A.K.A. Dotar or Dotara

By Mir Ali Akhtar

and

David Courtney ![]()

The dotora (a.k.a. dotar, or dotara) is an instrument much associated with the musical culture of the Bengali people. This instrument is found throughout West Bengal, Bangladesh, and even Assam, and Eastern Bihar. This instrument is greatly favoured by the wandering minstrels known as the Baul. This instrument may be thought of as a Bengali version of the rabab. Although the name is the same, this instrument should not be confused with the simple two stringed dotar found through out South Asia.

The origin of the terms “dotar” or “dotora” are interesting. The word is found in Bengali (i.e., Bangla Bhasha), which is a member of the Eastern Group of Indo-Aryan languages (Grierson,1903). The etymology is based upon three components, Do-Tar-A. In Bengali “do” means “two”; “tar” means “string”; and the “a” appended to the end means “of”. Therefore, the word dotara, means “of two strings”. Naturally there are regional variations to pronunciation. Especially note that the term “tar” as one would find in Hindi and Urdu, acquires the more open Bengali pronunciation of “tor”. Other regional variations are also easily found. For instance, in the Rangpuri dialect it is pronounced “dotra” but it is also pronounced “dotora” in Rangpuri’s more poetical forms, (e.g., vaoaiya lyrics.) It is interesting to note that, although the term “dotora” implies two strings, most instruments have a minimum of four strings, and even six is not unusual.

As with any folk instrument, regional variations in construction abound; however, there are two main styles. In Bangladesh, one of these is found in the north and the other is found in the south. These show several differences in both construction, tone, and usage.

The figure below shows a typical example of the southern version of the dotora. This version is commonly used in a wide variety of Bengali music. Notice the carving at the upper end of the necks, these are usually designs of animals, peacocks or other birds. It is interesting to note that this version is also known as swaraj and surasanggraha, or rahr Bangla.

Dotora typical of the type found in Southern Bangladesh

The southern Bangladeshi style of dotora is in many ways reminiscent of the sarod. It tends to use metal strings. Very often it also uses a metal finger board. These give it a very bright sound. This style is especially popular among the bauls and the fakirs. This is the style dotora which is most often comes to mind whenever the dotora is referred to.

There is another style of dotora which is not so well known. In Bangladesh, this version of the dotora tends to be found in the tribal areas in the north; but this style is also found in West Bengal, Assam, and Eastern Bihar. This version is shown in the figure below:

Dotora typical of Northern Bangladesh

We see that there are numerous differences between this style and the more widely known southern version. One should note that this version is less adorned. Also, this style of dotora tends to use strings made of gut or cotton fibre. Furthermore, this version has a wooded fingerboard instead of the metal plate often found in the Southern version. This dotora is much closer to a rabab in both sound and construction. Its sound is generally considered to be more appropriate for the vaoaiya, bhaaiwaiya, jaalpariya, and mahishali styles of music. This type of dotora is also sometimes referred to as a bhhawaiya dotar.

Construction and Parts of the Dotora

It is appropriate for us to look at the construction of the dotora in greater detail. The overall form of the dotora is of a resonator and a neck, a number of pegs and strings, (usually four), and a skin to cover the resonator. These will be described in greater detail.

Parts of the Dotora (top view)

Parts of the Dotora (side view)

Parts of the Dotora (playing surface)

Body and Resonator

The body of the dotora is probably the most important part of the instrument. It is upon this body that all of the pegs, strings, and membrane will be attached.

One item to pay particular attention to is the carving (or lack there-of) at the upper-most portion of the instrument. This decoration is usually of a bird or animal motif, and it is a ubiquitous part of the southern style of dotora (swaraj). This is generally called “mogra”. Unlike the southern form, the northern version does not have any top decoration. One should note that these days, one is starting to see these animal decorations (mogara) even on some northern Bangladeshi dotoras.

