Introduction

“What is a rag (raga)?” This is a question which comes up very often. In this page we will discuss the rag and explain it in some detail. We will deal primarily with the North Indian approach, but will discuss some elements of the South Indian system as well.

| THESE BOOKS MAY NOT BE FOR YOU |

|---|

A superficial exposure to music is acceptable to most people; but there is an elite for whom this is not enough. If you have attained certain social and intellectual level, Elementary North Indian Vocal (Vol 1-2) may be for you. This has compositions, theory, history, and other topics. All exercises and compositions have audio material which may be streamed over the internet for free. It is available in a variety of formats to accommodate every budget. Are you really ready to step up to the next level? Check your local Amazon. |

The rag is the most important concept that any student of Indian music should understand. Although it is very important, it does not have any parallel in Western music. At the risk of oversimplifying, we can say that it is a mode or a scale to which certain melodic restrictions and obligations are attached.

The etymology of the word is simple. It literally implies “colour” and implies the use of sound as a way colour the mind of the listener.

There are a number of characteristics that a rag must have:

1) There must be the notes of the rag. They are called the swar. This concept is similar to the Western solfege. Like the Western solfege, it is not inherently tied to a key, but will fall into specific pitches as per its use.

2) These notes are arranged into structures known as “saptak“. A saptak is the same thing as the Western gamut.

3) These structure will repeat throughout the audio spectrum. This brings up an alternative meaning to the word saptak which means a register.

4) There must also be a modal structure. This is called that in North Indian music, or mela in Carnatic music.

5) The rag has an internal system of consonance and dissonance. It is derived from psychoacoustic phenomena.

6) There must be a tonic. This is made clear by a drone.

7) There is also the jati. Jati is the number of notes used in the rag.

8) There must be an ascending and descending structure. This is called arohana /avarohana.

9) The notes do not have the same level of significance. Some are important and others less so. The important notes are called vadi and samavadi.

In addition to the above obligatory characteristics, there are other characteristics which may or may not be present.

1) There are often characteristic movements to the rag. This is called either pakad or swarup.

2) Intonation – Occasionally a rag will be defined by a peculiar alteration of the pitch of certain notes.

3) Ornamentation is important in the performance, and in some cases is used to define a rag.

4) Sometimes a rag acquires its definition due to a technical quirk of some musical instrument.

5) Most, but not all rags have traditionally been attributed to particular times of the day.

6) Many rags have been anthropomorphise into families of male and female rags (raga, ragini, putra raga, etc.).

7) The names of the musical terms and names is not consistent. This can be confusing to the music student.

I believe that the vast majority of people will find this brief discussion to be sufficient. But if you really would like more information, we will look at these points in greater detail:

Etymology

It is usefull to consider the origins and usage of the term “rag”. The Hindustani (i.e., Hindi/Urdu) word “rag” is derived from the Sanskrit “raga” which means “colour, or passion” (Apte 1987). It is linked to the Sanskrit word “ranj” which means “to colour” (Apte 1987). Therefore, rag may be thought of as an acoustic method of colouring the mind of the listener with an emotion. This is expressed in the Sanskrit saying, “Ranjayati iti Ragah” (Shankar 1968).

But when did the equation of colour began to be equated with music? In specific, where does rag in the musical sense come from?

The first use of the term raga is traceable to Matang. He was a fifth century music scholar who wrote the Brihadeshi (Menon 1995). Although it is clear that Matang is using the word raga in musical sense, there seems to be considerable doubt as to whether he is referring to raga in the same way that we look at contemporary rags.

There is the thorny question of transliteration. It is variously transliterated as rag, raga, raag, and even raaga; so which is correct? This is not an easy question to answer, for there are two major areas where there can be confusion; pronunciation and the vagaries of the Roman script.

India is a country of many different dialects and languages. Making any definite statement as to how a word is to be pronounced is folly. In general we will concern ourselves with Sanskrit and Hindustani (Hindi/Urdu). In Sanskrit, the last syllable is slightly elongated, therefore when we transliterate this from Sanskrit, we will use the Roman spelling of “raga”. Hindi and Urdu on the other hand will cut this last syllable completely short. Therefore we would transliterate it as “rag”.

There is also the fundamental weakness of the Roman script. The problems associated with attempting to write words phonetically in English need no explanation.

Therefore, the question of “correct” transliteration is but mere quibbling. As is the case with every word from the South Asian subcontinent, a considerable amount of latitude is expected.

Swar (The Notes) & Sargam

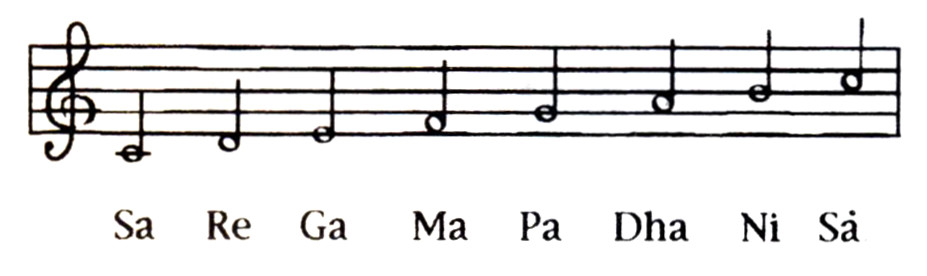

Swar are nothing more than the seven notes of the Indian musical scale. Swar are also called “sur”. At a fundamental level they are similar to the solfa of Western music.

