| ABSTRACT The tawaifs were an Indian equivalent of the Japanese Geisha. Their heyday was in the 18th and the early 19th century. They were very important in the development and propagation of a number of North Indian styles of music and dance, most especially the kathak form of dance, and the thumree, and dadra forms of singing. However, after the British consolidated their control over India in the last half of the 19th century, the tawaifs were branded as prostitutes, and subsequently marginalised in society. This marginalisation might have proved disastrous for their arts, had it not been for the intervention of the Indian bourgeoisie at the turn of the 20th century. The “rescue” of the tawaif’s arts was remarkable, but was accompanied by an extensive degree of recontextualisation in order to fit them into the emerging culture of Post-Independence India. |

Part 1 – Introduction

The anti-nautch movement was a movement in the late 19th century and early 20th century to abolish the traditional Indian dancing girls. This movement was started by the British, but carried out with the assistance of numerous Indians and Indian organisations. The consequence of this movement had profound impact on the well being of Indian dancers, musicians, and singers throughout the subcontinent. Although a number of artistic traditions were impacted by the anti-nautch movement, it is the north Indian tawaif, along with their accompanying musicians, which will be the major focus of this webpage.

The tawaif was a member of a courtesan class. Kamal’s Oxford Advanced Illustrated Dictionary defines tawaif (तवायफ़) as “prostitute, harlot” (Kapoor, undated). This definition reflects common misconceptions and usage, but it is very far from the complex historical reality. They were somewhat analogous to the Geisha tradition of Japan.

What Will be Discussed Here – It is appropriate for us to discussed what will and will not be coverted in this article.

We will be looking at several topics in this article. We will briefly look at the tawaif tradition. We will concentrate on the political and social events leading up to the anti-nautch movement. We will look at the movement in full bloom; and also briefly look at how this movement, along with the general cultural renaissance of the period, influenced the development of north Indian classical music.

But the specifics of the tawaif tradition itself will only briefly be touched upon. There will be a brief discussion of their arts, and a small discussion of a few famous tawaifs. This will be discussed only to the degree necessary to have good grasp of the topic. But the rise of the institution of the tawaif, the different classes of tawaifs, and their social structures, are beyond the scope of this article.

We will also spend very little time on the devdasi (देवदासी). There were major differences between the devdasi tradition of South and East India, and the tawaif tradition of the North and North-West. The devdasi is certainly a very worthy topic for study, but it too, is beyond the scope of this modest web page.

We will try and maintain a focus on the tawaif, but at times this is difficult. The anti-nautch movement ran willy-nilly through India’s complex social fabric, effecting common dance girls (nachwali – नॉचवाली), devdasis (temple girls), common prostitutes, and a tawaifs alike. We will continually be pulled outside of the focus of this article in our attempts to track this movement. Your understanding and indulgence in this matter is solicited.

It is very important to remember two points. In order for the British to carry out the anti-nautch movement there were two things. First, there had to be a will to carry out this movement; and second, the British had to have consolidated their control over the Indian subcontinent to the degree that they could actually carry it out. Therefore, a substantial amount of time will be devoted to these points.

Now that we have a roadmap as to the topics that we will be discussing, we can proceed.

Delhi tawaifs prepairing for a dance (circa 1830)

A Few Terms -There are a few important terms that must be understood. In particular we must be familiar with the terms “tawaif”, “nautch”, “kotha”, and “devdasi”.

The word “tawaif” is a word rich with emotional connotations. The term “tawaif” is the plural form of the Arabic “Taifa”, and as such meant “group”. Today the term has become synonymous with a prostitute. Unfortunately, this is an extreme corruption of the word, and not at all a reflection of this once noble institution.

Kashmeri tawaifs with a hookah. (circa 1854)

The tawaifs were female entertainers. They were in many ways similar to the geishas of Japan. They excelled in the arts of poetry, music, dancing, singing, and were often considered to be the authority on etiquette. By the 18th century they had become a central element in polite, refined north Indian culture. However, their sphere of entertainment also included entertainment of the more erotic variety; it was the latter activity that contributed to their downfall.

“Nautch” is another term that needs to be discussed. Nautch (नॉच) is an anglicised form of the Urdu/ Hindi “nach” (नाच), which is derived from the term “nachna” (नाचना) which means “to dance”. However, since the 19th century, the term “nautch-girl”, “nach-wali”, or “nautch-wali”, has been indiscriminately applied to tawaifs and devdasis. Please also note that for these articles we will be using the Victorian English corruption “nautch” instead of the more current and academically acceptable “nach”. This is done to maintain the Victorian feel.

The confusion of “tawaif” with “nautch-wali” is due to a mixture of ignorance and half-truths. It is correct that dance was a major portion of the tawaif’s accomplishments; but every tawaif was not necessarily an expert in dance, nor was every dancing girl necessarily a tawaif. Still from the standpoint of the zealots who were engaged in the anti-nautch movement, the terms all represented a prostitute.

Picture postcard depicting a “nautch-wali” along with tabla and sarangi (circa 1900)

Another term to concern ourselves with is the “devdasi”. The term “devdasi” literally means “a female servant of God”. The devdasis were girls who were attached to the temples. It is important to remember that there was virtually no connection between the devdasis and the tawaifs.

Finally the term “kotha” काठा should be examined. The word kotha implies a multi-storied house or mansion, specifically one which is built with bricks or stone inhabited by the tawaifs. The implication was that it was the place where the tawaifs lived. However, it assumed a different significance. One sometimes encounters the phrase “kotha culture”, which encompasses the entire culture of the tawaif; this includes the entire circle of patrons, poets, musicians, and artists. The word “kotha” is linguistically linked to the word kothari (literally a small kotha or a cottage), and kothi (a mansion). It is also interesting to note that from an architectural standpoint, “kotha” and “kothi” mean the same thing; however the word “kothi” often invokes the connotation of a bank or a royal dwelling, and seems to have no connection with the tawaifs.

Architectural example of an old kotha / kothi

The kotha was not just a building, but an institution. The cultural importance is well known. However, it was of great economic importance as well. Wherever a kotha was established, markets would spontaneously spring up around them (Arfeen, 2016)

Part 2 – The Tawaifs – An Overview

The Tawaifs at their Height – The tawaifs became very prosperous and influential during the Moghul period, but continued to enjoy wealth and political power even after the Moghul empire devolved into a number of autonomous principalities. (1)

The zenith of the tawaif stretched from the 18th century to beginning of the 19th century. It is difficult to put an exact date on this, but it is safe to say that their heyday started at the end of the reign of the Moghul emperor Aurangzeb (Majumdar, 1972), and ended with the suppresion of the Uprising of 1857.

The tawaifs depended upon royal patronage for their support; in this regard there are numerous examples. The tawaif Lal Kunwar was the queen and wife of the Moghul emperor Jahandar Shah (1661 – 1713) (Nevile 1996). The Moghul emperor Mohamad Shah Rangila (1702-1748) also married the tawaif Uttam Bai (later known as Qudsia Begum)(Nevile 1996).

Even the decline of the Moghul empire did not adversely affect thepatronage of the tawaif. One of the most famous examples of lavish patronage was the court Wajid Ali Khan in Lucknow (Nevile 1996). Another example is the Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780-1839) of Punjab who maintained a bevy of 150 dancing girls selected from across northern India.

Activities – The tawaif was inextricably linked to the aristocracy of Northern India. In return for financial support, the tawaifs maintained the art and culture of the area. They specialised in singing, dancing, poetry, and the erotic arts. Furthermore, they were considered to be the absolute authorities on etiquette, and the social graces. Since they were freed from many of the mundane duties of ordinary women, they were able to elevate these artistic activities to levels that most men could never attain. It was normal for nobility to send their children to the tawaifs to be instructed in the arts and letters.

The tawaifs were considered to be the originators, or at least the popularisers, of several art-forms. For instance, the vocal forms of the dadra (दाद्रा), ghazal (ग़ज़ल), and thumree (ठुमरी) were their speciality. In particular, the kathak (कत्थक) form of dance is inextricably linked to the tawaif. This highly rhythmic, and at times abstract form of dance, has been popular in northern Indian for centuries.

There were also areas that they generally did not delve in. Obviously menial work was out of the question. But it is interesting to note the musical fields in which they seldom indulged. Although they would occasionally play musical instruments, being an accompanist was beneath their dignity. They would usually hire men to play the accompanying instruments such as tabla and sarangi; the status of these musicians was definitely that of “hired help”. (Please note that we do not make any mention of the harmonium. This was not invented until the second quarter of the 19th century, so we will discuss this later.)