Let us look at the fashioning of the body of the dotora. It is important to remember that although it is fashioned from a single piece of wood, this main body is of at least three sections, and possibly a fourth. These sections are the bati (i.e., the bowl of the resonator), dhor (i.e., the neck), and the muga (i.e., hollow portion for fixing tuning knobs). The optional fourth piece is the decorative piece at the end (mogra) Let us now look at the fabrication of the body in greater detail.

The first and foremost job in making the body is to start with a suitable piece of wood. This wood is usually of jackfruit, neem, or local chaiton. It should also be of suitable dimensions. This should be two feet long, six inches high, and 6 inches wide. It should be even longer if one is going to allow room for the decorative piece (mogra). The shape is carved and gouged using standard carpentry tools.

Here are the measurements for the various parts of the body:

Bati – The bati is the bowl, or hollowed out section, which forms the main portion of the resonator. Its diameter should be roughly five inches, and the height at the centre should be about 4.5 inches. There is a fair amount of latitude concerning the shape. It does not have to be round, a certain elliptical quality is quite acceptable. But, one should not neglect to leave a protrusion at the base of this resonator; this will be used to attach the strings.

Dhor – This is the neck. Its length is 17 – 18 inches. The width at the base of the resonator (i.e., the bati) is around 2.5 inches. Height of the neck (i.e., the dhor) and the length is up to the artist’s individual preference. Every musician has a particular “feel” that they like.

Muga – This is the peg box. It is the hollow section where the tuning pegs connect. The overall length should be about four inches; the width should be about two inches and it should be whatever depth that will allow a comfortable placement for the tuning pegs. One should leave several inches from the top end of peg box (opposite side of resonator end) to put whatever decorative headpiece one may desire. The muga (peg box) must then be hollowed out to forma rectangular opening. This opening is known as the “mugastan” (literally “the place of muga“).

Mogra – If one is making a southern style of dotora, then allowance must be made for the decorative piece at the end (mogra). This is basically an artistic call. One may allow for anywhere from one or two inches up to eight inches depending upon how fancy one wishes to be. Themes of birds and animals is the norm, but by no means is it obligatory.

The carving of the wood for the main body is now finished. However, the body is not finished until the membrane is attached.

Chauni – The chauni is the membrane that covers the bati. The attachment of this skin is performed as follows:

The skin of a large lizard, or the rawhide of a young goat is first soaked in water until it is very soft. It is said that Iguana skin gives the best sound. It is then bound to the lip of the resonator and glued in place. After the glue has set and the membrane dried, any excess is cut away. This membrane on the dotora is known as “chauni”.

Sound holes are now burned into the skin. If one attempts to cut these holes instead of burning, there is a tendency for them to tear. These sound holes are known as “chad”.

At this point, the body may be painted according to ones preference.

Face Plate – If one is making a southern style of dotora, then there is a good likelihood that you will be wanting to put a metal faceplate on. This faceplate is often used because the southern style of dotora uses metal strings, and the constant fingering of metallic strings against a wooden fingerboard tends to ruin the fingerboard. The highest quality dotoras tend to use a nickel or chrome plated brass. Ordinary sheet metal may be used for lower quality instruments.

A surprising addition to the instrument makers craft is the use of laminates (i.e.,. Decolam, Formica, Arborite, Alpikord, etc). In the last few years this has emerged as a workable and economical alternative to the metal fingerboard. This tends to be found only on extremely inexpensive southern styled dotoras.

The method of attaching the faceplate depends upon what material is being used. Metallic faceplates tend to be attached with screws. This allows the plates to be removed to facilitate the reskinning of the dotora which must be performed periodically. The inexpensive “decolam” versions have the plate fixed with contact adhesive.

The main body is now finished.

