Note – This article originally was published in Percussive Notes, Vol. 33, No. 6, December 1995, page 32-45.

Reprinted by permission of the Percussive Arts Society, Inc., 701 N.W., Ferris, Lawton, OK 73507

Introduction

The tabla is a well known percussive instrument from the Indian subcontinent, yet the nature of compositional theory for this instrument is little known. This is unfortunate because the theory is remarkably advanced and the tabla has become a source of inspiration to modern percussionists throughout the Western world (Bergamo 1981). There are only two approaches to Indian rhythm; cyclic and cadential (Stewart 1974). The cadential form requires a resolution while the cyclic form rolls along and does not resolve. The cyclic form includes such common examples as theka, rela, or kaida. These will be covered in this paper.

Background

It is necessary to go over a little background before we delve into our discussion of the cyclic form. First, there are different criteria used for the nomenclature. We also need to bear in mind the relationship between tabla and its progenitor, the pakhawaj. We need to be aware of the stylistic schools (gharanas). There are a few concepts of Indian rhythm which must be mastered. Finally, we should know what the cyclic-form is, and how it relates to the cadential form.

Tabla is derived from an ancient barrel-shaped drum known as pakhawaj. This drum supplies a large body of compositions for the tabla. Additionally, the pedagogy, the system of bols (mnemonic syllables)(Courtney 1993), and musical tradition has been taken almost without change from the pakhawaj.

The system of pedagogy has a special significance for tabla. Over the millennia, musical material has passed from the guru (teacher) to the shishya (disciple) in an unbroken tradition. This has created stylistic schools which are known as gharanas. These gharanas are marked by common compositional forms, repertoire, and styles (Courtney 1992).

The fundamentals of the Indian system of rhythm are important. This system, known as tal is based upon three units. These are the matra, vibhag, and avartan; which refer to the beat, measure and rhythmic cycle respectively. The vibhag (measure) is important because it is the basis of the timekeeping. In this method, each measure is specified by either a clap or wave of the hands. The Indian concept of a beat is not very different from the Western, except for the first beat. This first beat, known as sam, is pivotal for all of north Indian music. Aesthetically, it marks a place of repose. It also marks the spot where transitions from one form to another are likely to occur.

Although there are many compositional forms, there are really only two overall classes; cyclic and cadential. These mutually exclusive classes are based upon simple philosophies. The cadential class has a feeling of imbalance; it moves forward to an inevitable point of resolution, usually on the sam. It is a classic case of tension/resolve. Common cadenzas are the tihai, mukhada, paran. In contrast, the cyclic class comprises material which rolls along without any strong sense of direction. One may generally ascribe a feeling of balance and repose to this class. These include our basic accompanying patterns (theka and prakar); formalized theme and variation (kaida); and a host of others which we will discuss in greater detail later in this paper.

The alternation between the cyclic and the cadential material is the aesthetic dynamo which drives Indian music forward. The cyclic material is the groove or rhythmic foundation upon which the main musician builds the performance. The stability of the cyclic form makes it suitable for providing the musical framework for either tabla solos or accompaniment. Conversely the tension and instability of the cadenza provides the energy to keep the performance moving.

The conceptual basis of the terminology is important. The nomenclature can be confusing until we realize that terms may be based upon unrelated criteria. This is illustrated with a simple analogy. Imagine a Martian suddenly appearing in human society, whose job is to categorize the various types of people. On different occasions, he may see the same individual being referred to as a Republican, Catholic, male, middle executive, or a host of other labels that we apply to people everyday. The situation is very confusing until our Martian realizes that these labels are based upon unrelated criteria.

This is the same type of confusion which is present in the terminology of tabla. There are several criteria used to define compositions. These criteria are: bol (mnemonic syllables), structure, the function, and in rare cases the technique. The bols are the mnemonic syllables; cyclic material cuts across the spectrum, so any and every bol of tabla may be found. The structure is the internal arrangement of patterns. There are a number of possible structures used in cyclic material but a binary/ quadratic approach is especially common. In this method, the first half is commonly referred to as bhari while the second half is referred to as khali. It is interesting to note that while our cyclic material is commonly based upon a quadratic / binary structure our cadential material is usually triadic. The function of cyclic material is the actual usage within the performance. Material may function as an introduction, a simple groove, a fast improvisation, or any other function. The technique is the rarest criterion. Sometimes the technique is one-handed, two-handed, or verbal.