The dignity of the tawaif may have prevented her from stooping to lowly professions such as playing a musical instruments, but their dignity empowered them at times to acquire massive wealth, political power, and even military might. This will be illustrated as we take a brief look at some famous tawaifs.

Part 3 – A Few Famous Tawaifs

The accomplishments of many of the tawaifs would be the subject of a whole book. Obviously we are unable to give a full treatment to the subject here, however a cursory overview of some famous tawaifs will give an indication of the great heights to which many of them attained. Aside from the previously mentioned dancing girls, here are a few tawaifs who gained great political power.

Begum Samru (circa 1753 – 1836) – Begum Samru was a tawaif, who arose to become the ruler of the principality of Sardhana. As a very young girl, she came to live with a European expatriate by the name of Walter Reinhardt Sombre. He was leader of an mercenary army comprised of both native as well as European soldiers. Upon his death, she assumed command of this army, and by means of her extraordinary political, and military abilities, became the ruler of Sardhana. She enjoyed this position until her death in 1836.

Begum Samru

Moran Sarkar – Moran Sarakar was a tawaif who rose to become Queen. She became the wife of the Maharaja Ranjit Singh (a.k.a. “The Lion of Punjab”)(1780-1839) in 1802. She was considered to be very learned in the arts and letters, and was respected for her philanthropy. It is interesting to note that even though Maharaja Ranjit Singh never minted a coin with his own image, he did mint coins with her image.

Moran Sarkar

Umrao Jaan – It is impossible to discuss the tawaifs without mentioning Umrao Jaan of Lucknow. Unfortunately the various films and novels have taken such artistic liberties with her life, that she exists more as a legend than an actual person. We know for sure that a tawaif by the name of Umrao Jaan existed, but that is about all that we can be certain of. The only details of her life come through the “Umra-o-Jaan-e-Ada”; this was a novel written in 1905 by Mirza Mohammed Hadi Ruswa. Undoubtedly artistic liberties were taken in the book, with the result that we are just unable to tell fact from fiction. Therefore it is probably better if we exclude her from further discussion.

Rekha in 1981 film adaptation of Umrao Jaan

Final Overview of the Tawaif – When everything is considered about the tawaif, an interesting picture emerges. The tawaifs had options open to them that were generally denied women of a more domestic nature. If they had professional aspirations, especially in the artistic fields, they had a virtual monopoly. If they desired to settle down, marriage was always an option. From what we know of history, when this option was taken it was often with only the wealthiest and most well placed men. Remember their mastery of etiquette and the social graces made the tawaifs a “prize catch”, for almost any man. If they desired an independent lifestyle, this too was an option which the tawaif could exercise that was denied most women of the period. This is born out by an examination of tax rolls that tend to show only tawaifs as female property owners and tax payers. The tawaifs were often poets and authors, in a period when the majority of women were illiterate. When everything was considered, the tawaifs had, education, independence, money, power, and self-determination, in a period when many women were little more than cattle.

Part 4 – Evolution of the Will to End the Tawaifs

For the various groups to eradicate the tawaifs, it is very obvious that there had to be two conditions met. First, there had to be a will to eradicate the tawaifs. Secondly, there had to be the capacity actually do so. The “will” to eradicate the tawaif sprang from numerous sources. These included political, cultural, Christian evangelical, and personal reasons. However, the major motivation came from the rise of the Social Purity movement and its transplantation into the Indian subcontinent. This will be the major topic of discussion for this section.

Rise of Evangelicalism – The 19th century was a time of rising Christian evangelicalism in Great Britain. The combination of evangelism, evangelicalism, and imperialism would have dire social, political, and economic consequences for much of the world. There were two periods of religious revivalism that share responsibility for the anti-nautch movement. These two movement are often referred to as the “The Second Great Awakening” (1790- 1840’s) and the “Third Great Awakening” (1880-1900).

The “Second Great Awakening” swept Great Britain during the early part of the 19th century. This was responsible for creating the structure that would be used for the anti-nautch movement. Most notably it was the pressure of the evangelical Christians upon the British Parliament that that created the Missionary Clause in the 1813 renewal of the East India Company’s charter. This clause opened up India to missionary activities. It was the increased presence of these missionaries that would prove crucial to the execution of the anti-nautch movement several decades later.

There was another wave of religious revivalism that spread through Great Britain from about the 1880s through the first decade of the 20th century. Some refer to this as the “Third Great Awakening” but there is not a great agreement as to this term; Some suggest that this is merely an extension of the “Second Great Awakening”. Regardless of what we wish to call it, this was the wave that was actually responsible for the anti-nautch movement. By the time this revivalism set in, the presence of Christian missionaries was well established in India. Furthermore, the control over the Indian subcontinent was substantial. Therefore, when these missionaries somehow decided that watching Indian dance would bring destruction to the moral fabric of India (Nevile 1996), they were well placed to carry out their persecution.

Social Purity Movement – The anti-nautch movement in India is inextricably linked to the rise of the social purity movement in Great Britain. Therefore, it is necessary to have some understanding of this movement in order to gain a perspective on the anti-nautch movement.

As is typical of most social phenomena, the social purity movement represented the outcome of a number of different concepts, theories, conceptions, and misconceptions of the era. In other words, it was inextricably linked to the zeitgeist of the 19th century. In this case, we will see that it was a logical outgrowth of a growing Christian puritanical movement, supported in part by scientific hypotheses which have since been discounted.

The “scientific” basis of social purity was summed up by Max Nordau’s (1849-1923) concept of “degeneration”. According to this theory, a preoccupation with gambling, alcohol, sex, and the other vices as defined by the Christian churches, led to a decay of the central nervous system. Such decay in turn led to further indulgence and licentious behaviour, which again leads to further neurological decay. According to the Lamarckian theory of evolution that was popular at the time, such “degenerate” characteristics would be transmitted to the next generation. The cascading nature of degeneration would inevitably lead to a breakdown of all civil society. It was clear that in order to save society from this dire fate, it was essential that such vices be eliminated. Among the myriad of vices that society was prone to, the sexual vices were considered the most serious.

In the 19th century, a number of social purity organisations arose in great Britain. These were the National Vigilance Association, the White Cross Army, The Salvation Army, The Church of England Purity Society of the White Cross League (CEPS), and a host of others. These groups would roam the streets and harass, attack, or cause the arrest of any man or women that was engaging in activities that they deemed to be immoral. The pursuit of prostitutes, and men patronising prostitutes, seemed to be their main activities.

Women of the Salvation Army

Today, it is easy to dismiss the degeneration theory and the social purity organisations. However, we must remember that the people who lived in the 19th century were not stupid; they just lived with a different set of conditions and world views. The scourge of neurosyphilis and tertiary syphilis were painfully clear to them, as were the effects of alcoholism, and opium addiction. The near absence of safe, effective treatments, meant that Victorian Europeans were left with no alternative other than the social, preventive ones. This partially explains the support that the social purity movement was receiving even from people who were not religious zealots.

Tertiary effects of syphilis

We have seen how the social purity movement provided the major impetus for the anti-nautch movement. But this was not the only factor.

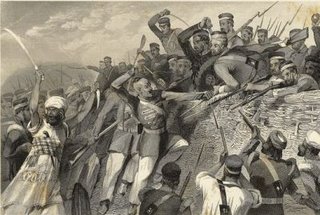

Political Considerations – For many people, the elimination of the tawaif had political considerations. Just as the Masonic lodges acquired the reputation for being centres of sedition in the American Revolutionary war, and coffee houses acquired the reputation for being the places where the Russian revolution was hatched, in a similar manner, the kothas of the tawaifs had the reputation of being behind the Uprising of 1857.

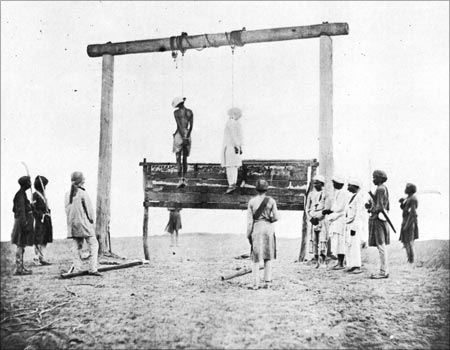

Uprising of 1857

This uprising was definitely a notably event in both Indian history as well as British History. This event is variously referred to as the “Indian Rebellion of 1857”, the “First War of Independence”, the “Great Rebellion”, the “Sepoy Mutiny”, and a host of other names to suit your particular political persuasion. Years of British presence and meddling in the local political affairs, resulted in a great deal of resentment among the local population. After the annexation of Awadh (Oudh) in 1856, tensions were running especially high. Northern India broke out in rebellion in 1857. This uprising was suppressed in 1858.