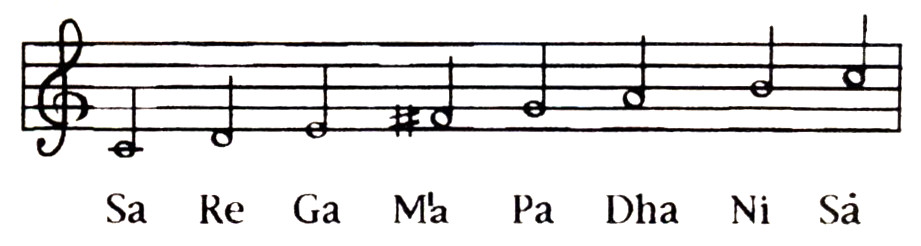

These are shown in the table below. Two of these swar are noteworthy in that they are immutably fixed. These two notes are shadj (Sa) and pancham (Pa) and are referred to as “achala swar”. These two swar form the harmonic anchors for all Indian classical music. The other notes have alternate forms, and are called “chala swar”.

| Indian Swar (Full Name) | Short Name | Western Equivalent |

| Shadj | Sa | Do |

| Rishabh | Re | Re |

| Gandhara | Ga | Mi |

| Madhyam | Ma | Fa |

| Pancham | Pa | So |

| Dhaivat | Dha | La |

| Nishad | Ni | Ti |

Notice that there are two forms of the names of the notes. There is a full version (i.e. shadaj, rishabh, etc.) and an abbreviated version (i.e., Sa, Re, Ga, etc.). The abbreviated name is most commonly used; this is called “sargam“; the term sargam is a contraction of “Sa, Re Ga, Ma”.

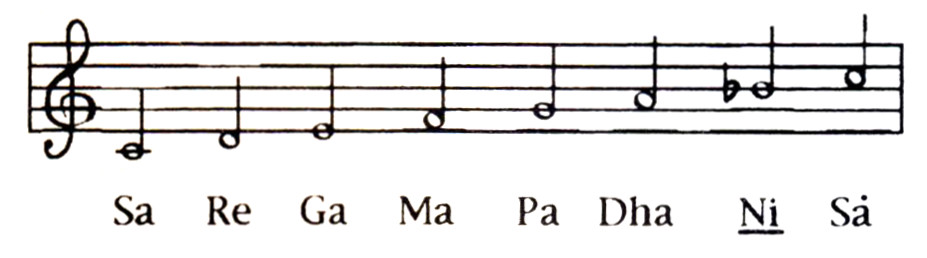

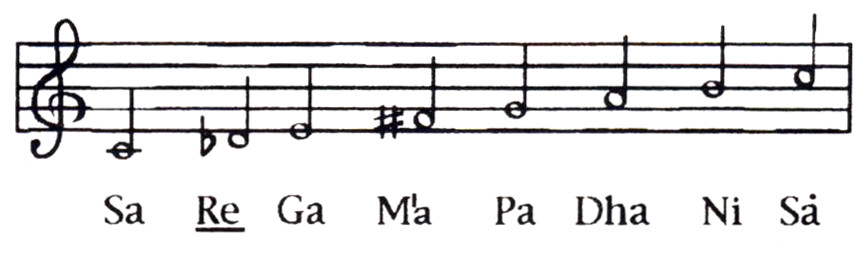

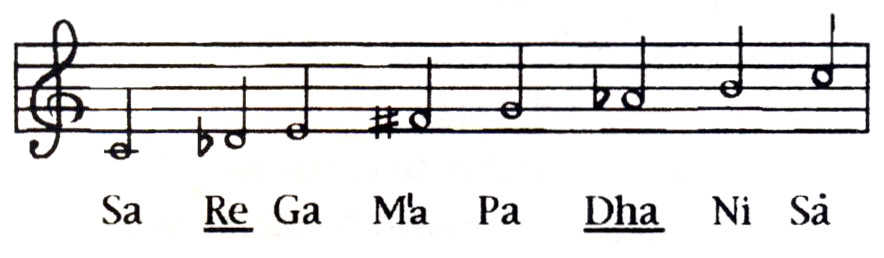

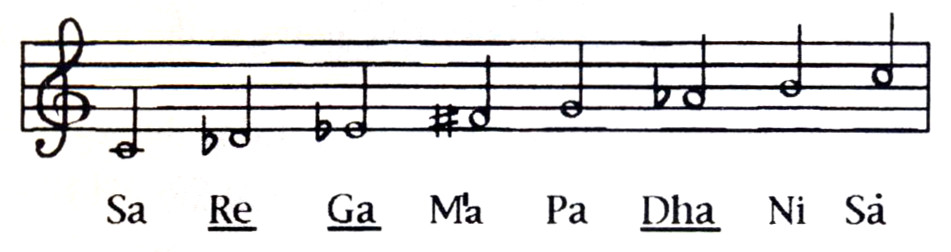

In Hindustani sangeet (North Indian system) the movable notes have two forms. Therefore, the notes; rishabh (Re), gandhara (Ga), dhaivat (Dha), and nishad (Ni), may be either natural (shuddha) or flattened (komal). Madhyam (Ma) is unique in that its alternate form is augmented or sharp. This note is called tivra Ma. Therefore, we find that we are actually dealing with 12 swar. This extended concept is shown in the table below. These are roughly comparable to the keys on a harmonium, or piano (chromatic scale).