These are the six points which should be remembered from this brief introduction. 1) The nomenclature is based upon different criteria, therefore it is usual to find a single composition bearing different names. 2) Much of the material and philosophy has been derived from an ancient two-headed drum called pakhawaj. 3) Indian rhythm uses the concepts of cycle, (avartan), measure (vibhag), and beat (matra). 4) The measures are represented by a style of timekeeping based upon the clapping and waving of hands. 5) The first beat of the cycle, called the sam, is a pivotal point for the music. 6) There are two overall philosophies for the material: cyclic and cadential. The cadenza is a tension / resolve mechanism while the cyclic form is the basic “groove” characterized by a feeling of balance. Some of our readers may have a difficult time absorbing all of these concepts at once. The unfamiliar terms are especially difficult for the newcomer. We are including a glossary at the end of this article to make the subject more accessible. We may now proceed to the discussion of cyclic compositions.

| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the first volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Fundamentals of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Compositions

There are a number of compositional forms which may be considered cyclic. The ka, prakar, kaida, rela, gat, laggi and a few other forms will be discussed. Although these terms may be new to the average reader their importance will become clear.

Theka – Theka is the accompaniment pattern used for Indian music and is the most basic cyclic form. The word “theka” literally means “support” or “a place of rest” (Pathak1976). Whenever one is accompanying a vocalist, dancer, or instrumentalist, one will spend most of the time playing this. Theka is defined entirely by its function. It is the major accompaniment pattern for north Indian music. Any bol may be found but, Dha, Na, Ta, Tin and Dhin are common. Any structure imaginable may be found, but a binary structure (i.e., bhari khali) is quite common.

Theka has become inextricably linked to the fundamental concepts of tal. In northern India, when one speaks of tintal, rupak, or any other tal, one is generally speaking of the theka. It is common for several north Indian tals to have the same number of beats, same arrangement of the vibhags, and the same timekeeping (i.e., clap/wave patterns), yet be distinguished by their thekas. This is unthinkable in south Indian music. This link between the performance (e.g., theka) and the theoretical (e.g., tal) can make an in-depth discussion difficult. Many of the points which are often raised in discussions of theka should more correctly be discussed in general discussion of north Indian tal. It is for this reason that we will not go into greater detail about vibhag, avartan, etc.

Here are a few common thekas.

1. Tintal theka

2. Rupak theka

3. Kaherava theka

4. Dadra theka

Prakar – The prakar is the variation or improvisation upon the theka. When a musician refers to “playing the theka” he is actually referring to the prakars. This is because a basic theka is too simple and dull to be used in any degree on stage. There are a number of ways to create these these variations; yet the most widespread are the ornamentation and alteration of the bols.

Ornamentation is the most common process for generating prakars. This keeps the performance varied and maintains the interest of the audience. The basic theka is a mere skeleton, while the prakar puts the flesh onto it. We can illustrate this with these two examples of dadra:

Basic Dadra (theka)

Prakar of Dadra

The difference in moods between these two examples is clear. The first example has a childlike simplicity and becomes monotonous after a while. Conversely, the second example is more lively. It is important to keep in mind that this is nothing more than the original theka with some ornamentation. On stage, this prakar would be mixed in with an indefinite number of similar improvisations to keep the performance moving at a lively pace.

Ornamentation is not the only process, for many times a prakar is formed by a complete change in the bols. This is usually done for stylistic reasons. Compare the basic kaherava with a prakar which is sometimes referred to as bhajan ka theka.

Basic Kaherava (theka)

Prakar of Kaherava (Bhajan Ka Theka)

The relationship between this pair of kaheravas is very different from the relationship seen in our dadra examples. The basic bols of kaherava are not contained in bhajan ka theka. This prakar represents a totally different interpretation. When there is a restructuring of the bols it is sometimes called a kisma.