The connection between the kothas of the tawaifs and the uprising is well known. From the earliest days, the close social interaction between the tawaifs and the feudal lords, meant that tawaifs were no strangers to court intrigues. It was only natural that in the 1850’s, these same kothas should be centres of political debate, some of which resulted in the Uprising.

After the Uprising, the British retaliated against the tawaifs. Many had their property seized. Many zoning laws were enacted that adversely effected them. When the anti-nautch movement started in the late 1800s, this not so distant piece of history could not have been forgotten.

Other Motivations for the Elimination of the Tawaif – There are further reasons which may have provided some motivation for the elimination of the tawaif. These include cultural chauvinism, and simple jealousy on the part of British women. Although the social purity movement appears to be the strongest motivation for the elimination of the tawaif, with political considerations a distant second, we must not discount these other forces.

Cultural chauvinism must be considered when we search for other motivations to eliminate the tawaif. The British who lived in India at the end of the 19th century were convinced that European culture, especially English culture, was the absolute pinnacle, and that any other culture was automatically inferior. The tawaifs represented a major reservoir of Indian culture. Therefore in the British mind, the tawaif represent a form of cultural “degeneration” that, like the more physical forms, must be eliminated.

One other reason which certainly must have been considered by some British, especially the British women living in India, was the potential threat posed by the tawaifs. Toward the later part of the 19th century, improvements in transportation, coupled with improvements in public health (at least in the British cantonment areas), made India much less hazardous. The result was that there was a substantial rise in the number of British women living in India. The presence of the tawaif could not help but be viewed as a competition for the amorous attentions of their men folk. After all, the presence of the Anglo-Indian community stood as a silent testament to this sort of thing.

British memsahib in India

We have already said that in order for the anti-nautch movement to be successful, there had to be both the desire to eliminate the tawaif as well as the the ability to do so. We have discussed at great length many of the reasons which created the desire to eliminate them. Now we must look at many of the events which lead to the ability to eliminate the tawaif. In the next section we will look into many of the events which empowered the British to eliminate the tawaif.

Part 5 – Evolution of the Means to End the Tawaifs

It is clear that in order for there to be a functioning British lead anti-nautch movement in India, there had to be a significant British presence in India. By significant, we really mean two things. First the number of British in India needed to be sufficiently high that they could affect this sort of thing. Secondly, they had to have a military, social, and administrative framework with the capacity to do so.

The British presence at the end of the 19th century was very different from what it had been a century earlier. It is clear that a century earlier, the British could not have executed an anti-nautch movement. So what were the events which altered this presence in India. It turns out that there was a fundamental shift in administrative philosophy. This change in the British approach towards India, coupled with general improvements in technology and transportation, gave Britain the where-with-all to consolidate its control over India. This section will chronicle Great Britain’s ever tightening control over India in the 19th century.

Orientalist / Anglicist Debate – There was a major debate in the 19th century as to how the British were going to administer the Indian subcontinent. There were basically two factions. One group was the “orientalists”; this group maintained that local traditions, languages, and political structures should be used and manipulated as much as possible for an effective control of the subcontinent. The other group were the “anglicists”; this group held that India should be administered along a strictly English model. According to the anglicists, India should be moulded and changed to reflect British standards and mores. In the beginning of the 19th century, India was administered by an orientalist approach; however by the end of this century, the approach was solidly anglicist. Let us look at the various events which brought such a fundamental change in administrative philosophy.

Orientalism – In the early days of the East India Company, the predominate philosophy was orientalism. Their approach was to quietly insinuate themselves into Indian society. Once there, the British manipulated the subcontinent by a complex system of treaties and agreements. They frequently set one principality against another, thus weakening both parties in the process, and then extracted whatever lands, rights, or treaties that they desired. In short, the British generally relied upon subterfuge and stealth to obtain their desired objectives. They only resorted to military intervention when other methods failed. The orientalist approach was deemed to be very successful because it allowed a very small number of British to effectively control the entire Indian subcontinent.

Orientalist official of the East India Company (circa 1760)

Seeds of Anglicism – The first sign that things might change came in the late 18th century. This was when many in Great Britain were questioning the East India Company’s official resistance to missionary activities. Great Britain was in the grips of a great religious wave of fundamentalism that has come to be known as the “Second Great Awakening”. Many in Great Britain viewed India as being a heathen land, and that merely making a profit was not enough. They considered it their “Christian duty” to add evangelism to the list of activities to which the East India Company should be involved. Although the more pragmatic members of the company strongly reject this proposition, the power of the evangelicals increased. 1813 was a turning point in this regard, for it was in this year that Parliament renewed the charter of East India Company, but attached to this was a clause guaranteeing Christian missionaries access and freedom to work in India.

For a number of years the East India Company continued its operations. As a matter of practicality, the orientalist approach was still the the prevailing philosophy. But the seeds of anglicism had already been sewn.

Ascendency of Anglicism – The Anglicists did not stay in the background very long. Events came to pass that suddenly thrust the them to the fore, and relegated the orientalists to history.

Orientalism was called into question by the the Uprising of 1857. This uprising was viewed in Great Britain as a sign of failure of Orientalism; they claimed that a totally different approach was necessary, and that a more hands-on approach was necessary. The East India company’s holdings came directly under the crown in 1858, at which point the East India Company effectively ceased to be any relevance in Indian affairs.

Now that the anglicists had control of the subcontinent, they embarked upon one of the most ambitious projects of social engineering the world had ever seen. Led by Lord Macaulay and a host of Anglicist minions, they set about to remake India along the lines of Great Britain. (2)

Lord Macaulay

The churches and other entities dutifully took over the major job of setting up schools where bright young Indian lads were educated. The education in these school revolved around academic subjects that were all according to British standards.(3) Their graduates were duly taken up and given employment in the various British establishments, thus creating a whole new “babu” class.

The mindset of this Indian bourgeoisie was complex and not at all homogenous. We must remember that it was from this class that the independence movement emerged. But in the 19th century, the majority embraced the Victorian attitudes of the day. As we will see, this would have dire consequences for the tawaifs, for they would join with their imperial masters in the coming anti-nautch movement.

Part 6 – Why Did Britain Do This?

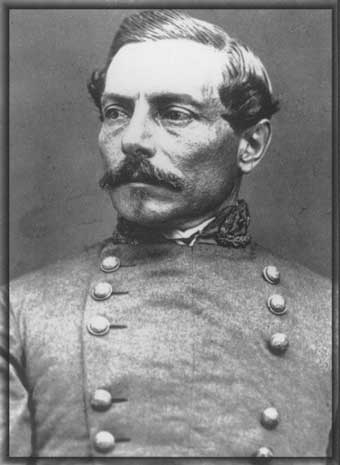

It is clear that such a massive undertaking required a tremendous amount of resources. One would naturally question why England would be willing to invest these resources in an area on the opposite side of the globe. The answer to this very fundamental question was that Great Britain did not have a choice. It had become an absolute imperative due to a complex series of events occurring in a totally different part of the world. These events cascaded like dominoes from a decision made by a man by the name of Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard.

Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, leader of Confederate troops in Charleston

This chain of events worked like this. Beauregard was a Brigadier General in the Confederate States of America, in control of soldiers in the City of Charleston, South Carolina. In Charleston harbour, was Fort Sumpter, which was occupied by the United States. On April 10, 1861, General Beauregard ordered the American forces to surrender the fort. On April 12, when they refused, Beauregard ordered the Confederate forces to open fire. This officially started the War Between the States. The escalation of the US Civil War proceeded in a fashion that is well known to many people today. However of particular significance to this article, was the blockade of southern ports by American navel ships. This began on April 19th, just a few days after the fall of Fort Sumpter. Although this blockade had only a limited effect initially, it grew until the Confederate States of America were totally cut off from Great Britain.

At this point you are no doubt wondering what the American Civil war had to do with India and tawaifs. As it turned out, it had everything to do with it. We will see that this was one of the major reasons why India became so important to great Britain’s economy. It became so important, that Great Britain really had no choice but to invest considerable resources to consolidate its control over the Indian subcontinent. This entire situation, complete with its imperialistic implications, can be summed up in a single word – cotton!

