets, so fretting them to produce a melody is impossible.

Dandi – This is the neck of the sitar.

Parda – These are the frets. These are metal rods which are bent and tied to the neck with fishing line. Although they are held firmly in place, they may be adjusted to correct the pitch. There are two pardas, the Re and the Dha, which require constant adjustment as one moves from rag to rag (see scale structure, that, and rag for more information).

Gulu – The gulu is a wooden cowl that connects the neck to the resonator. Although it does not command much attention for the casual observer, it is actually one of the most important parts of the instrument. It is a common problem on sitars for this part to be weak, especially where it meets the neck. If this is too weak then the whole instrument goes out of pitch anytime one meends (bend the note by pulling the string laterally across the fret). This is very annoying and is definitely a mark of inferior workmanship.

Chota Ghoraj – The chota ghoraj, also known as the taraf ka ghoraj orjawari, is a small flat bridge for the sympathetic strings. The highest quality ones are made of antelope horn. However, the high cost of this material makes them very rare. The most common material for fabricating them is camel bone. Camel bone is a very usual material that is used as a common substitute for ivory.

Bada Ghoraj (Main Bridge) – The bada ghoraj also known as jawara, or jawari, is similar in construction to the chota ghoraj. This is used for the playing strings and the drone strings. It is raised to allow the sympathetic strings to pass beneath.

Tuning Beads – There are several tuning beads on the sitar. These allow minor adjustments in pitch to be made without having to go the large tuning pegs (kunti).

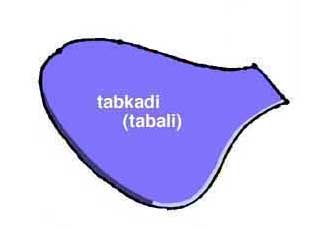

Tabkandi – The tabkandi, also known as the tabali is the face plate. It is extremely important in determining the tone of the instrument. If this is too thin, it will produce a loud sound, but a very poor sustain. Conversely if it is too thick, it will improve the sustain, but at the cost of a weaker sound. It is very important that this wood be clear and consistent. Any knot-holes are a definite weakness in the instrument.

Kaddu – The kaddu is the resonator. This nothing but a gourd. These are extremely delicate and must be protected against shock at all times.

If you would like a more detailed description of the parts of the sitar, check out the Exploded View of Sitar.

Tuning the Sitar

Tuning the sitar is part of the artistic process. Therefore there is no one “standard” tuning which will work for every rag and every situation. Whatever we say in this page must be considered to be just a start from which you can change according to your individual requirement.

In this page we are going to make a simple assumption. We are assuming that you are a rank beginner and are just looking to get your instrument up and playable with the minimum of muss and fuss.

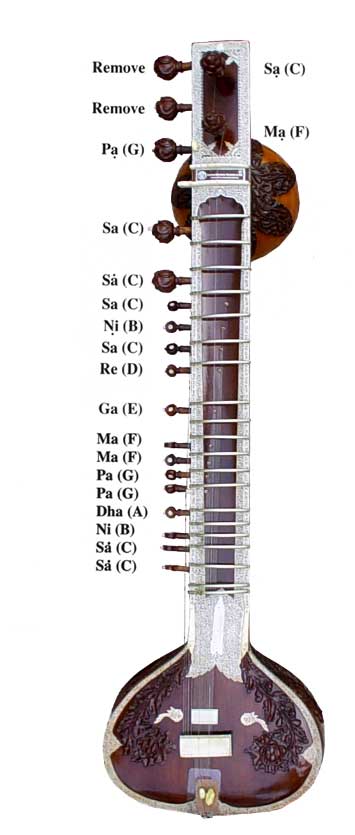

The illustration below is the tuning:

Courtesy of Mel Bay, “Learning the Sitar“

Let us discuss this tuning. By understanding why we are tuning it the way we are, you will understand how to customise it later for different requirements.

The key is one of the main considerations. This particular sitar is tuned to the key of C. Sitars are usually tuned to C, C#, or D. As a general rule, a sitar set to a higher pitch sounds much better. However, we are picking the lower pitch for a simple reason; it is much easier to play.

You will immediately realise that playing a sitar is like playing a cheese slicer. It takes a while to build up the calluses on your fingers, which are necessary to be able to properly play the instrument. By choosing the lower end of the tuning, we have made the sitar much easier to play for a beginning student.