The notation of the swar is simple, and lends itself well to the multiplicity of Indian languages and scripts. One merely has to write the short name (i.e., Sa, Re Ga, etc.) for the shuddha (natural ) notes. In the case of komal notes they are underlined. In the solitary case of the tivra Ma, a vertical line is placed above it. (Rhythm, and registers will be discussed elsewhere.)

| Shadj | Sa |

| Komal Rishabh | Re |

| Shuddha Rishabh | Re |

| Komal Gandhara | Ga |

| Shuddha Gandhara | Ga |

| Shuddha Madhyam | Ma |

| Tivra Madhyam | M’a |

| Pancham | Pa |

| Komal Dhaivat | Dha |

| Shuddha Dhaivat | Dha |

| Komal Nishad | Ni |

| Shuddha Nishad | Ni |

The situation in Carnatic sangeet (the South Indian system) is a bit more complex. In the South the movable notes Re (Ri), Ga, Dha, and Ni may occupy one of three positions. Ma however still only occupies two positions, either a natural or augmented position (sharp). This is shown in the table below.

The notation of the swars in Carnatic music is a bit more complicated. Since the notes, Ri, Ga, Dha, and Ni have three forms; they are generally designated as R1, R2, R3, G1, G2, etc.

| Shadj | S |

| 1st Rishabh | R1 |

| 2nd Rishabh / 1st Gandhara | R2, G1 |

| 3nd Rishabh / 2nd Gandhara | R3, G2 |

| 3rd Gandhara | G3 |

| 1st Madhyam | M1 |

| 2nd Madhyam | M2 |

| Pancham | P |

| 1st Dhaivat | D1 |

| 2nd Dhaivat / 1st Nishad | D2, N1 |

| 3nd Dhaivat / 2nd Nishad | D3, N2 |

| 3rd Nishad | N3 |

Western / N. Indian Note Equivalents

This is a chart that shows a correlation between the Western scale and the Indian Swar. We must remember that Indian scales work a bit differently from Western ones in that they are not tied to any particular key. Please also remember that just intonation is preferred over equal temperament.

| A | A# | B | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| A# | B | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| B | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B | C |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B | C | C# |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B | C | C# | D |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B | C | C# | D | D# |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B | C | C# | D | D# | E |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B | C | C# | D | D# | E | F |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| F# | G | G# | A | A# | B | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| G | G# | A | A# | B | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

| G# | A | A# | B | C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# |

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Så |

Saptak (Gamut)

The word “saptak” in Sanskrit means “containing seven”, and is derived from the Sanskrit word “sapta” which means “seven”. (Incidentally, the English month “September” was original the seventh month in the old Roman calendar). Therefore, the saptak is simply a collection of the full seven notes.

Saptak (Register)

The word “saptak” has an additional meaning. Since the seven notes will repeat upward and downward throughout the audio spectrum, this brings up the obvious question as to which saptak one is referring to. Therefore an alternative meaning corresponds to the Western concept of “register”.

In absolute terms, how many registers are there? In engineering circles the audio spectrum is conventionally accepted to extend over 10 octaves. But this is not the way that musicians conceptualise things. In the West, musicians tend to conceptualise the registers as per the piano keyboard. In which case there were typically be considered to be 8 octaves. Therefore a note like “C3” tells us not only the musical note (C), but also which octave on the piano it is to be found (3)

But the Indian concept of octave is different. Unlike Western music, which has an absolute frame of reference, the North Indian system changes from instrument to instrument. The middle register, referred to as madhya saptak, is whatever is most comfortable for that person or instrument; everything else is reckoned from here. Therefore, one register above this is referred to as tar saptak; and the lower register is referred to as mandra saptak. Additionally, two octaves above the middle is called ati-tar saptak; three octaves is called ati-ati-tar saptak, etc. In a similar manner, two octaves below is called ati-mandra saptak; three octaves below is called ati-ati-mandra saptak, etc.

This system is convenient but it does not provide us with an absolute frame of reference. For instance, Sa in the middle register of one instrument could wind up being the Sa of the lower octave of another. One would think that this situation could become problematic, but it never seems to have created a problem in practice.

The register is indicated in traditional notation by the presence or absence of dots. If there is no dot, then the middle register (madhya saptak) is presumed. The dot over a swar indicates that it is tar saptak. Two dots over the swar indicate that it is ati-tar saptak. Conversely, a dot below indicates that it is mandra saptak. Two dots below indicate that the swar is ati-mandra saptak.

That (Mode)

The that (thaat) is the specification as to which of the alternate forms of swar will be chosen. We pointed out that several of the swar have alternate forms. The permutations of the various forms give rise to numerous scales with vastly differing intervals. Therefore the concept of that is essentially the same as the Western concept of a mode.