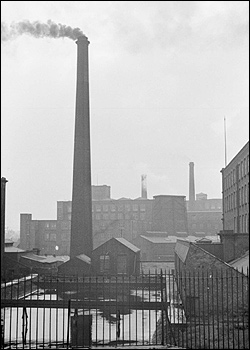

By the middle of the 19th century Great Britain was producing half of the world’s cotton textiles. A single British mill known as the Quarry Bank Mill in Cheshire accounted for 0.6 percent of the entire world’s production alone! Yet Britain produced absolutely no cotton agriculturally. Therefore, Britain was completely at the mercy of foreign markets for its supply of raw cotton. In particular it was dependent upon three countries, the US (Confederate States of America), Egypt, and India.

English Textile Mill

The American Civil war was having a devastating effect upon Great Britain’s textile industry. The disruption in the supply of cotton, meant that Great Britain’s textile mills were only functioning at a fraction of their normal capacity.

There were only two other countries that were left to supply cotton to Great Britain. One of these was Egypt and the other was India. Egypt was not under British control, so it was immediately recognised that Britain should not become dependent upon it. India had just recently come under the crown, so there really was not much debate in the matter. India had to be consolidated into the empire, even if for no other reason than to keep Britain’s textile industry viable. A major financial investment in India was not merely an option; the British textile industry absolutely demanded it. The British empire functioned like one giant imperialistic machine; and India was a major component of this giant machine.

Part 7 – The Oil of the Machine

We invoked the metaphor of a great imperialistic machine to describe India’s position in the British empire. If we push this metaphor a bit further, there were a number of developments which may be view as the “oil” of the machine. These were a number of, inventions, and events, which made the machine possible. At first some of these points may seem unimportant, but just as a mighty machine can be brought to a grinding halt by an absence of oil, it is entirely possible that if any one of these events had not happened, the British consolidation of India might not have occurred.

Cinchona, Quinine, and Malaria – In the early days of the East India Company, relatively few British came to India. The large number of diseases endemic to the subcontinent took a major toll. Of all the diseases endemic to the India, malaria had a special significance. Deaths frequently occurred from a sort of “one-two-punch.” In this scenario, one would contract malaria. Although death from malaria itself was not very common, it was a very debilitating disease. Therefore, once a person was weakened by malaria, another disease could come along, and the result was often fatal. It was clear that if malaria could be kept under control, mortality could be greatly reduced.

A matter of life or death – the bark of the cinchona tree

By the latter part of the 18th century it was well known that the bark of the cinchona plant was very effective in reducing the debilitating effects of malaria. Cinchona is a tropical shrub or small tree native to South America. The bark of the plant contains quinine and a number of other drugs which are very effective at treating malaria.

Unfortunately the cinchona resisted cultivation for a very long time. This changed in 1860 when cinchona seedlings were brought from South America. Plantations were established in Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka), the Nilgiri Hills (in the present day Tamil Nadu), and other parts of India. By the latter portion of the 19th century, cinchona bark and its derivatives (e.g., quinine) were relatively cheap and easily obtainable. The resulting drop in mortality in the European population made India a considerably less harsh environment.

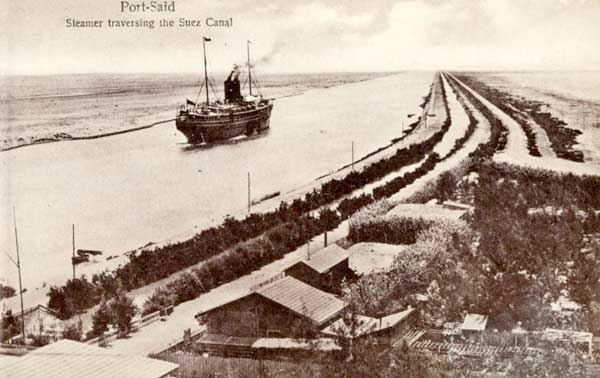

The Suez Canal – The opening of the Suez canal in 1869 had a major impact upon India’s position in the empire. It made it much easier to ship goods between India and Great Britain. By 1882 it is estimated that British commerce accounted for more than 80% of the volume of traffic through the canal.

The Suez Canal greatly improved transportation between India and Great Britain

Improvements In shipping technology – Improvements in shipping also contributed greatly towards increased British presence in India. The early 19th century saw a sharp rise in the availability of the clipper ship. These sailing vessels were manufactured in the United States, Great Britain, and to a lesser extent, in France. They were much faster than previous ships and made transportation much easier. However, shipping technology was improving so fast that by the middle of the 19th century, the clippers were already on the decline. One reason for their decline was the rising popularity of steam ships.

Improvements in shipping technologies reduce travel time between Britain and India

Other Considerations – It is impossible to catalogue all of the innovations which made it easier for Britain to consolidate its control over India. Railroads, telegraphs, improved roads, the list is almost unfathomable. However at this point, I think that you get the picture.

This completes our discussion of the consolidation of India into the British empire. We have shown in some detail how it came about, as well as the economic reasons that made it imperative. This consolidation of India into the British empire made a number of social phenomena possible. One of these was the the anti-Nautch movement.

Part 8 – The Anti-Nautch Movement

We have shown at great lengths the mustering of both the will to execute an anti-nautch movement, as well as the events which gave Britain sufficient resources and control over the subcontinent to actually carry it out. In this next section, we will see how various social forces and imperial machinery fell into place for the execution of the anti-nautch movement. We will get a glimpse as to how it was carried out. We will also examine the dissolution of the tawaif tradition.

Conditions in India Leading to the Anti-Nautch Movement – By the late 19th century, many things had changed in regards to British living in India. Whereas a century earlier, social intercourse between Indians and British expatriates had been extensive, in the Victorian era, this tended to be frowned upon (Nevile 1996). Earlier generations of British freely married Indian women and merged with the local population. But in Victorian India, interactions were carefully proscribed by etiquette. Any Britisher who went beyond the necessary interactions might be accused of “going native”. This was of course a great social sin and caused the offender to be subjected to extreme ostracism. While earlier generations of British knew very well that they were economically and technologically no better than their Indian counterparts, later British were completely convinced that British culture was superior to Indian culture in every regard. This mindset created a widespread disdain for the local culture and traditions.

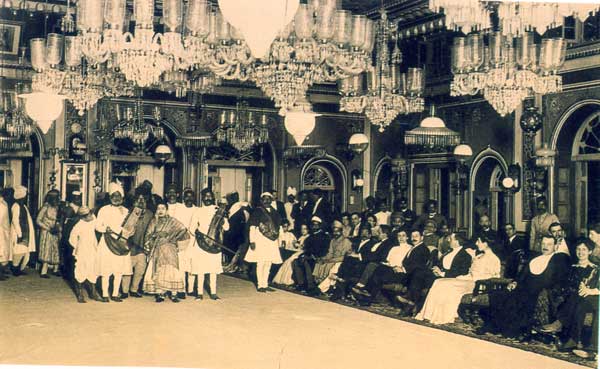

Such disdain for the local culture was easily demonstrated in the deteriorating relations between the British and tawaifs. In the early days of the East India company, it was very normal for British to hire nautch-girls (many of whom were tawaifs) to dance at their social functions (Singh, 2000). However by the later part of the 19th century, social functions tended to be more of the ballroom dancing that one might find in England. Indian dancing started to be frowned upon.

Official function with traditional nautch

The rising unacceptability of Indian dance and its practitioners is illustrated by an incident that occurred in 1890. Prince Albert visited India and was entertained to a traditional Indian dance. Visiting dignitaries had been entertained to traditional Indian dance for as long as anyone was aware; however this time things were little different. There were protests from many quarters, especially from a Christian missionary by the name of Reverend J. Murdoch (Nevile 1996). He printed a number of publications strongly condemning these “nautch parties” and called for all British to refrain from attending them.

The persecutions of Indian dancers by Reverend Murdoch was just a small indication of a social phenomenon that was emerging. This was the spread of the Social Purity movement from Great Britain to India. As it turned out, once the Social Purity Movement spread to India, it would assume a character that in some ways was different from its original British form.

The large number of missionary based publishing houses was one reason for the rise of the anti-nautch movement. The Christian missionaries controlled a very significant portion of the publishing houses in the subcontinent. Initially this publishing infrastructure was devoted to the publication of bibles in the various indigenous languages. However as the capacity of these publishing houses increased, they very quickly branched off into other directions as motivated by issues of the day. By the latter part of the 19th century, Indian dance was considered to be one such issue. One of the early agitators against Indian dance was the “Madras Christian Literature Society”; they printed a fair amount of anti-nautch literature.