The taraf strings (the ones below the frets) are tuned to the “major” scale. This is presuming that your teacher is starting you off with Bilawal that. In traditional Indian pedagogy it is about 50/ 50 chance as to whether your first exercises will be in Bilawal that or Kalyan that. Should you be learning Kalyan, simply take the Ma strings of the tarafdar (the small pegs on the side) and raise them to F# instead of F.

You will also notice that the strings on two of the pegs have been removed entirely. These are not necessary for a beginner, and are commonly removed. If you do decide to use them, consult with your teacher as to the proper gauge and tuning for your particular style.

Remember all of this is just to get you started. As you progress in your knowledge and experience on the instrument, your tuning will certainly develop into something different.

Playing the Sitar

The technique of the sitar is very involved. It is certainly advisable to have a teacher. However a good introduction to the basic technique is to be found in “Learning the Sitar”.

Making the Sitar

(If this is a topic of interest to you , then you will find the Psychedelic Electric Sitar project interesting.)

This page provides an overview of the making of sitars. One point should be kept in mind; sitar-making is a very individualized craft. Every craftsman is going to have his own individual interpretation. Therefore, the techniques shown here must be considered to be but a sample.

The terms too, must be taken with some caution. India is a land of tremendous linguistic diversity. If a mango is called something different every hundred miles, we certainly expect the names of the parts of the sitar to show a similar diversity. With these points in mind let us look more closely into sitar-making.

The Craft – Sitar-making is a very traditional craft. Many major cities have craftsmen who deal in this commodity. Like the other crafts, it is passed down from generation to generation; in this manner the apprentice learns the techniques form an older, more established craftsman. The one point which continuously comes through is that it is a very manual process.

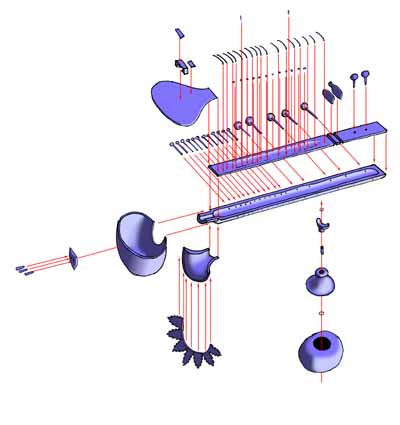

Overview of the Parts of the Sitar – The basic parts of the sitar are shown in the illustration below:

You can zoom in on the previous illustration for a clearer understanding.

Glue, Varnish & Fasteners, and Tools – The tools used are generally simple hand tools. Hand saws, rasps, hammers, and similar tools are the norm. Power tools of any kind are generally not used.

The glues, paints, and varnishes are usually made from scratch.

Glue for instance, is usually saresh; this is a mucilage which comes in brown sheets. It is mixed with a small amount of water and kept over a small fire. There has been a recent introduction of synthetic glues into the craft, but still mucilage is the preferred glue.

There is no varnish as we think of it in the West. The traditional varnish is actually lacquer. Lacquer is a mixture of laq (a tree gum which has been partially digested by insects) and alcohol. Occasionally chandresh is added to give more of a sheen. Paint is made in the same, way except pigment is added to the mixture.

The fasteners are very interesting. Metallic nails have very little use in the craft of making the sitar. Screws are sometimes used. The most common fastener is actually a small tack or nail made from slivers of bamboo. These tacks may be anywhere from 1/4 to one-inch in length. The are made by slicing the outer skin of bamboo. Only the outer skin is used because it is the strongest. In a typical sitar, metal fasteners such as nails or screws can be counted on the fingers; but there are hundreds of these bamboo slivers used. (If your sitar ever breaks the gourd, you can see scores of such bamboo nails on the inside.

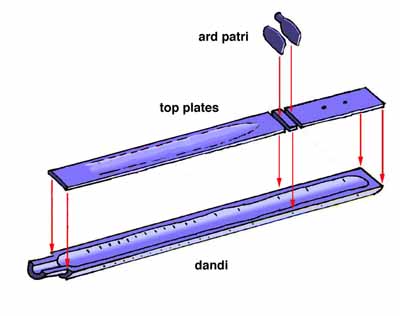

The Neck (Dandi) – The neck is based upon six pieces. There is the major portion of the neck, this is known as daan or dandi. There are three front plates, and two camel bone bridges (ard patri). These are shown below.