Tuning Pegs

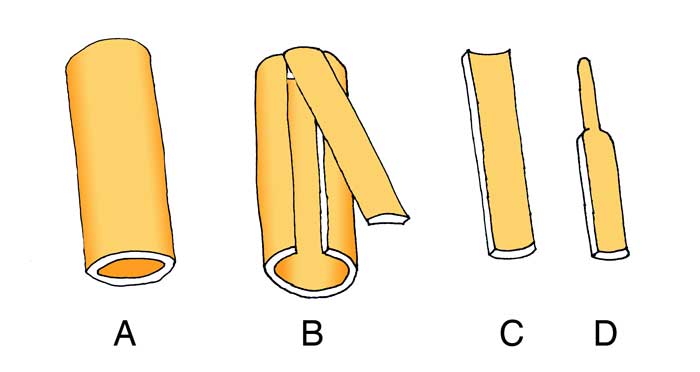

The tuning pegs are a very important part of the dotora. These are known as the “kan”. As one moves around India and Bangladesh, one may find many variations on how the tuning pegs are made. One often finds tuning pegs made of hard wood that have been turned; these are similar to those found on the sitar or sarod (see “Making the Sitar – kunti”). One occasionally may see mechanical tuners similar to those found on guitars, mandolins and modern dilrubas. These fancier tuning systems are typical of the higher priced dotoras found in many of the larger music stores of the cities. However, we will stick to the more rural roots and describe a way of making tuning pegs from bamboo.

A few words are in order concerning bamboo. As a whole, it has been said that bamboo has a strength-per-weight ratio which is greater than steel. However, one must be sensitive to the characteristics of bamboo. Parts of it are very strong, but weak areas can compromise the overall strength very significantly. For our purposes, it is sufficient to remember that the skin of the bamboo is the strongest part of the bamboo; but the skin is also very thin. This should be kept in mind when one is carving and fashioning the pegs. It is preferable not to carve too much of the skin away because this will compromise the overall strength of the peg. However carving away the inner, woodier side, will not compromise the strength as much.

To make the tuning peg, one starts with the proper bamboo. For instance, the local variety “makla” is widely chosen and found to be suitable for this purpose. One starts with a cylinder of bamboo roughly four inches in length (illustration “A” in the figure below). With a chisel one cuts out a longitudinal section that is about 1 inch in width (illustration “B” and “C” in the figure below). One then takes this section and carves it into the form shown in figure “D”. This produces a peg that has two sections. There is the handle and there is the shaft. The handle should be roughly 2.5 inches and the shaft should be roughly 1.5 inches. This is of course merely a rough guide to the proportions; the precise dimensions are determined by the size and dimensions of the muga (i.e., the peg box).

Although it is only barely noticeable, the shaft should not be cylindrical. There should be a slight taper to it. This will allow for a better control on the tension as it is fitted into the peg box (muga).

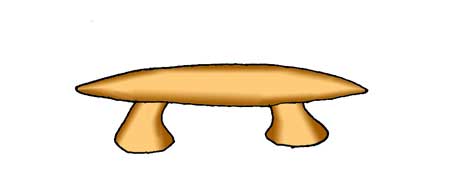

Bridge

The dotora must have a bridge. There are numerous variations in both material as well as form for the bridge. The more expensive ones available in the music stores sometimes use bridges made of camel bone. However a more rustic version would be made of wood. A wooden one may have the form as shown in the picture below.

Dotora bridge (without notches)

One should notice two things about the bridge at this point. One is that it does not have any grooves for the strings. Making the groves should be the last job and performed only when one is stringing the instrument and is able to judge a proper action. Another point to consider is that at this point the feet should be longer than required. As we start to string the dotora, then at that point we can chop the feet down and adjust the action to a comfortable level.

String Attachment at Base

There must be some provision for attaching the strings to the base of the instrument. There are almost as many ways to do this as there are instrument makers. Many of the fancier and expensive southern versions have basses made of brass or bone with projections on them allowing for the strings to be tied to. Some of the simplest forms are nothing more than tying the strings directly to the protrusion on the base of the instrument. Sometimes a nail or screw is inserted into the base; upon this the strings can be tied. In the accompanying photographs we see a simple form of akkra. This is nothing more than a small rod which is tied to a nail in the protrusion at the base. Upon this rod the strings are attached.