The views of many of these Christian missionaries were at times extreme. Many Christian publications went so far as to say that simply looking at an Indian dance was sufficient to arouse un-Christian feelings. But it was not just British and Indian Christian converts that were behind the Anti-Nautch moment, the Indian bourgeoisie was also involved.

Anti-Nautch Movement in Full Force – It is difficult to ascribe the birth of a movement to a particular date, but for the purpose of this article we will consider 1892 to be the birth of the anti-nautch movement. This was the year that an an appeal was put forth by the “Hindu Social Reforms Associations” simultaneously to the Governor General of India and the Governor of Madras. The official replies from both the Viceroy and the Governor of Madras were polite, but clearly denied any connection between devdasis, dance girls, and prostitution.

However, religious zealots have never been ones to allow facts to interfere with their thinking. They were resolute in their efforts. Since they were unable to get any official action on this matter, they started to directly target individuals who hired dancers to entertain at their social functions. They called for the British to boycott dance girls and functions where “nautch-walis” were hired.

The anti-nautch movement very quickly spread from the devdasis of the South, to the tawaifs in the North (Neuman 1980). As social purity organisations were established in Northern India, the tawaif became the target there. In the next few decades, organisations such as the “Punjab Purity Association” (Lahore), the “Social Service League” (Bombay), and a host of others were established. One publication from the “Punjab Purity Association” quotes the social reformer Keshub Chandra Sen as saying that the nautch-girl was a “hideous woman…hell in her eyes. In her breast is a vast ocean of poison. Round her comely waist dwell the furies of hell. Her hands are brandishing unseen daggers ever ready to strike unwary or wilful victims that fall in her way. Her blandishments are India’s ruin. Alas! her smile is India’s death.”

Salvation Army in India

Another example of the extreme zeal of many who pursued the anti-nautch moment may be seen in the case of miss Helen Tennant. She truly believed that it was her assignment from God to abolish dance girls. She came all the way from England to India for this purpose.

The efforts of the anti-nautch activists continued unabated for years. It spread out of the circles of missionaries and social purity reformers, and into the mainstream. It finally reached a point where in 1905, contrary to tradition, it was decided not to have an Indian dance at the reception for the Prince of Wales in Madras.

At this time, the situation of the tawaif was very bad. The social expectations created by the anti-nautch movement had become a self fulfilling prophesy. Decades of persecution and a boycott of their arts, created an environment of desperation for the tawaifs. They were unable to pursue their arts due to social pressures; therefore there became little incentive to maintain artistic standards. In such desperate circumstances, the tawaifs had no recourse for survival other than the common prostitution for which they had been accused.

In this environment, there were serious concerns whether their art-forms would survive. The kathak dance, the thumree, the gazal, and dadra, were all under serious pressure. But as we will see, there was a curious and complex chain of events which transpired which rescued the art-forms, even though the tawaif tradition itself was beyond being saved.

The nature of dance and dancers was also evolving under pressure from the anti-nautch movement. The custom of using young boys to dress as women and perform the female roles rose in popularity. (Rosenthal, 1928)

Part 9 – Passing of the Torch

The arts of the tawaifs did not die with them, but were instead passed on to a new generations of performers who were unconnected with the tawaif tradition. This metaphoric “passing of the torch” was part of a complex series of events. This section will deal with social and historical processes behind this transfer of these arts. We will also look at a small sampling of people who were involved in this process.

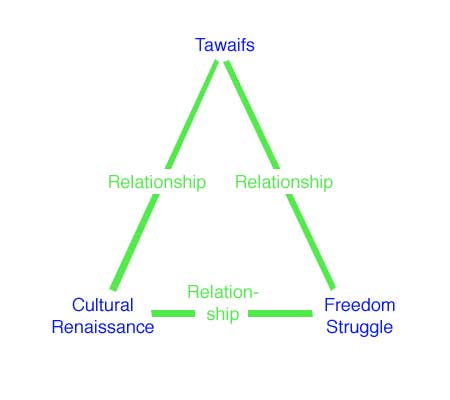

New Social Dynamics – At the height of the anti-nautch moment, a curious chain of events transpired in India. The tawaif, the freedom movement, and an emerging cultural renaissance in India, were all thrown in together with interesting results. In a nutshell, we can say that many people worked to forge a new India, saved the arts of the tawaif, but at the same time destroyed the tawaif tradition.

From the standpoint of the tawaifs, the social dynamics were changing fast. This was a transitional period in Indian history, and at times things were quite complicated. However for the purpose of this modest article, we will look at these things according to a simple model.

Model for our discussions

In this model there are six things that we need to familiarise ourselves with. They are:

- The Tawaifs

- The Cultural Renaissance

- The Freedom Struggle

- The Relationship Between the Freedom Struggle and the Cultural Renaissance

- The Relationship Between the Tawaifs and the Freedom Struggle

- The Relationship Between the Tawaifs and the Cultural Renaissance

It is interesting to note how the British have fallen out of this picture. They were still a force to be reckoned with in the early 20th century, but as far as the tawaifs were concerned, they were becoming irrelevant.

Tawaifs – Let us review the state of the tawaifs at the turn of the 20th century. The tradition had been under pressure for more than half a century. The dissolution of many of the princely states that had been their patronage, placed them in a precarious economic situation (Singh, 2000). Two decades of persecution by British, as well as local social purity organisations, reduced both their economic status as well as their social standing. The difficulty in getting bright young girls who could handle the years of rigorous training was reducing the quality of the tawaifs. The boycott of their performances made the tawaifs disinclined to put in the efforts to maintain artistic standards. All of these events conspired to push the tawaifs into the very prostitution that the social purity activists had long accused them. But the biggest problem was a lack of social relevance. It was clear that that the tawaifs were a dying breed.

Cultural Renaissance – The early part of the 20th century saw India in the midst of a cultural renaissance. Decades of English medium, convent education, had a interesting impact upon Indian society. It had the desired results (at least from the British standpoint), of producing an army of capable “babus” who dutifully carried out the administration of India for the benefit of their British masters. Unfortunately, it created a peculiar, almost slave mentality among this class. There were deep rooted feelings of inadequacy bordering on self-loathing. Just as in the physical world where every action has its reaction, so too we find similar reactions manifest in the social arena. In many quarters, the middle class begins to deeply reject the mindset of self-loathing and inadequacy and begins to take pride in their Indian self-identity.

But the obvious question was “What is this self-identity?” This thirst for a sense of Indian self-identity fuelled a very powerful cultural renaissance. Across the subcontinent, people started to take note of virtually every piece of folk art, classical art, music, dance that they could find. People were actively engaged in discovering, and at times even fabricating a self-identity.

Freedom Movement – It is ironic that it was the British that created the basic framework for both the Indian freedom movement as well as a united and free India. From Kanya Kumari to the Himalayas, the British had established English medium schools where Indians became familiar with European concepts (including the European concept of nationalism). This bourgeoisie, had the ability to move from North to South and East to West and meet with other Indians who had compatible world views. The British had unwittingly united a subcontinent that had been divided for ages by political, linguistic, and cultural differences. In this environment, the formation of a independence movement was inevitable.

Such pan-ethnicism of the Indian bourgeoisie may have been very convenient in the early days of the freedom struggle, but it was neither sufficient, nor an appropriate a vehicle to build a sense of national identity. It was clear there had to be an Indian sense of self-identity if the struggle for freedom were to be successful.

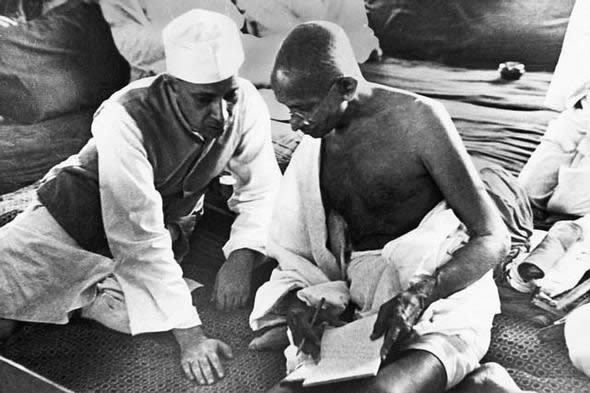

The freedom movement was by no means homogenous, for there were many approaches and ideas. Some espoused largely non-violent, economic means (e.g., Gandhi, Nehru). Some advocated a military approach (e.g., Chandra Bose). Some advocated for grass roots guerrilla activities (e.g., Bhagat Singh). Regardless of which approach a freedom fighter was adhering to, they could not forget past failings.