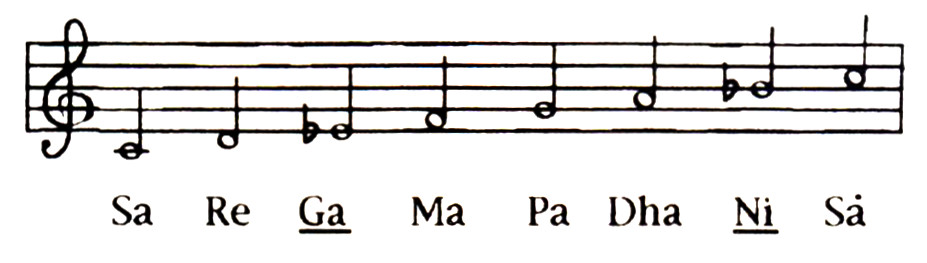

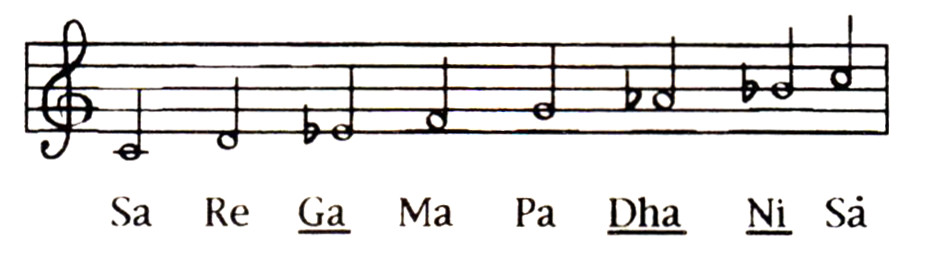

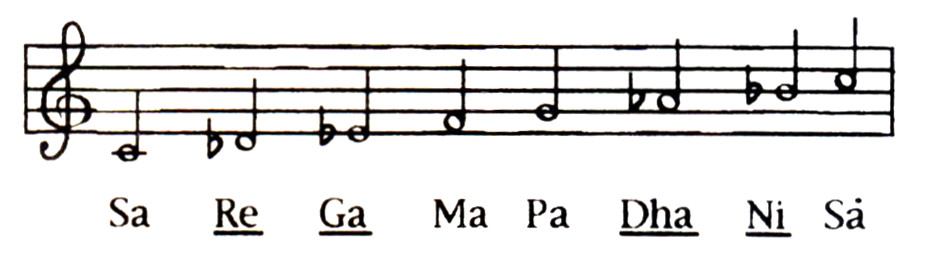

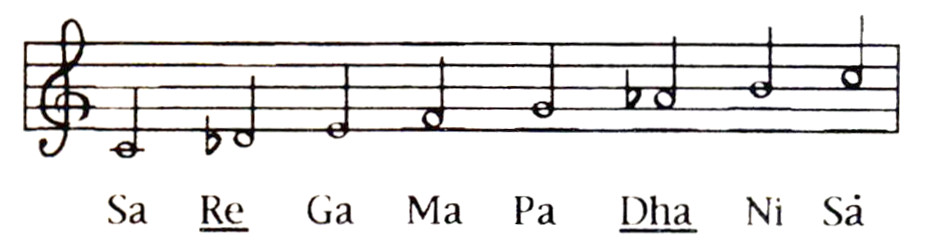

| Bilawal (Ionian) |  |

| Khammaj (Mixolydian) |  |

| Kafi (Dorian) |  |

| Asawari (Aeolian) |  |

| Bhairavi (Phrygian) |  |

| Bhairav |  |

| Kalyan (Lydian) |  |

| Marwa |  |

| Purvi |  |

| Todi |  |

Table of Thats (from “Elementary North Indian Vocal: Vol 1”)

(note – The above notation has been normalised to the key of C. No absolute pitch is implied)

There are problems whenever one is talking about the number of thats. Generally only ten are commonly acknowledged in North Indian music. This goes back to a tradition of pedagogy based upon the work of the early twentieth century musicologist Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860-1936). But even a mid-level student knows that there are very common rags such as Ahir Bhairav, Charukesi, or Kirwani, which clearly do not belong to these ten thats. It appears that in Hindustani sangeet, around twenty are in common usage. If we look at the present concepts of scale construction as they exist in the North Indian system of music, there are 32 possible thats. This has created a lot of confusion in north Indian pedagogy.

Psychoacoustics of Consonance & Dissonance

Consonance and dissonance are two very important concepts which are based upon psychoacoustic phenomena. By its very nature, it transcends culture and goes to the very heart of the way that we hear sound. Therefore, many of the points that we will discuss are common to all music, not just the Indian rag. But as we will see later, the practical expression of which brings us to some interesting points.

The modern scientific approach to psychoacoustics owes its greatest debt to the 19th century scientist Hermann Von Helmholtz (1821-1894). Although individual elements of psychoacoustics have been alluded to by a variety of sources around the world, he was the first to bring the physics of sound, the physiology of hearing, and musical acoustics all together. Research in the last 150 years have clarified or even modified many of his points; but his basic approach remains firm.

It is impossible to go into a complete discussion of a Helmholtzian approach to music in this page. But germane to the discussion of rag is the psychoacoustic foundation of consonance and dissonance.

Consonance and dissonance describe the psychological effect of playing two musical tones together. If two musical tones have a jarring effect (e.g., simultaneously playing Sa and Komal Re), this is referred to as dissonance. Conversely if two notes have a very pleasing and relaxing effect (e.g., Sa and Pa sounded simultaneously), this is known as consonance.

The consonance and dissonance of various note combinations is based upon interactions of their fundamental frequencies and their harmonics. This is a fascinating study in its own right, but one which we will not go into here. However, the relationship of various notes to our tonic (i.e., shadaj), deserves some discussion.