Finishing Touches

At this point there are a number of finishing touches that must be attended to. Let us look at them in greater detail:

One topic that needs to be addressed is the tuning pegs (kan). Ideally at this point, the tuning pegs will be slightly too large for the holes. (If this is not the case, you had better go back and make some more pegs.) Now is the time that you work on both pegs and holes to make a good fit. It is interesting to note that when you finish, you will find that a particular peg only fits well with a particular hole; so do not forget which peg goes into which hole. This is not peculiar to the dotora but is a quality which is shared by sitars, sarods and other indigenous instruments of South Asia.

Next, we roughly string the instrument and put the bridge on. There are several jobs that need to be done.

One of the jobs is to cut the notches into the bridge. This must be done by seeing how the strings on the bridge line up against the fingerboard. This may be thought of as a lateral adjustment of the string positions.

There is also a vertical adjustment of the string position. This is how high the strings are from the fingerboard. This is also referred to as the “action” of the instrument. The general rule is to have the strings as low and as close to the fingerboard as possible. However the concept of “possible” may not be intuitive. The strings should not be so low as to rattle against the fingerboard. Furthermore over time, the skin will stretch and the bridge will go down, so allowances must be made for the settling in of the skin and bridge. Although we are trying to get the action such that the strings are close to the fingerboard, they must be high enough to accommodate these other considerations.

The adjustment of the action is done by shortening the feet of the bridge. We previously mentioned that the feet should intentionally be made longer than necessary. It is at this point that we gradually cut the feet down until we obtain the right action.

Plectra

The dotar is played with a plectrum known as a “kati”. It is generally made of horn, bone, coconut shell, or wood.

Stringing and Tuning

The stringing and tuning of the dotora, like many other instruments of South Asia, is not standardised. In South Asia the stringing and tuning is considered a part of the artistic process. Therefore choices of gauge and material for the strings is often just a reflection of an individual artist’s taste. The tuning is so variable that it is very normal for the tuning to be different for each song. With these considerations in mind, we will approach the subject of stringing and tuning. It is pointless to pontificate on specific tunings, but more appropriate to discuss the philosophy and approaches to the tuning.

Philosophy of the Tuning – There are several things to consider when developing concepts and approaches to tuning the dotora. The first thing to remember is that the instrument will be tuned to an open tuning. That is to say that the strings, tension, and pitch will reflect but a single key. Most of the considerations of the stringing and tuning become clear when we keep one simple fact in mind; the dotora is there to accompany the voice. Therefore, the most fundamental issue, specifically what key to tune to, is determined entirely, according to what key the singer is going to sing in. Unlike Western music or the Western influenced film music, the singer generally does not change the key from song to song, but retains a particular key for all of their performances. Once this key is established, then everything else about the tuning falls into place.

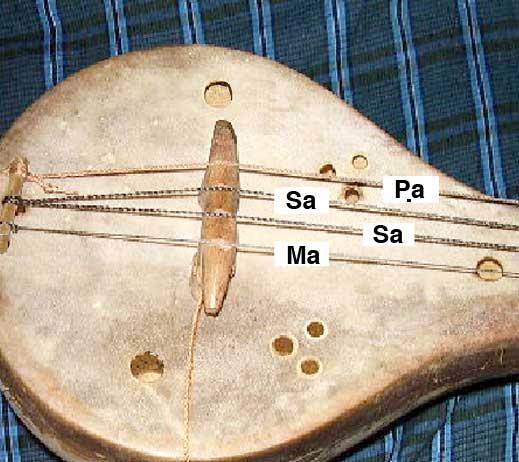

Dotoras may have a varying number of strings but the most important will be the first two strings. The outer most string is known as the jin and the next one in is known as the sur. Of these two strings the sur is tuned to the tonic (i.e., Sa, a.k.a. Shadaj, or Khadaj) and the jin will be tuned a fourth up from this tonic (i.e., Ma or Madhyam or “moddhom”). Most of ones playing will be upon these two strings. Any other strings and their tuning is generally only a reflection of the individual artist’s taste.

