Tar shehanai is merely a small mechanical amplifier that has been added to an esraj. One may think of the tar shehanai as having the same relationship to the esraj as the dobro guitar has to a standard acoustic guitar. Since the tar shehanai is just a modified esraj there are really no significant differences in technique or tuning. Therefore, one can read about the esraj for more information.

History

The history of the tar shehanai is not completely clear; but from what we do know, it is an interesting story. The story actually begins thousands of miles away in Europe and the United States. Since the third quarter of the 19th century, the introduction of the gramophone saw a need to develop more efficient ways of acoustically coupling the weak mechanical energies from the disks and cylinders to the air in the form of sound. During the later part of the 19th century and well into the 20th century, such efforts begin to bear fruit in the form of extremely efficient gramophone sound boxes.

Around the turn of the 20th century, a few instrument makers began to realise that many of the same requirements of the gramophone also applied to musical instruments. Therefore, numerous instrument makers around Europe and the US almost simultaneously began to experiment with the use of gramophone sound boxes as a replacement for the more traditional wooden sound-boxes that we have come to associate with guitars, violins, and other stringed instruments.

There were a number of instruments that were based upon this approach. Today the Stroh violin is still in production. The Dobro guitar’s “pan” also evolved from technologies that were developed for the gramophone. One of the most significant for the development of the tar shehnai, was an instrument that was known as the “Japanese fiddle”.

These musical experiments we not done merely in the name of innovation; they were spurred by very real musical and commercial needs. The rapidly developing recording industry was having a very difficult time recording stringed instruments. Although some instruments such as the saxophone had a strong sound that was highly directional and could be easily recorded, most of the stringed instruments had sounds that were weak, diffuse, and non-directional. The gramophone-soundbox instruments overcame these problems and were easy to record.

These new instruments proved popular on stage as well. We must not forget that this was an age before the introduction of electronic sound amplification. The greater volume of these instruments proved to be a boon for soloists and small groups.

The movement of these instruments into India is not completely clear. It appears that in the very early days of the 20th century, these instruments found their way into south Asia. India too had a fledgling recording industry. India’s recording industry had the same technological challenges that other countries faced. It appears that the Japanese fiddle addressed these challenges in India just as it had in the West.

I am told that in the early days of the 20th century, there was a relatively common indigenous or “desi” version of the Japanese fiddle. This was a staff, usually of bamboo, that had a single string mounted to it. It was tightened by way of a peg. The string at the lower end was attached to a gramophone sound box.

The “desi” version of the Japanese fiddle came to be known as the “tar shehanai”. The term tar shehnai, literally means a “stringed shehanai“. This is an obvious reference to both the shehnai-like sound of the Japanese fiddle, and the string which is used as its sound producer.

This brings us to the next phase of evolution. These bamboo tar shehnais, may have been accessible, but they were really very crude. Someone, somewhere, got the idea of attaching the gramophone sound box to an existing esraj. When this was done the tar shehnai truly came of age.

The tar shehnai had a great popularity in the early days of the film industry. Even with the introduction of vacuum tube (valve) based electronic recording, the tar shehanai proved very easy to work with in the studio. Furthermore, the very piercing sound quality of the tar shehnai gave a certain “punch” to the musical interludes in film songs. Therefore it should be no surprise that the tar shehnai continued to be popular in film songs until about the early 1960’s. This was many decades after the introduction of the vacuum tube removed the tar shehnai’s very raison de etre.

This instrument fell into several decades of obscurity. There were many reasons for its decline. Certainly changing musical tastes were a big reason, but there was a more practical one. Gramophone sound box production essentially came to a halt. Without a reliable source of sound-boxes, the manufacture of tar shehnais could not be continued.

The last decade has seen a resurgence in interest in the tar shehnai. There are two reasons for this. Undoubtedly the greatest motivation is the growing Gurmat Sangeet movement among the Sikh community. This has turned people’s attention to instruments that in some cases have not been popular for centuries. Although the tar shehanai was certainly not extant at the time of Guru Gobinda, the basic resurgence in traditionalism has brought the tar shehnai back to people’s attention, thus saving it from extinction.

Another reason why the tar shehanai has resurged is due to the changing nature of world economies. One factor was the collapse of the Soviet Union. Gramophone sound box manufacture apparently has been continuing in some parts of Eastern Europe throughout the 20th century. The opening up of these markets, coupled with the massive reduction in India’s own trade barriers in the 1980’s and 1990’s, has created a reliable source of sound-boxes for Indian craftsmen.

So this is where the tar shehanai stands today. It is unlikely that it will ever replace the electronic keyboard or the electric guitar in popularity, but at least for the next few decades, it does not look like it will become extinct.

| Are you interested in a secular approach to teaching Indian music. |

|---|

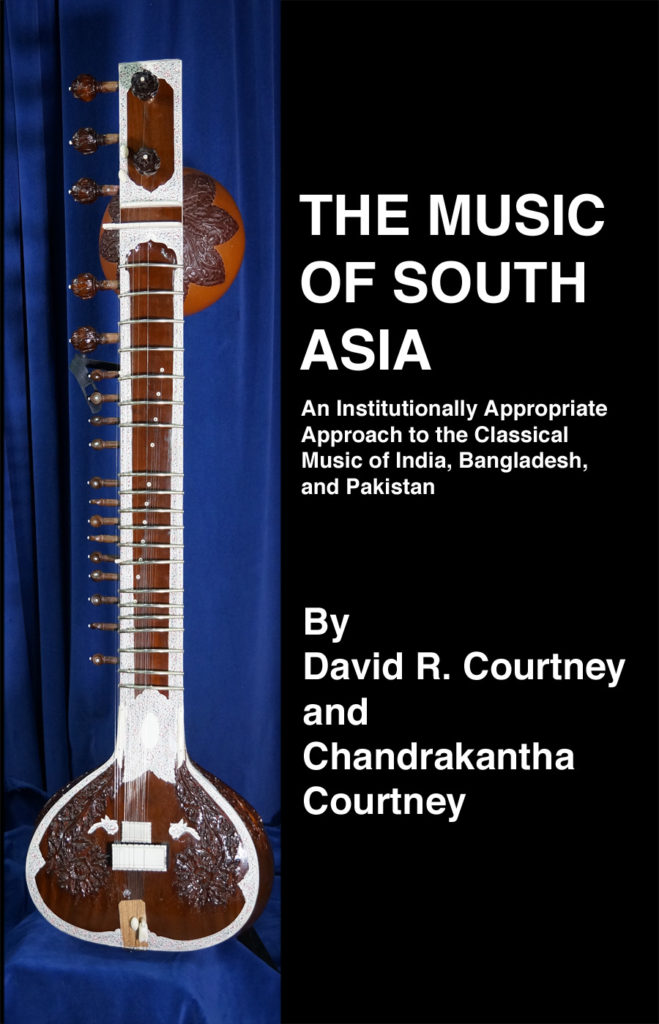

Indian music is traditional taught in a fashion that is linked to Hindu world views. But there are situations, often in schools, where this approach may not be the best. In such situations The Music of South Asia may be the best resource for you. |