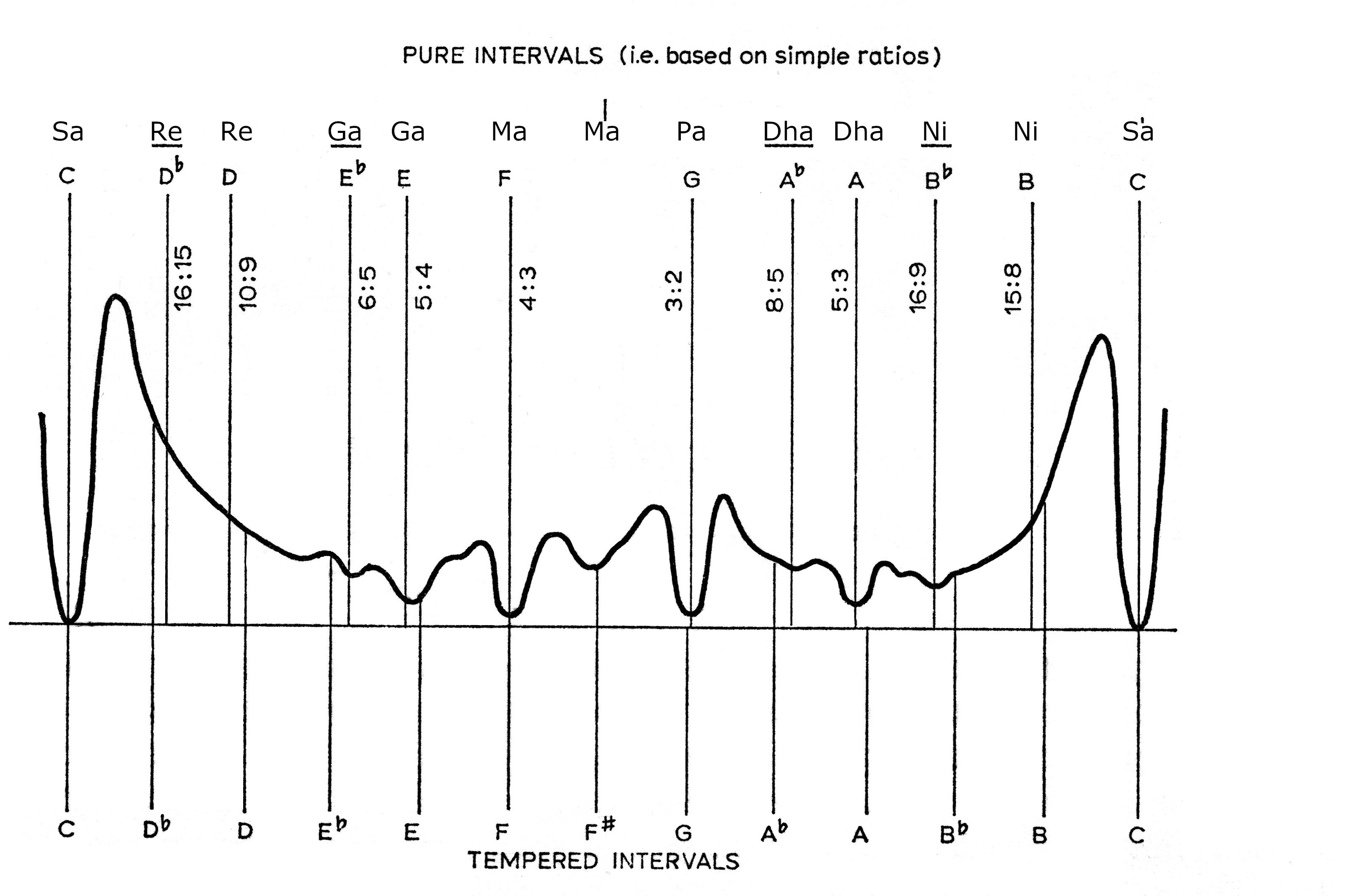

The consonance / dissonance of two tones (e.g., Sa and another note), are of prime importance to Indian music. But consonance / dissonance is not a binary phenomenon for there are numerous shades in between. This is often expressed as the graph below:

According to this graph, the lower value reflects a greater consonance while the higher value reflects dissonance. There are many interesting things which may be seen in the above graph; but the most noteworthy is the extreme consonance of the octave, the fifth (i.e., Pa), and the natural fourth (Ma).

The Tonic

The special relationship shown between the octave, the fifth, and the fourth are reflected in the Indian concept of the tonic. This is very similar to the Western concept; but it is treated differently.

The tonic is the harmonic centre of the scale. Within the Indian system, this is firmly anchored in the Sa. However the Indian concept of the tonic requires there to be a secondary anchor. This is usually Pa, but also quite commonly it is Ma. The psychoacoustic justification for this is firmly rooted in basic concepts of consonance. On very rare occasions this secondary anchor will be something other than Pa or Ma.

It is at this point that the treatment of the tonic in India begins to diverge from Western concepts. In the Occidental approach to music, the tonic may be deduced from the scale structure. However, Indian music is modally far richer than that of the West; therefore a far more direct approach is required. This will be via the drone.

In Indian classical music the modal characteristics are sharply delineated with a drone. At a minimum this will be the solid anchor of the 1st (Sa) and the secondary anchor of Pa or Ma. But on occasion other notes may be added to the drone.

Jati (The Number of Notes in the Rag)

Jati is another characteristic of the rag. The word “jati” or “jaati” literally means a “caste” or “collection”; as such it has numerous musical and non-musical usages. In the musical sense it can mean a rhythmic pattern, an ancient musical mode, or the number of notes in a modern mode. It is this latter definition that we will deal with here.

The number of notes in the rag is significant, for not every one uses all seven notes. Normally, a rag will consist of either five, six, or a full seven notes. A five-note rag is said to be an audhav jati; a six note rag is said to be shadav jati; and one of seven notes is said to be sampurna jati. Furthermore, rags may be mixed jatis (i.e., different jatis for the ascending and the descending structures.) For instance, a rag which has only five notes in the ascending, but all seven notes in the descending, would be called audhav-sampurna.

Arohan / Avarohana (Ascending & Descending Movement)

Arohana and avarohana are the descriptions of how the rag moves. The arohana, also called aroh or arohi, is the way in which a rag ascends the scale. The avarohana, also called avaroh or avarohi, describes the way that the rag descends the scale. Both the arohana and avarohana may use certain characteristic twists and turns. Such prescribed twists are referred to as vakra. Such twisted movements are a reflection of catch phrase or pakad.