Relationship Between the Freedom Struggle and the Cultural Renaissance – The failure of the Uprising of 1857 was not lost to this new generation of freedom fighters. It was recognised that one of the reasons that the Uprising failed, was that after initial military successes, there was a sense of “now what”. The concept of a unified “Azad-e-Hind” (Independent India), was missing. The Uprising of 1857 was comprised of disparate Indian elements who had legitimate grievances, but no clear plan as to what to do after the British were defeated. This lack of a clear goal allowed the Crown to mobilise her military strength and suppress the insurrection. The Indian intelligentsia were determined that this would not happen again.

British retaliation against Uprising

The intelligentsia of the freedom movement were very aware of the problem. They realised that the only way to avoid the fragmentation and lack of direction, was to create and maintain a unified sense of self-identity. This was in no way a simple task; historically the South Asian sense of self-identity was determined by communal identifications.

Many different approaches were used. Not all of which had the same level of effectiveness. Some actually turned out to be counter productive.

Many invoked invoke the mythical concept of Bharat Varsha (भारतवर्ष), as a tool to help the common man grasp the concept of nationalism. The image of Bharat Varsha as promulgated by many freedom fighters, was that of a period when all of South Asia (according some, the entire world) was governed by Hindu dharma. This may have been a convenient introduction to the concept of nationalism for many commoners, but unfortunately it would have uncomfortable repercussion by alienating large portions of the Muslim populations of South Asia.

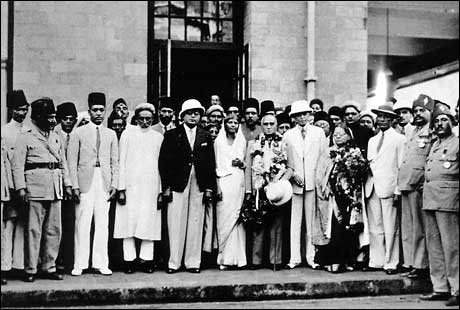

The All India Muslim League was established in 1906, but gained popularity in the 1930s; it began to push a very different agenda. Their supporters tended to push Islam, along with the Urdu Language, as their means of establishing a sense of self-identity.

All India Muslim League 1936

The Indian National Congress was attempting to avoid a partition of India. It was clear that the Hindu oriented Bharat Varsha approach would only further alienate the Muslim minorities. However concentrating on traditional arts seemed a very safe way to create a national identity without causing any problems. Therefore, the support of the arts became a component of the freedom struggle. Even after independence it was still pursued. Although the objective of attaining independence was achieved, there was still the issue of national integration.

Indian National Congress hunts for a way to create a national identity

Of course this is all history now. The All India Muslim League and the Indian National Congress continued pursuing very different agendas, and using very different approaches; and India and Pakistan were separated in 1947.

Relationship Between the Tawaifs and the Freedom Struggle – The tawaifs and their place within the freedom struggle was problematic from the very beginning. On one hand, the British made it very clear that they would never support the tawaifs; therefore any significant support for the British Raj by the tawaifs was not really a consideration. But it was also clear that there was not going to be much support from the freedom movement as well. Founding members of both the Indian National congress as well as the All India Muslim league were products of an English Victorian school system. Therefore, they had a strong tendency to reject the tawaifs outright as mere prostitutes.

That is not to say that there were not interactions between freedom fighters and the tawaifs; but this did not represent an endorsement of the tawaifs. Individual tawaifs were known on occasion to support the Indian National Congress with financial contributions; but there was really no reciprocation of support by the independence movement. It was clear that as a matter of policy, the Indian National Congress considered the tawaifs to be a social evil; one, like sati (self immolation of widows upon husband’s funeral pyre), child marriages, and restrictions on widow remarriage, needed to be eliminated.

Relationship Between the Tawaifs and the Cultural Renaissance – The role of the tawaif in the cultural renaissance was extremely complicated and at times troublesome. Many in the middle class admired and respected the arts of the tawaifs, but they could not relate to the culture of the tawaif. The tawaifs still tried to maintain 18th century world views, while the middle class were firmly embracing the 20th century.

Simply put, the arts of the tawaifs were taken from them and given to the middle class. This process has at times assumed very different value judgements. Those sympathetic to the tawaifs, tend to view their arts as being stolen from them. Others who are more sympathetic with the middle class nature of the renaissance, look upon it as a form of democratisation of the art-forms. They point out that in the old feudal system, the only people who could enjoy theses arts were the extremely wealthy ruling classes. They look at the passing of the arts from the tawaif to the populace as a cultural “redistribution of wealth”. If I may interject my own feelings, I look upon it as a “rescue” of the arts. It was clear that the tawaifs were disappearing and it was necessary to find a new home for their arts, otherwise they may have disappeared.

Part 10 – The Rescuers

The passing of the tawaif’s arts to the middle class was not an easy job. It could not have been done without the sacrifice, and hard work, of many people. This included tawaifs as well as members of the middle class. This process required the middle class to submerge themselves into the kotha culture of musicians, poets, and tawaifs; take their arts; and then use modern approaches to preserve and propagate them. Such endeavours involved combinations of modern musicology, gramophone recordings, publication of books, and a wide range of activities. Although we consider such activities normal today, they were unknown to many of the tawaifs, and considered to be revolutionary at the time.

A Few Famous Tawaifs of the Time – Many people need to be thanked for the rescue of these arts. These were tawaifs who broke with tradition in very important ways. We must remember that the professional culture of the kothas was characterised by extreme professional secrecy. Tabla players frequently used to refuse to perform certain material in the presence of other tabla players. I am told that there was a sarangi player who used to play with his fingers behind a veil so that no one could see his technique. Tawaifs used to perform their arts only before extremely select viewers. When we remember this almost paranoid obsession with professional secrets, it is very remarkable that these tawaifs were willing to perform before large public audiences. The fact that they would be willing to have their songs recorded on disk was itself remarkable. The fact that they would accept as dance students people who were not specifically chosen to carry on the tradition in the kothas was amazing. All of these things point to a degree of forward-thinking that was rare in that culture. For such forward-thinking, we owe them an amazing debt of gratitude.

Let us look at a few of these remarkable tawaifs:

Jaddanbai (1892-1949) – Jaddanbai was a tawaif who by all accounts was an extremely remarkable woman. She is mostly remembered as the mother of the Bollywood film star Nargis, and grandmother to Sanjay Dutt. However in her time, she was a master music composer, singer, actress, and even film maker. It is interesting to note that there is a persistent rumour that Jaddanbai was the illegitimate daughter of Motilal Nehru by way of her mother, the famous tawaif Daleepabai of Allahabad.

Jaddanbai (extreme right) with Dilip Kumar, Nargis, and Mehboob.

Gauhar Jan (1873-1930) – Gauhar Jan was a tawaif whose birth name was Angelina Yeoward, when her mother converted to Islam, Angelina took the name Gauhar. She was very gifted in both singing and kathak dance; she was only 15 when she gave her first performance. She was very famous in Calcutta in the early part of the 20th century. Her fame was as much for her lavish lifestyle as it was for her art (Misra, 1990). We are fortunate that she has left us with numerous recordings made during her lifetime.

Gauhar Jan with Gramophone.

Begum Akhtar (1914 – 1974) – Finally we must also not forget the late Begum Akhtar. She may be considered one of the last of the tawaifs. She gave her first public performance at the age of 15; we are fortunate that she lived recently enough that a large number of her gazals, dadras and thumris could be preserved in recordings. She was considered to be a cultural icon who represented India as part of cultural delegations (Misra, 1992). Her influence over the musical world cannot be overstated.

Begum Akhtar.

A Few Famous Non-Tawaifs of the Time – Our gratitude must also be extended to non-tawaifs as well. As the tawaif tradition was declining, there had to be non-tawaifs ready to receive the arts and carry them on. The hardships endured by the non-tawaifs in this process was no less than their tawaif sisters. Although they were products of a different cultures and different times, they still had to endure considerable amount of ostracism.