The parts of the neck

Patri (Neck Bridges) – The patri are the two bridges at the top of the neck. The word “patri” literally means “leaf” and may be applied to any flat leaf like object. One will find other parts of the sitar also referred to as patri.

Fabrication of the patri is simple. First, rough bridges are fashioned from camel bone. These are shown below:

Patri (upper bridges on neck)

These bridges must then be finished. Cut holes in one of the bridges to allows the strings to pass.&nmsp; The other bridge is notched to allow the strings to pass over them. These is shown in the picture below.

Ard patri in proper place

Taraf Mogara – The taraf mogara are the small grommets made of camel bone that are glued into holes on the neck front plate. They serve to strengthen the hole so that the strings do not bite into the wood.

![]()

Taraf mogara

Gullu – The gullu is the wooden cowl that joins the neck (dandi) with the gourd (kaddu). It is hollowed out of a single piece of wood. This is shown below:

The gullu

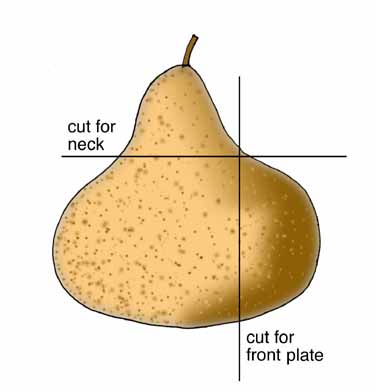

Gourd (Kaddu Ka Tumba) – The gourd (kaddu) forms the bulk of the resonator (tumba). This is a large, hard gourd, roughly 14 inches in diameter. There are two ways that the gourd may be cut and mounted on the sitar. The most common has the base of the gourd running perpendicular to the face (tabkadi). This would be cut as shown below:

Common cut for gourd

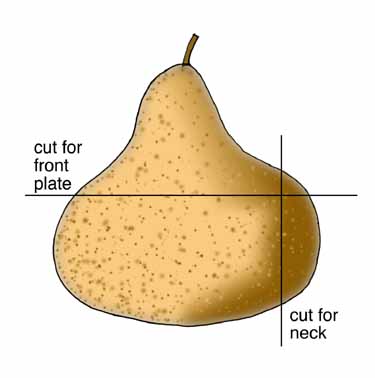

Another way which is sometimes used, is to have the base of the gourd running parallel to the faceplate. This style is considerably less popular. It would be cut in the fashion shown below:

Less common cut for gourd

Tabkadi (Faceplate) – The tabkadi is probably the most important wooden piece of the sitar. It is made from a single piece. It is very important that the grain of the wood run in the direction of the tabkadi. It is also very important that this wood be free of knotholes or other imperfections.

The tabkadi should be neither too thick nor too thin. If it is too thin, the sitar will have a very loud sound; unfortunately it will have a very poor sustain. If the tabkadi is too thick, the instrument may have a good sustain, but a very low volume. If everything is correct, the sitar will have a loud volume and a good sustain.

The tabkadi is shown below:

The tabkadi

Decorative Leaves (Patri) – These decorative leaves are usually made of wood and glued to the gourd, just below where the gullu attaches. They are purely decorative and are sometimes left off the instrument.

Decorative leaves (patri)

Tardani Mogara – The tardani mogara sometimes referred to as kili are the posts where the strings attach to the base of the sitar. The name “kili” literally means “nail” while the term tardani mogara literally means “the jasmine blossoms that hold the strings”. The term kili is so named because the posts somewhat resemble protruding nails, while any of the camel bone protruding bits may be referred to as mogara (Jasmine blossoms). These tardani mogara are fashioned from camel bone as shown below:

Tardani mogara

Wooden Tail Mount – The tail mount is a piece of wood that attaches to the base of the gourd (kaddu). This forms a strong base in which the tardani mogara are placed for the attachment of the strings.

Wooden tail mount with three tardani mogaras

Kunti – The kuntis are the tuning pegs; a sitar has two types. There are larger pegs for the playing and drone strings, and there are smaller ones for the sympathetic strings.