Vadi /Samvadi & The Different Importance of Notes

The vadi/samavadi system refers to the varying level of importance of the notes. There was a period when serious scholars ignored he concept of vadi and samvadi. This was because much of its theory was laid down V. N. Bhatkhande in the early part of the 20th century. Bhatkhande’s work was a tremendous advancement in the scholarship of North Indian music. Unfortunately, it acquired an almost dogmatic stature among North Indian musicians. This was problematic in the topic of vadi/samvadi because his system was seriously flawed. However, with the passing of time and the evolution of North Indian rags away from the system Bhatkhande described, scholars have returned to this and other topics and redefined them to bring them in line with current practice. Therefore one can now find relevant approaches to the subject.

The different notes (swar) of the rag have different levels of significance. A note which is strongly emphasized is referred to as the vadi. Another note which is strong but only slightly less so is the samavadi. A note which is neither emphasized nor de-emphasized is called anuvadi. Notes which are de-emphasized are referred to as being durbal; while notes which are excluded are called vivadi.

Some of these are intuitive and need not be elaborated upon. A particular a note which has no particular importance (anuvadi) also deserves no particular discussion. In a similar way, a note which is excluded from the rag (vivadi) is just that, excluded. However a durbal note might be worth a second look, but only to the extent that such notes are either not present in both arohanna and avarohana, or present only in some twisted melodic structure.

Now we can concentrate on the vadi and samvadi. Strictly speaking The terms refer to situations of extreme consonance. That is to say the importance is in how the vadi and the samvadi relate to each other. However in present usage they are used to describe certain melodic anchors of the rag.

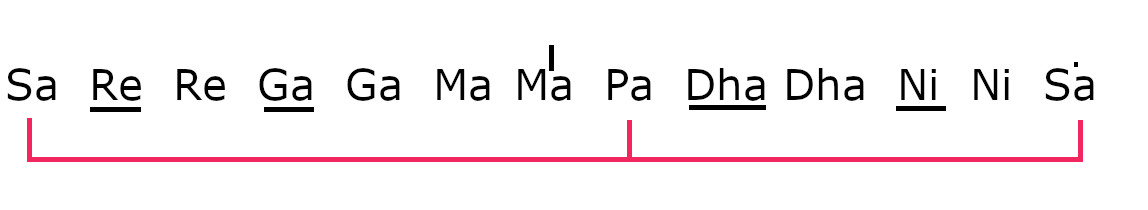

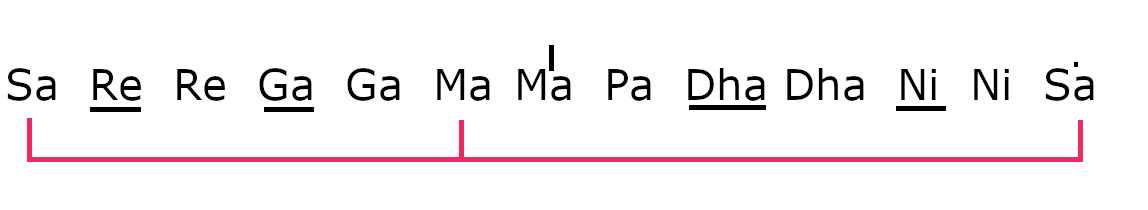

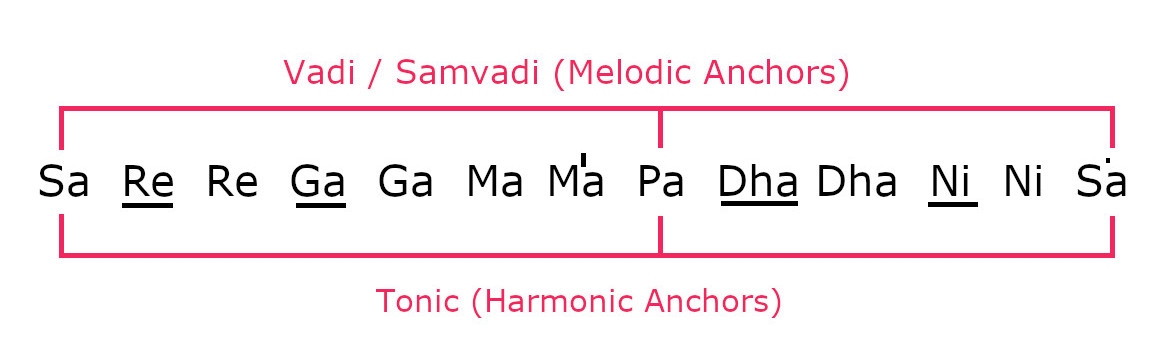

It is appropriate for us to look at what the system of vadi/samvadi is intended to be. Earlier we showed how there was the Indian concept of the tonic which forms harmonic anchors for the rag (i.e., Sa and Pa). But layered over this is another set of anchors; these may be viewed as a melodic anchors. Just as the main harmonic anchors are Sa and Pa, in a similar way the melodic anchors are the vadi and the the samvadi. Just as your harmonic anchors are almost always either a fifth or a fourth apart, in a similar way your vadi and samvadi are almost always a fifth or a fourth apart!

Much of the feeling of the rag is easily explained by looking at the juxtaposition of these two sets of anchors. Let us take the situation where Sa and Pa are both present in a rag and the vadi is Sa while the samavadi is Pa. This is shown in the figure below. A simple Helmoltzian approach to this arrangement shows that such a rag would be steeped in a feeling of peace and repose.