But the difficulties of the non-tawaifs extended beyond mere social pressures. The process of propagating theses arts in a new environment required an extraordinary degree of innovation. We must not underestimate the enormity of the task of translating an art-form from one time to another, from one place to another, and from one culture to another. Never forget that a 19th century kotha was a very different place from a 20th century auditorium. The music business in the 20th century required considerably more flexibility than the system of royal patronage of the 19th century. In all, the job of being recipients of this art-form was a very challenging task.

Men played an especially important role in the perpetuation of these art-forms. During the height of the anti-nautch persecutions, only men could perform without fear of being accused of being prostitutes. Therefore, one should not be surprised to find a fair number of men among the people we must thank.

Sukhdev Maharaj & Sitara Devi – Two very important non-tawaifs were Sukhdev Maharaj (1888-?) and his daughter Sitara Devi (circa 1920 -2014). Although the name Sukhdev Maharaj is virtually unknown, Sitara Devi is remembered as a very famous kathak dancer.

Sukhdev Maharaj was a Brahmin from Varanasi (Benares) who was a well known Sanskrit scholar of the Vaishnava tradition. He was inspired to take up Kathak by Maharaj Bindadin (Misra, 1992). Sukhdev Maharaj became a very accomplished kathak dancer, and earned his living performing and teaching. He taught the art of kathak to both his sons as well as his daughters. He even had a school in Benares where he taught many people. For this, he suffered a tremendous degree of ostracism, but he persevered.

It was Sukhdev Maharaj’s daughter Sitara Devi (born early 1920’s), who really became famous. Her birth name was Dhanalaksmi, but she was nicknamed “Dhano”. She initially had informal training under her father, but when it became clear that she had talent, her training was then entrusted to her older sister, Tara (Tara was the mother of the famous dancer Gopi Krishna). It was about that time that she assumed her stage name “Sitara Devi” (lit. “Star Goddess”). When she was still a young girl, her family moved to Bombay. There she continued to perfect her art. Very early on, she was dancing in the films. However, she gave this up, feeling that the film world was ill suited to her traditionalist tastes in dance. She continued to dance for many decades and won a great many honours.

Sitara Devi

Vishnu Digambar Paluskar (1872-1931) – One other person that we are indebted to is Vishnu Digambar Paluskar. He established the first modern school of music: this was the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya which was established in Lahore in 1901 (Deodhar, 1993). This school was open to all, and was structured along the lines of the numerous English medium schools which had been set up in India in the later half of the 19th century. This model is still used for the various government and private schools, spread across India today.

Vishnu Digambar Paluskar

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860-1936) – It is interesting that one of the non-tawaifs that we are indebted to was actually a lawyer; this was Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande. We are indebted to him for documenting a vast corpus of rags and compositions, and codifying the north Indian system of music. Furthermore, it is his system of notation which is the most widely accepted in Northern India. At the turn of the 20th century, he published his four volume magnum opus entitled Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati. Even today, it is considered to be the standard reference work on the subject.

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande

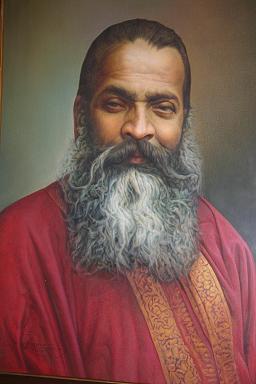

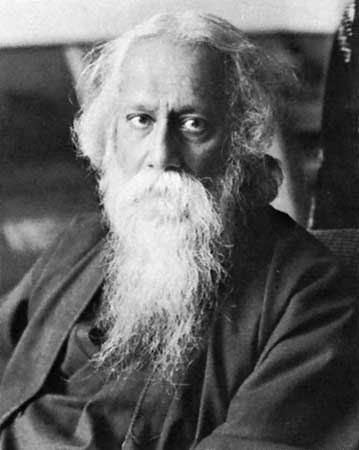

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) – Perhaps the name which is most associated with the cultural renaissance was Rabindranath Tagore. He was active in a number of endeavours including music, poetry, literature, and religion. He became the first Indian to win the Nobel prize when in 1913, he won the Nobel Prize for literature. He composed a vast number of songs, based upon traditional and classical music; today these are known as Rabindra Sangeet. His contributions to the development of the artistic scene of the late 19th and early 20th century cannot be overstated. It was almost as if he personally epitomised the cultural renaissance of India.

One project which is closely associaed with Tagore is Shantiniketan (Rosenthal, 1928). During the freedom movement, it was a school where students from all over India could come and be instructed in an Indo-centric environment. Shantiniketan was started by Rabindranath Tagore’s father, Debindranath Tagore, but greatly expanded by Rabindranath. Among the subjects taught were music and dance forms which previously were the specialties of the tawaifs.

Rabindranath Tagore

It is pointless to give any more than these few samples of musicians, dancers, and scholars who were responsible for saving these art-forms during an extremely trying period of Indian history. We can only mention great artists such as Gopi Krishan, Uday Shankar, Rukmini Devi Arundale, Ram Gopal, and a host of others. We hope that these few examples will, at least illustrate the hardships that both the tawaifs as well as the non-tawaifs had to endure, so that we can enjoy classical music and dance today.

Part 11 – Effects of the Anti-Nautch Movement on North Indian Music

This section will examine the various musical genres, dance forms, as well as the instrumental accompanists that were associated with the tawaif. We will see how they suffered. We will also look at how the music changed as it was taken out of the 18th century tawaif culture and passed onto the 20th century middle class culture. We will see how the process of changing the culture in which these arts existed had profound affects upon them. In particular, we examine the decline in the Muslim tawaifs and their accompanists with the subsequent transfer of their arts to a largely Hindu middle class.

Cultural Recontextualisation – Music and dance are inextricably linked to the cultures in which they are placed. When a musical form is transferred from one cultural context to another, this is an example of cultural recontextualisation. To a certain degree this is a normal process. Times change and the cultural environment changes with the time, therefore musical styles are constantly undergoing some slight degree of recontextualisation, otherwise they pass out of fashion. But occasionally there are major examples of cultural recontextualisation. These are rare, but when they do occur, there are profound changes in both the performance as well as the consumption of music.

One example of a major recontextualisation of music may be seen in jazz. In the space of less than a hundred years it changed from being a southern Afro-American art-form, into an international, urbane art-form; one in which the majority of its practitioners are white. In the process of being recontextualised, the music underwent drastic changes. It is useful to keep this jazz analogy in mind as we look at the recontextualisation of the tawaif’s arts.

The change in cultural context of the tawaifs art-forms may be examined very simply. We look at the culture from which the arts came, and we look at the culture into which the arts have come to occupy today.

Let us first review the culture in which these arts developed. With the exception of the area around Benares, Jaipur, and a few other small principalities, the tawaifs were largely Muslim. Their accompanying musicians too, were largely Muslim, and came from various classes of hereditary musicians. Although the tawaifs were generally known for their extremely high level of formal education, their circle of accompanists were often illiterate and occupied a lower strata of society. They subsisted on royal patronage, so they were ever mindful of the political situations in their kingdom; but they were not above being active participants in these political machinations.

But the cultural environment in which these arts came to reside was very different. Kathak dancers, classical vocalists, and their accompanying musicians have largely become Hindu. Today their socio-economic strata is very different; today it is largely a middle, to upper class affair. The days of the illiterate musician are over; today’s artists typically have a respectable level of formal education. Involvement in the political arena is no longer necessary, so most musicians and dancers today tend to have no more interest in politics than the public at large.

We will see later, that these differences have come to be reflected in very profound ways. In particular, there are fundamental differences between Hindu and Islamic world-views. These differences, when couple with a seismic shift in the culture of India during the late 19th and 20th century, meant that these musical forms do not have the same significance. Neither are they performed in the same way.

Part 12 – The Tawaif’s Arts

There were a number of arts that had a strong association with the tawaifs. Let us examine these and see how they have fared.

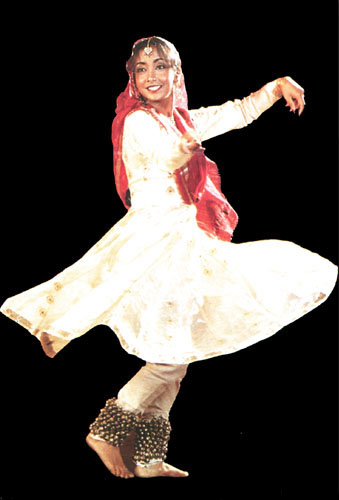

Dance – Dance was the focal point of the anti-nautch movement. Very obviously the dancers themselves suffered the most, and the dance itself was under considerable pressure. It is interesting to note that the extreme pressure placed upon kathak and its exponents caused this dance to bifurcate into two genres. There is the kathak and there is the mujara (मुजरा)

A comparison between the kathak and the mujara is in order. kathak is a very refined and formalised dance form. It is a combination of narrative elements as well as highly abstract “pure” dance forms. There is a great reliance on complex rhythmic forms. In contrast, the mujara is considered to be a South Asian erotic dance. It is considerably less formalised, and may be a hodgepodge of cabaret, belly-dance, and kathak. Today it is often indistinguishable from the typical Bollywood dance.