We have seen that prakar is the variation upon the theka. This may be a simple ornamentation or it may be a totally different interpretation of the tal. There are numerous processes behind the generation of these patterns but we are not able to go into them here. An in depth discussion may be found elsewhere (Courtney 1994b).

Kaida – Kaida is very important for both the performance and pedagogy of tabla solos. The word Kaida means “rule” (Kapoor, no-date). It implies an organized system of rules or formulae used to generate theme and variations. It originated in the Delhi style (i.e., Dilli gharana) but has spread to all the other gharanas. In the Benares style it is referred to as Bant or Banti (Stewart 1974). Attempts are occasionally made to distinguish kaida from bant. Such attempts usually are motivated by a chauvinistic attitude toward particular gharanas and are not based upon any objective musical criteria. The results of these efforts have been musically insupportable.

Kaida is defined by its structure. It is a process of theme and variation. Any bol may be used, so the bol has no function in its definition. It is also hard to consider function as a defining criteria. Kaida may be thought of as a process by which new patterns may be derived from old. We will illustrate this with a well known beginner’s kaida. (Most kaidas are excruciatingly long, so this short one will suffice.)

Theme

Theme (full tempo)

Variation #1

Variation #2

Variation #3

Tihai

It has already been stated that the word “kaida” means rule, so it is convenient for us to go over the rules. This last example will serve to illustrate it.

The first rule of kaida is that the bols of the theme must be maintained. In other words, whatever bols are contained in the main theme are the only ones that can be used in the variations. A brief glance at our example easily bears this out. However let us go beyond a mere glance. Close examination reveals that the syllable Ti suddenly appeared in the third variation. It is clearly a variation of Ti , which was present from the beginning. If one thinks in English then this subtlety will be missed, but if one thinks from the standpoint of North Indian languages this becomes a major alteration. Tabla bols show a tremendous tolerance in their vowels (i.e., swar) but show very little tolerance in their consonants (i.e., vyanjan). Although this is an interesting topic it is not possible to go into it in any depth in this paper.

Another rule of kaida concerns its overall structure. It must have an introduction, a body and a resolving tihai. The introduction is usually the theme played at half tempo, yet one may hear introductions which involve complex counter-rhythms (i.e., layakari) and even basic variations upon the theme. The body consists of our main theme played at full tempo and the various variations. It must finally be resolved with a tihai. The tihai is essentially a repetition of a phrase three times so that the last beat of the last iteration falls on the first beat of the cycle (i.e., sam). The tihai is discussed in much greater detail elsewhere (Courtney 1994a).

It is also a rule that everything must exhibit a bhari / khali arrangement. This means that everything must be played twice. The first time should emphasize the open, resonant strokes of the left hand while the second iteration should emphasize its absence. Only the tihai is exempt from this restriction because the tihai is not really a part of the kaida but rather a device used to resolve and allow a transition.

It is also a rule that the variations must follow a logical process. Kaidas have a number of variations, which may be called bal, palta or prastar. (There are many languages in use in northern India so terminology may vary.) The particulars of a logical process often vary with the gharana (stylistic school) and individual artistic concepts. Therefore the process illustrated in the previous example is typical but not the only possible approach. In our main theme, both slow and full tempo, we find a rhyming scheme being built up. Dha Dha Ti Ta and Ta Ta Ti Ta will be assigned a code which we can arbitrarily call “A” , while Dha Dha Tun Na and Dha Dha Dhin Na we can call “B”. Therefore, the main theme has the rhyming scheme of AB-AB. If we move to the first variation we see that it takes the form of AAAB-AAAB. In a similar manner the second variation has the form of ABBB-ABBB. One could continue to build up other reasonable structure such as AABB-AABB or any other reasonable permutation. Notice that each iteration (i.e., bhari / khali) usually ends with the B structure, therefore the B begins to function as a mini-theme. This too is subject to some variation because in some gharanas, particularly the Punjabi gharana it is not the entire B but a fraction thereof which functions as the mini-theme.

Mathematical permutations based upon only two elements are limited so other processes need to be included. One approach is to double the size of our structure. Instead of working with structures like AAAB-AAAB we could work with AAAAAAAB-AAAAAAAB. Doubling the size certainly increases the possible permutations, but can quickly become unmanageable; therefore many gharanas do not do this. A more universal approach is to take the A and B patterns and fragment them to create smaller structures.