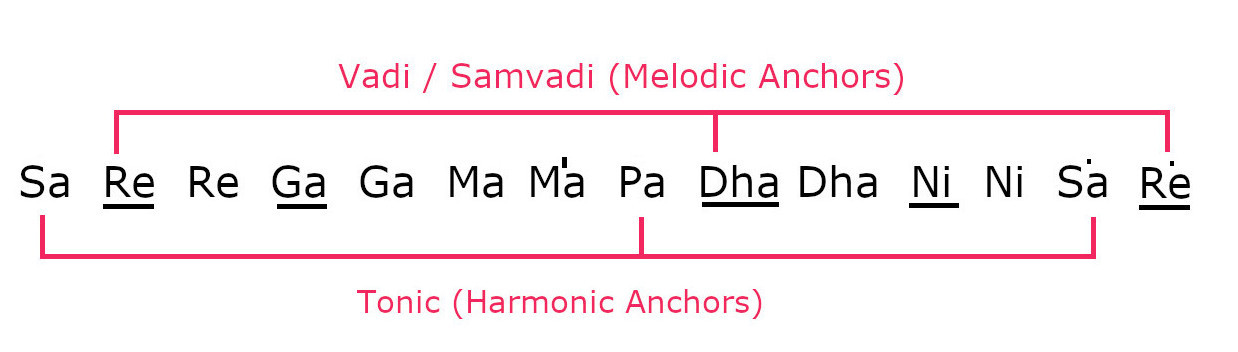

Let us now take a different situation. Let us imagine a situation where there is still Sa and Pa, but now the vadi and samvadi are located a half-step from this. Again a simple Helmholtzian view shows us this rag that would exhibit a tremendous degree of tension.

This is the way that the system of vadi and samvadi is supposed to work; unfortunately these concepts have become corrupted. Consequently it is particularly problematic for the music students today. Musicians never seem to be able to agree with each other as to what the vadi and samvadi of any given rag are. Furthermore, the stated vadi and samvadi often have no bearing as to the actual usages of the notes.

There are undoubtedly numerous reasons for the abysmal situation behind this bit of arcane music theory. But perhaps the biggest culprit lies in the foundational work of V.N. Bhatkhande.

Bhatkhande was a great musicologist and was largely responsible for the development of a workable pedagogical and theoretical system for North Indian music. Unfortunately his original work did have some flaws. His biggest folly revolved around the belief that all rags have a time attached to them, and that this time can be explained in terms of their internal structures. In his efforts to support his cumbersome system, he routinely ascribed vadis and samvadis to rags which in no way reflected their usage. The result was that successive generations of music students have been encumbered by his failed system of vadi and samvadi.

Numerous musicians and scholars over the last century have attempted to rectify this situation. But there is an overall lack of intellectual exchange between practising musicians and academics. This lack of communication continually hampers efforts to develop an accurate and cohesive system for North Indian classical music.

Swarup or Pakad (The “Catch Phrase”)

The pakad or swarup, is a defining phrase or a characteristic pattern for a rag. This is often a particular way in which a rag moves; for instance the “Pa M’a Ga Ma Ga” is a tell-tale sign for Rag Bihag, or “N.i Re Ga M’a” is a telltale sign for Yaman. Often the pakad is a natural consequence of the notes of arohana / avarohana (ascending and descending structures). However, sometimes the pakad is unique and not implied by the notes of the arohana /avarohana. It is customary to enfold the pakad into the arohana / avarohana to make the ascending and descending structures more descriptive.

Sometimes the pakad involves a particular ornamentation. A good example is the peculiar andolan (slow shake) that is found in rag Darbari Kanada. This particular andolan slowly oscillates around a komal Ga which is so low that it is almost a shuddha Re.

Not every rag has a clear pakad. For instance some rags may be defined simply by their mode. This seems to be a growing trend, especially for new rags which are coming into Hindustani sangeet from other sources.

Intonation

Sometimes a rag may use an unusual alteration in the pitch of certain notes (intonation) as a defining factor. Notes may be sharpened or flattened. Rags such as Todi or Darbari Kanada use lower forms of some notes as part of their definition.

Ornamentation

Ornamentation is essential to the proper performance of the rag. When one hears Indian music, it is the ornaments which first make an impression. However, this is a confusing subject. Usually the concept implies a technique which is used for artistic reason, yet not necessarily of theoretical importance. However, there are instances where such ornamentation is a defining characteristic of the rag. In such cases, the ornament becomes part of the pakad.

Let us start with the non-ornament ornament. In a peculiar Zen-like way, even an unornamented note may be considered an ornament. Such a note is called a “khat swar“. However, instruments such as harmonium or bulbul tarang are not able to do anything except khat notes. In which case, a note may be ornamented by quickly touching upon adjacent notes. This produces an effect which is somewhat reminiscent of a vibrato. When affected in this manner, it is often referred to as “khatka“.

Meend is the most common ornament; it is a slide or glissando. Rags such as Shuddha Kalyan and Jaijaivanti use meends as part of their definition. But there are variants upon the meend. One of which is the ghasit; this is an instrumental approach to the meend, which will be described later.

There are also various forms of vibrato. (The vibrato is a modulation of pitch and should not be confused with the tremolo, which is a modulation of volume.) A slow vibrato is known as Andolan. Rag Darbari Kanada is defined by a peculiar andolan where the Ga and the Dha alternate between their komal (flattened) forms and an ati komal komal (ultra flat) forms. The andolan is in contrast to a gamak, which is a much deeper and faster vibrato.