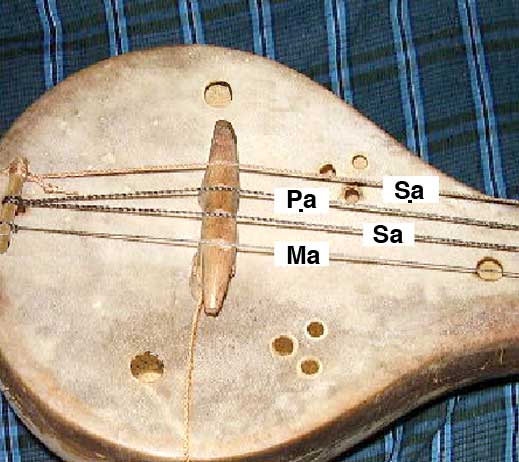

We will show two common tunings for a four-string dotora. The first is shown below:

Ma, Sa, Sa, Pa tuning

This last tuning deserves some discussion. We see that both the second string and the third string are tuned to the tonic (Sa). This effectively gives you two strings which are the sur. The fourth string is a fourth below the sur (i.e., a fifth, but in the lower octave). This corresponds to Pa (Pancham). This string is called the “Bom”. (For more information on scale structures go to: Saptak-The Scale.

There is another tuning that you should consider. This is shown below:

Ma, Sa, Pa, Sa tuning

There are a couple of interesting points to consider about this tuning. The first is that it extends the potential playing range half an octave lower than the first tuning. Although almost all of the playing is done only on the first two strings, there are occasions where you wish to explore the lower octave. In these rare cases, the extended range of this tuning can be advantageous. But, this extended range is comes by sacrificing some of the richness of the sound of the tonic that one finds with two sur strings.

Materials and Gauges of Strings – The first thing to remember about the choice of materials and the gauges of the strings is that they must reflect the overall philosophy of tuning. If you wish to tune to a particular note, it is important that the strings will actually do it. This may seem self evident, but as a practical matter this is the point that trips most people up.

As a general rule we can say that the southern versions of the dotora tend to use metal strings while the northern dotoras tend to use strings of silk, cotton, gut, or artificial fibres. This is just a generalisation, because it is normal even to find different materials mixed together on the same instrument.

We only need to keep a few things in mind when choosing strings:

- Heaver gauges (thicker strings) produce lower pitches, while light gauges produce higher pitches.

- Metallic strings produce lower pitches while gut, cotton, and silk produce lower pitches.

- Brass and bronze produce lower pitches while steel produces higher pitches.

With these simple points, you can start experimenting to find the right strings for your instrument.

Playing the Dotora

An in depth discussion of the playing of the dotora is beyond the scope of this humble web page. However there are a few things that we can mention.

The dotora has two modes of playing. The first mode treats the the dotora as though it were a rhythmic instrument. For this, there is an alternation between the sur string (Sa or the second string) and the jin string (Ma or first string). This is done in an open manner, without the use of the fingerboard. This produces the characteristic sound that is so typical of baul sangeet, (the music of the Bauls). The second mode is where the dotora is played in a melodic fashion. This is almost always upon the first two stings, and involves very intricate fingerings upon the finger board. In this mode, all the notes of the scale may be produced. Typically the dotora is played in such a way that it alternates between these two surprisingly distinct modes.

| THESE BOOKS MAY NOT BE FOR YOU |

|---|

A superficial exposure to music is acceptable to most people; but there is an elite for whom this is not enough. If you have attained certain social and intellectual level, Elementary North Indian Vocal (Vol 1-2) may be for you. This has compositions, theory, history, and other topics. All exercises and compositions have audio material which may be streamed over the internet for free. Are you really ready to step up to the next level? Check your local Amazon. |

Works Cited

Grierson, Sir Abraham

1903 Linguistic Survey of India. Office of the Superintendent of Govt. of India

Selected Video

Other Sites of Interest

Commodifying Baul Spirituality: Changing Baul Literature and Music in Bangladesh

Jaggan: Musical Heritage of Jessore District, Bangladesh

India : North Indian folk music