Fragmentation may be seen in the third variation of our example. We have derived the expressions Dha Ti Ta and Dha Ti from Dha Dha Ti Ta . For convenience we will call them “C” and “D” respectively. Therefore, variation number three may be expressed as CCDAB-CCDAB. Now that it has been fragmented, we can generate patterns like CDCAB-CDCAB, DCCAB-DCCAB, ACDCB-ACDCB, etc. The use of fragmentation to derive new structures, and their subsequent recombination is a far more flexible process. It is not surprising that this process is used throughout northern India.

The fact that kaida is defined by structure has interesting ramifications. It gives rise to a whole family of subdivisions. If the bols of rela are used, a form known as kaida-rela is created. In the same manner kaida-laggis, kaida-peshkars, and kaida-gats are also produced by the use of the appropriate bols.

We may summarize our discussion of kaida by saying that it is a structural process of theme and variation. This process is governed by rules which may be briefly summarized as follows: 1) an overall structure of introduction, body, tihai, 2) a binary (i.e., bhari / khali) and quadratic (i.e., AB-AB) structure, 3) maintenance of the bols of the theme. 4) an organized process of permutation. This process may be applied to any bol. With these processes understood we may move on to other material.

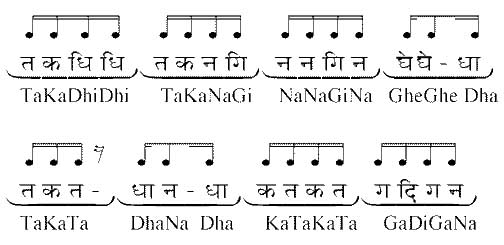

Rela – The word rela means a “torrent” , “an attack” (Pathak1976) or ” a rush” (Kapoor no-date). It is has been suggested that the word is derived from the sound that a railroad train makes, however this is generally not accepted in academic circles. Rela is defined by the bol. One normally finds pure tabla bols used, as opposed to bols from the pakhawaj. Here is a representative, but certainly not exhaustive, list of the bols used in rela.

Rela

These bols function as basic building blocks from which larger patterns are assembled. Structure is not a criterion for rela‘s definition, therefore the bols may be assembled in a many ways. If we develop it according to the rules of kaida it is usually referred to as kaida-rela. If we assemble them in a freeform manner it is sometimes referred to as swatantra rela. The concepts of swatantra and kaida may be viewed as two extremes of a continuum. The performance of rela is usually somewhere in between these two extremes. In other words some of the rules of kaida may be followed but not all. This is up to the individual artist and is not specified by the concept of rela.

Gat – The gat originated in the purbi styles (e.g., Lucknow, Farukhabad and Benares gharanas), but today it is played throughout India. It is defined both by function and bol. Functionally, it is a fixed composition rather than any improvisation (Shepherd 1976). Viewed from the standpoint of the bol, it shows a moderate influence of pakhawaj, as do most purbi compositions.

Gat is a very difficult topic to discuss because it is so poorly defined. The word gat literally means motion, however the musical meaning implies a fixed composition of either cadential or cyclic form. A survey of the Hindi literature shows that virtually any tabla composition of the purbi class can be called a gat. It is perhaps easier to say what a gat is not. It is not a pakhawaj composition (i.e., paran, fard, sath etc.), nor is it a light style (e.g., laggi) nor is it an accompanying style (e.g., theka or prakar) nor can it be improvised. This does not narrow the definition very much. Gat is a broad class of compositions rather than a single compositional form. We will now look at at some of these forms.

The kaida-gat is a common form. As the name implies it is the use of purbi bols in a theme and variation process which follows the rules of kaida. Therefore, the AB-AB structure is central to the process. The kaida has already been discussed, so the aforesaid rules need not be restated.