Kathak dancer

Typical Bollywood Mujara

It is interesting to note that the differences between the contemporary mujara and kathak are very great. They are so great that even an uninitiated audience can readily discern the difference when the two are performed side by side. Yet in spite of the clear stylistic differences, the average uninitiated audience tends to confuse mujara and kathak. The reason for this confusion is actually quite simple and may be summed up in a single word – Bollywood.

Bollywood has invoked “kathak” dances for many decades. But what it has been passing off on the public has generally not been the refined kathak, but the mujara variety. Therefore, it should be no surprise that the average public is confused on this matter.

Historically, the mujara and the kathak were one and the same; the bifurcation is a late 19th/ early 20th century phenomenon. It is useful for us to step back and look at the cultural circumstances that lead to this bifurcation.

Kathak in the 18th and early 19th century was a very highly refined and formalised art. The patrons of the tawaifs were very refined too, and no strangers to the arcane conventions of the art. As matter of fact, one of the greatest patrons of the tawaifs was the ruler of Avadh (Oudh), the Wajid Ali Shah, who himself was so versed in the arts, that he is credited with numerous kathak pieces. In this rarefied environment, it is no surprise that kathak was able to attain incredible levels of sophistication.

Unfortunately this rarefied and sophisticated environment did not survive. In the mid to later part of the 19th century, large numbers of independent principalities were annexed into the British Empire. With the decimation of the independent principalities, the tawaifs were forced to seek their patronage with the nouveau riche, who typically did not understand the subtle conventions of the art-form. In order for the tawaifs to survive, they were forced to concentrate on ever more vulgar aspects of their repertoire, thus initiating a downward spiral in artistic content. The situation for the tawaifs became even worse in the early decades of the 20th century, when they had to endure a considerable amount of professional competition from the non-tawaifs who were entering the dance field. These non-tawaifs appropriated the more dignified repertoire, and left the tawaifs with no recourse other than to continually emphasise the erotic material.

The rise of the film industry further complicated the situation. The mujara dance was the original “item number“, but these films started to mix various folk and Western elements into the dance. This began to be reflected in the repertoire of the tawaifs. The mujara continued its downward spiral. It declined to the extent that through much of the first half of the 20th century, the mujara was only to be found in the “red light” districts of Indian cities. Today one can still find mujara dancers, but their connection with the noble kathak of the past is essentially severed.

But the evolution of the refined Kathak proceeded down a completely different line. In the later part of the 19th century, men were becoming the repositories of the kathak repertoire. Only the men could perform without fear of being branded as prostitutes. During the cultural renaissance, the narrative aspects of the dance started to be re-emphasised. This was especially true of stories related to Krishna and other traditional Hindu themes. This was a reflection both of the changing makeup of the artists, as well as the changing makeup of the audiences.

By the second quarter of the 20th century more non-tawaif women were entering the profession. But in order to maintain their “izzat” (dignity) they tended to steer away from erotic elements that had once been a component in the repertoire. For a long time the more classical kathak was nearly devoid of erotic content.

So we can simplify the picture by saying this. The kathak repertoire of the old tawaifs became bifurcated in the process of the recontextualisation of the art. As the tawaifs descended into prostitution, their emphasis on the erotic aspects of their arts intensified. This became the mujara. Conversely the new the middle class artists developed the non-erotic elements which have come to be viewed as the present kathak.

It has not been my goal to conjecture as to the future of the kathak, but in this case think I should. We are now witnessing a reintroduction of erotic content into the repertoire of the kathak dancer. This really has nothing to do with the old tawaifs, but is instead a reflection of several phenomena. On one hand, we have the Bollywood film industry with its extremely powerful grip upon popular culture. Bollywood has continually pushed the more erotic mujara as being kathak. Furthermore, we have a society today which is much more tolerant of erotic content in art. This coupled with the fact that many concert goers are blithely unaware that there is even a difference between kathak and mujara. And we must not forget that audience expectations is an extremely powerful influence on the development of any art.

The result of these various influences is interesting. We are seeing more fusion of the mujara and kathak. In the next few decades it is possibly that they may converge. This is an interesting thing to watch. If it does happen, it will be based upon very different set of social and cultural pressures than that which we have been examining in this article.

Vocal forms – If we look a the the influence of the anti-nautch movement and the recontextualisation of the vocal forms, we get a slightly different picture. By the time that the anti-nautch movement began, most of the vocal forms were shared by tawaifs and non-tawaifs alike. This was a major contrast to the kathak / mujara dance forms that the tawaifs had a near monopoly on.

Since the vocal forms were shared by both tawaif and non-tawaif, the impact of the anti-nautch movement was not nearly so profound. The only clear impact that the anti-nautch movement had was that, for a period, people tended to boycott the female artist in favour of the male vocalist.

But that is not to say that there were not changes. There was still the changes which occurred as the music was taken up by the Hindu middle classes and taken from the largely Muslim hereditary musicians. However since these changes were due to events that were only loosely connected to the anti-nautch movement, we will not discuss it further here.

Part 13 – The Tawaif’s Accompanists

A movement on the order of the anti-nautch movement would be expected to cause a considerable amount of collateral damage. Remember that the nautch was not merely an Indian dancing girl, but represented a large and more complex social, artistic, and economic entity. If the tawaif suffered socially and economically, then her musical accompanists also suffered, the tailors that specialised in their refined expensive, yet very specialised clothing also suffered. Furthermore, it is not just people who suffer, but entire musical and dance genres suffer. Let us look at how some of these other entities were affected. (4)

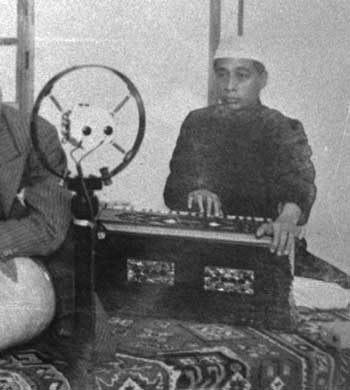

Sarangi vs. Harmonium – The rise of the harmonium and the decline in the sarangi (सारंगी) are directly attributable to the anti-nautch movement. The sarangi was closely identified with tawaif, In the past, it appears that on occasion Indian dancing girls would be accompanied by two sarangis (Rosenthal, 1928).

But the decline of the institution of the tawaif and its growing stigma adversely affected the sarangi players. that sarangi players found it extremely difficult to find work (Neuman 1980). The stigma attached to the sarangi was so great and lasted so long, that it was only around the turn of the 21st century, that we have seen any major resurgence in interest in this instrument.

sarangi player

The stigmatisation of the sarangi and the sarangi players had a very obvious problem. If a vocalist was wanting to “clean up their image” by avoiding the sarangi, then what was there to fill the void? This is where the harmonium enters the picture. When singers, usually male singers, wished to distance themselves from the tawaif, the harmonium provided a convenient way to do it. Since it was a European import, a male singer could present himself with a very different image than if he had chosen a sarangi. This image made it much easier to get performances among the rising Indian bourgeoisie.

Harmonium player in old radio broadcast

It should be noted that many ascribe musical reasons for the rise of the harmonium. It is true that the fixed tuning of the harmonium makes it very convenient to maintain the same key throughout a performance. But that is hardly an advantage when its tempered scale is fundamentally out of tune with Indian scales. Furthermore, its inability to handle certain slides makes many rags almost impossible to perform. I think that even a cursory look at the musical history of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, makes it clear that it was social, and not musical pressures, that cased the sarangi to be replaced by the harmonium.

Tabla – Tabla (तबला) is another instrument that, like the sarangi, became linked to the tawaif. (Neuman 1980) The result was that during the height of the anti-nautch movement and even for a long time afterwards, there was a tremendous stigma attached to both the tabla as well as tabla players. The term “tabalchi” (तबलची)(i.e., one who plays the tabla), became synonymous with a drunk, a pimp, or a vulgar member of society.

Tabla player