There are three common styles of large tuning pegs. These are the lotus pegs, the fluted, and the simple. These are shown below:

Lotus Kunti – The lotus peg is considered to be the finest peg. The presence of this peg is often a visible indication that the great care was taken for the whole instrument. This is usually found on the professional quality sitars. A lotus peg is shown below:

Lotus kunti

Fluted Kunti – The fluted peg is not nearly as refined as the lotus version. Although one sometimes finds professional quality sitars using this style, it is often an indication of a middle grade of instrument. A fluted peg is shown below:

Fluted kunti

Simple Kunti – The simple peg is often an indication of a student grade instrument. Although there is nothing wrong with this style, it is often an indication that there has not really been a lot of care taken in the fabrication of the instrument. A simple peg is shown below:

Simple kunti

Taraf Kunti – There are also the smaller pegs for the sympathetic strings. An example is shown below:

Taraf kunti

Mogara – The mogara are the two post that raised the chikari strings above the neck. The name “mogara” literally mean “jasmine”. It is so named because the posts somewhat resemble the blossom of the mogara. These posts are placed in holes that are drilled in the side of the neck as shown below:

Mogara

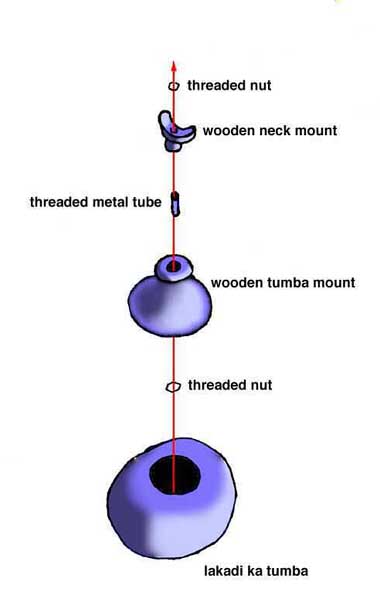

Tumba – The tumba is an optional part of the sitar. It appears to be a relatively recent addition. Even today it is not universal. There are a number of styles. Sometimes it is made of a gourd (kaddu) and sometimes it is made of wood (lakadi). Sometimes decorative leaves are applied (patri). A common method of fabrication is shown below.

The tumba

Opinion is divided as to whether the purpose of the tumba is to affects the sound, whether it affects the balance or whether it is just decorative. It is quite likley that it serves all three purposes.

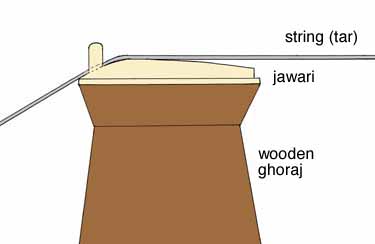

Main Bridge – The main bridge, often referred to as the ghoraj or bada ghoraj, is one of the most unique parts of the sitar. It is composed of two parts. The major portion is wood. However the most critical section is the bone plate, often referred to as the jawari. The preferred material for this plate is antelope horn (barah sinha). However over the years the antelope from which the horns are obtained has become an endangered species. This horn has therefore become hard to obtain. The most common substitute is camel bone. Camel bone produces a material which is surprisingly similar to elephant ivory (hathi ka dant).

The relationship between the wooden bridge, the bone plate, and strings is shown in the figure below.

The wooden bridge (ghoraj), the bone plate (jawari), and the string (tar)

Notice that the bridge has a very characteristic curve to it. This is extremely critical and it takes a lot of experience to be able to produce just the right contour.

Although sanding the bridge to the correct contour is very difficult, the basic concept is quite simple. The bridge works very much like a guitar that has a warped neck. The overtones of the sitar are produced by the rattling of the strings against the bridge.

This has just been a brief introduction to the bridge.

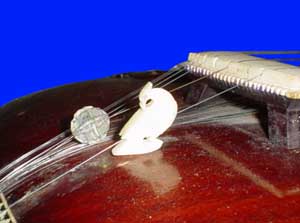

Taraf Ka Ghoraj (Chota Ghoraj) (Bridge for Sympathetic Strings) – The sympathetic strings also have a bridge. This has a contour similar to the main bridge. Both the main bridge and the sympathetic bride are shown in the photo below:

Taraf ka ghoraj (sympathetic string bridge) and main bridge

Parda – The parda are the wire frets on the sitar. They are composed of metallic rods bent to their characteristic shape (see below), and tied with fishing line.

Parda (fret)

Stringing The Sitar – There are a number of approaches to stringing the sitar. The various approaches are inextricably linked to the desired tunings.

When one is stringing the sitar it is usual to have one or more beads to assist with fine tuning of the instrument. A normal bead and a swan-shaped bead are shown in the photograph below:

| This book is available around the world |

|---|

Check your local Amazon. More Info.

|