There are ornaments that are specific to instruments. Krantan is an ornament that is a hammering action of the left hand against the fret. It is often used on the sarod or sitar. There is also the ghasit. Where a typical meend on a sitar is affected by pulling the string laterally across the fret, the ghaseet is affected by sliding the finger down the string across multiple frets. This produces a distinctive rattle, and is decidedly discontinuous. However, it is not defined enough to be considered a “run”.

Technical Quirks

Sometimes a rag uses a technical quirk as a defining factor. For instance, if the Pa fret of the sitar is used as Sa for rag Gara, it is known as “Pancham se Gara“. In theory, it should simply be Gara. However, because of the way the sitar is put together, it will not sound the same as Gara played from the usual Sa fret. Hence the designation as a new rag.

Samay (The Timings)

Tradition ascribes certain rags to particular times of the day, seasons, or holidays; this is called samay. It is even said that appropriate performance may bring harmony, while playing at different times may bring disharmony. It is said that the great Tansen was able to create rain by singing a monsoon rag.

There is not a universal agreement as to the correctness of samay. There are some musicians who argue that a rag must be performed at the time of day that it is assigned; conversely, other musicians argue that one may play a rag at any time if one wishes to evoke the mood of that time. For instance, if one simply wished to evoke the mood of a monsoon day, one could perform Megh Malhar; even in the middle of summer.

The concept of samay has other complications. There are a number of rags that have different times ascribed by different musical traditions (gharanas). The concept is further weakened by the influx of rags from south Indian music. Many years ago Carnatic musicians and musicologists abandoned the concept of samay. It seems that it did not fit into their rational, scientific system. The result is that when Carnatic rags enter the Hindustani system, they come stripped of any conventionally accepted timings. The number of such Carnatic rags entering the Hindustani system is very large and constantly growing.

If one is disposed to follow the system of samay, one can only accept that it is merely a question of tradition.

Raga / Ragini (The Mythical Families of Rags)

The concept of families of rags is an interesting aspect of Indian music. Over the centuries rags have been ascribed to certain demigods. A natural consequence of such anthropomorphism is that there be a familial relationship between them. Therefore, in the past few centuries there arose a complicated system of rags (male rags), raginis (female rags), putra rags (sons of rags), etc. This was the basis for a system of classification before the advent of modern musicology.

Although this may have been a great inspiration to the painters of the old ragmala tradition, (see example above) it proved to be worthless as a means of musical taxonomy. The obvious problem was that there was no objective way to accommodate the new rags that were coming into existence. Today the that is the basis for the classification of rags.

Ragmala Painting of Ragini Asawari (reproduction of Mewar school)

Differences in the Names of Ragas

There is always confusion concerning the names of many of the rags. This confusion can result from different ways to transliterate the names; they may reflect different pronunciations within India; or they may be unrelated names that reflect different musical subtraditions.

Transliteration – Transliteration is the process of writing a word in a script other than the one it is normally written in. Transliteration is not to be confused with translation. If a word is translated from Hindi into English, an English equivalent is substituted for the original Hindi. In transliteration, the original Hindi word is used, but is written in Roman script.

Confusion often arises when transliterating the names of the rags because there is not an exact correlation between the Devnagri (ie., Hindi / Sanskrit) and the Roman script. Many times a Hindi / Urdu sound lies between two English letters. For instance there is a sound in Indian languages which lies between a “d” and an “r”. Another example is that the Indian “w” is actually between an English “w” and a “v”. Whenever one runs cross cases where “v”s replace “w”s (e.g., Asawari vs. Asavari) or “d”s replace “r”s (e.g., Gaur Sarang vs. Gaud Sarang) then this may be the cause.

Transliteration is also confused by the fact that the Roman script is not treated in a consistent way across different European languages. For instance, before the turn of the 19th century, most Indian words were transliterated using an imprecise and archaic British approach. However, by the middle part of the 20th century there was a move to adopt a more consistent Germanic approach. This is one reason why many of the transliterations from the 18th and 19th century British travellers seems so awkward to us today.

Different Pronunciations Within India – India is a country with a large number of languages, therefore pronunciations of terms vary. For instance, Vasant is unpronounceable to many people in the North-East part of India; people from these areas tend to call it Basant. In a similar manner, Urdu speakers have no trouble pronouncing Zila-Kafi, which becomes corrupted to Jila-Kafi by most Hindi speakers. Although there are some very easy and predicable ways that such sounds become altered, it is a topic that is more appropriate to studies of linguistics than that of music.

Different Subtraditions – India is a land with many musical subtraditions. Many times a rag will have completely unrelated names. For instance, Ahir Bhairav as often times known as Chakravakam.

Conclusion

The myriad of technical considerations are interesting. They are important to know for any serious musician. But ultimately a rag is like a person. It is a person that you must get to know from a very intimate relationship. Only after such a close personal experience can one perform it.

Selected Video

Works Cited

Apte, Vasudeo Govind

1987 The Concise Sanskrit English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

Bhatkhande, Vishnu Narayan

1934 Srimal-laksyasangitam. Poona. (under pseudonym, Chatur Pandita Visnu Sharma)

1934 A Short History of the Music of Upper India. Bombay, India: reprinted in 1974 by Indian Musicological Society, Baroda.

1993 Hindustani Sangeet – Paddhati (Vol 1 – 4): Kramik Pustak Malika. Hathras: Sangeet Karyalaya.

Jairazbhoy, N.A.

1971 The Rags of North Indian Music: Their Structure and Evolution. Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Menon, Raghav R.

1995 The Penguin Dictionary of Indian Classical Music. New Delhi, Penguin Books.

Shankar, Ravi

1968 Ravi Shankar: My Music, My Life. New Delhi, India: Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd.