| This article is only an introduction. If you would like more information please check out “Manufacture and Repair of Tabla” |

NOTE – This article previously appeared in PERCUSSIVE NOTES, Volume 23 Number 2 January 1985 pages 33-34

Reprinted by permission of the Percussive Arts Society, Inc., 701 N.W., Ferris, Lawton, OK 73507

Introduction

The ubiquity of tabla in the Indian Subcontinent is without dispute. Its variety of tonal colours gives it a flexibility seldom matched by other percussion instruments.

The complexity of its construction accounts for its versatility. This complexity reaches such a degree that only trained craftsmen can create a tabla.

I will attempt to describe the technique of tablamaking and, to a lesser extent, the men involved in this craft. Most of the terms in this article will be in the dialect of Hyderabadi, which is a vernacular form of Urdu. Other terms may also be included.

Tabla is the preferred instrument for the, entire Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent. It is used in classical as well as light folk and dance music. Only in the South Indian classical system (Carnatic Sangit) is its use discouraged.

Tabla consists of a small wooden drum called sidda (tabla, dayan, or dahina) and a larger metal one called dagga (banya). The sidda is played with the fingers and palm of the right hand, while the dagga is played with fingers, palm and wrist of the left hand. The pair of tabla is positioned on two toroidal bundles called chutta, consisting of plant fiber wrapped in cloth.

The creation of tabla is such a refined art that a single individual never handles all aspects of its fabrication; rather, four separate industries have evolved. These are 1) Fashioning of the wood; 2) fashioning of the metal; 3) preparation of shai massala; and 4) final assembly.

The Craftsmen

The main craftsmen fall into the last category and are known as tablawalas. The majority of tablawalas in the Hyderabad area are Muslim and, invariably, they occupy a lower segment of society. Not only do all tablawalas occupy the same segment of society, but also one tablawala even stated that the majority of the craftsmen in the area are related either by blood or marriage.

Tablawalas work in shops known as tabladukhans, which are always very small and crowded, allowing only the minimum space necessary for work. The shops tend to be clustered together, so it is not unusual to see three or four such dukhans on the same block. As a matter of general interest, it may be added that this is not just a characteristic of tablawalas but also applies to all Indian crafts, such as goldsmiths, silversmiths, saree sellers, etc.

The tablawalas of Hyderabad deal in four types of drums: tabla, dholak, dholki (nal), and maddal (small size pakhawaj.).

Let us now take a look at a typical tablawala:

Abdul Rehaman, age 55, was born in Hyderabad into the Suni sect of Muslims. His father was a skilled player of tabla as well as a craftsman, but he died while Abdul was still quite small and the task of training him fell to his father’s older brother, who was also skilled in the craft of tablamaking. At the age of ten, therefore, Abdul began his apprenticeship, which lasted five years. He married at the age of 30.

Today Abdul owns his own shop. He has two daughters and one son. The son is also skilled in the craft of tablamaking and will eventually take over the business.

| ARE YOU INTERESTED IN HOW THE TABLA IS MADE? |

|---|

This is the third volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Manufacture and Repair of Tabla |

Making of Tabla

It has already been mentioned that tablamaking involves several different industries. Each industry is handled by a different class of people with different skills.

The first step in making the sidda is fabrication of the wooden shell. This shell is known as lakadi and its fabrication is done by people whose sole job is woodcrafting.

Any wood may be used for tabla siddas; however, only a few kinds are known to make good ones. These are teak, rosewood and, occasionally, jackwood. The primary characteristics, which make these woods good, are resistance to insects and the extreme weight of the wood.

It stands to reason that the manufacture of good shells is going to be restricted to the areas which have an abundance of good wood, but if a lower quality of wood must be used, then the basic criteria for its selection and the method of fabrication remain the same.

Physical Dimensions – The wood must have a diameter and length sufficient to make a drum. The tabla lakadi must have a diameter of approximately 6″ to 8″, with a length of not less than 10″ to 12″.

Cracks – Another important aspect to consider in determining the acceptability of the wood is whether or not it has any cracks. Cracks invariably will occur in the direction of the grain and may be caused while the tree is alive or after the tree has been hewn. Either case lowers the wood’s acceptability.

Insects – Insects are another important consideration. This is especially important in determining the life of tablas made of inferior quality woods, such as mango (aam). Parasitic insects can reduce a musical instrument to dust within a few years in the warm Indian climate.

Knot Holes – The presence of knotholes in the wood is also of major importance because there is a tendency for knotholes to crack, or even disintegrate, during the seasoning process. In addition, filling these large holes always presents problems.

Weight – The weight is probably the most important aspect of the wood in determining the tonal quality of the drum. A light piece of wood will produce a thin sound, while a heavy piece of wood will produce a deep, melodious sound.

The reason for this strong effect of the wood’s weight is simple. It is not merely the head (puddi), which vibrates, but the entire body as well. This phenomenon may be easily demonstrated by comparing the sound of a tabla which can vibrate freely in the cushioned chutta with the sound of one which is resting on a stone floor.

Once the wood has been selected it is roughly chiseled into the desired shape and is placed on a lathe. The lathe completes the job of shaping the wood and, also, carves the grooves which are a characteristic decoration of all Indian drums.

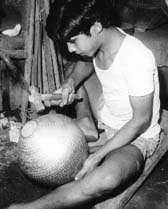

The lakadi is then removed and the process of hollowing begins. It is hollowed out by using simple gouges and chisels. Sometimes (although rarely) a machine is used to complete the boring process. A large portion at the bottom of the drum is left intact so that the weight of the wood is as great as possible (fig. 1).

The wood is now ready for seasoning, which simply involves placing the wood in a cool, dry place for a period of up to two years. The purpose o seasoning is to allow the wood to dry out. This drying process must be done as slowly as possible or cracks will develop.

The Metal Shell

The second industry involved in the making of tabla is the manufacture of metallic shells for making daggas. (There are exceptions to the metallic shells. In the area of West Bengal, for instance, they are made from fired clay. Antique daggas were fashioned from wood.) This is actually a side business of the brass-smith, whose main products are plates and vessels. The metals used in the construction of dagga shells are copper, brass, steel, and rarely, aluminium. The preferred metal by far is brass.

The construction begins when a disc of brass is cut so that it has a diameter of roughly 8″. This is then beaten into the shape of a bowl (fig. 2).

Next, a rectangular piece of brass is cut and joined together so that a cylinder with a diameter of approximately 10″ is formed. The two ends are joined by crimping, then the process of rounding it off by beating it with a mallet begins.

Once it has been rounded enough it is joined to the bowl-shaped bottom, thus: two slits are cut every half inch around the bowl so that it may be crimped and welded together by applying a mixture containing a metallic powder called dag, then heating the whole to a red heat.

The rim must then be formed by taking a strong iron ring of about 9″ in diameter and folding the brass rim over it.

Now is the time for the final shaping to be done. It is in this stage that the raised disk at the bottom is made (fig. 2). It is also in this stage that the entire shell is rotated and beaten all over so that the entire surface is dented (fig. 3). The result is a shell which has a fish-scale-like surface.

The shell is now put on a lathe and polished until all the dents are gone, then plated with chrome (fig. 4). The dagga shell is now complete.

Shai Massala

The black spot on the Indian drum is the most important component in determining its tonal colour. This black spot, known as shai (shahi, gaab, or ank) contains a commercially available black powder known as shai massala (literally, ink powder, or ink mixture). It is acknowledged in the Hyderabad area that the superior quality massala comes from Bhavnagar in the State of Gujarat.

Unfortunately, the exact manner of its preparation is cloaked in secrecy, the knowledge being transmitted from father to son for generations. It can safely be said, however, that it is a mixture of metallic dust (probably iron), soot and various plant extracts.

| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the first volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Fundamentals of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Final Assembly

We are now brought to the last and most important phase. This final stage is done by the craftsmen whose sole job is the fabrication of the tabla; the tablawalas.

Selected Video

| This book is available around the world |

|---|

Check your local Amazon. More Info.

|