An extremely common form of gat uses a quadratic structure but cannot be considered a kaida. This follows an ABCB structure. This is occasionally referred to as domukhi, or “two faced”, in reference to the two B patterns. Some gharanas will also call it a dupalli, yet many dupallis are cadential rather than cyclic. Unlike the kaida-gat, there need be no introduction nor do there have to be any variations. One may play the same gat any number of times. A tihai is usually used, but this is merely a reflection of universal custom rather than anything inherent to the gat. Here is a one example (Saksena 1978:59):

Gat

There are also gats which have a repetition of a phrase three times. The cyclic version usually follow an ABCBCB or ABCBDB structure. This type is sometimes called tinmukhi or tipalli. However, it should be noted that the term tipalli usually refers to a cadential form and is thus outside the scope of this paper (Courtney 1994a).

If a similar approach is taken but the “B” structure is repeated four times it may be called a chaupalli. Sometimes it need not be an entire structure but a single stroke (e.g., Dha Dha Dha Dha)( Sharma 1973). Again many chaupallis are cadential.

The lom-vilom is another fascinating form of a gat. It is a musical palindrome that is the same whether played forwards or backwards. It is a characteristic of the palindrome that there are two halves. The first and second halves must be mirror images of each other. The first half of the lom-vilom is called the aroh (ascending), while the second half is called the avaroh (descending). Here is an example (Shankar 1967:145).

Lom-vilom (ascending)

(descending)

There are other forms which are considered to be gats by many musicians but will not be discussed here. These are the chakradar gats, tipalli, chaupalli, and dupalli. We will not discuss them because they are cadential forms and do not fall within the topic of this paper.

Peshkar – Peshkar has a number of interesting characteristics. It often uses interesting counter-rhythms (layakari) and has a fully developed process of theme and variation. If the process of theme and variation follows the rules of kaida then it is called kaida-peshkar. Often substitution processes are used which, although logical, violate basic rules of kaida. In such cases it is simply referred to as peshkar.

Laggi – The laggi is a light form of aggressive accompaniment. Some musicians define laggi by its function and others define it by its bol. Therefore the form of laggi my vary tremendously from artist to artist. When laggi is defined by function, one may find almost any bol used. Bols of rela may be used with patterns derived from folk or kathak traditions. This style is inherently freeform so it is difficult to make generalizations concerning bols or structure. This freeform approach is emerging as the dominant definition of laggi for modern performances. When laggi is defined by the bol, it is usually based upon the use of fast, open, resonant strokes. This definition is still used for pedagogic purposes although it is falling out of fashion for performance. Common bols for laggi are:

Laggi

The definition of laggi by bol has an interesting ramification. It allows us to develop the bols in a strict kaida format. This would at first appear to be a stylistic mismatch because kaida is used in formal situations while the laggi is used in light performances. Still, the use of a kaida-laggi gives another color to tabla solos.

Minor Forms – We have already covered the major cyclic forms, yet there are a number of minor forms. We will consider a form to be minor if it meets one of three criteria: 1) it is not played by all of the gharanas, 2) it is seldom performed, or 3) there is substantial disagreement as to the definition. The sath, rao, thappi, ekhatthu, dohatthu, stuti, and chalan fall within this category.

Thappi – Thappi is the form of accompaniment which was common in the old pakhawaj style. The thappi is so similar to theka that most musicians call it theka. The important difference is that thappi does not define the tal while theka does. The most well known thappi is the bol for choutal:

Thappi

Fard and Sath – Fard and sath are two forms of cyclic material. They are composed of only a single structure. The bols of sath and fard are exactly the same, the only difference is function. Sath is an aggressive form of accompaniment of the old pakhawaj tradition while fard is a solo piece found in the Benares tradition. This difference is largely insubstantial and fard may be merely the Benares name for sath. One may even hear of these forms as being referred to as paran, however, most people consider the common form of paran as cadential and therefore out of the scope of this paper.

Ladi – Ladi or rao are poorly defined forms which impinge upon both rela and laggi. Many artists and gharanas do not even use the terms. The only thing that can be said with any certainty is that they are fast improvisations in a cyclic form.

Chalan – Throughout India musicians say they play chalan. Unfortunately what they play may be so dissimilar that it is hard to make a definitive statement as to what chalan is. Many consider it to be a variation of kaida (Kippen 1988). The only thing that can be said with certainty is that it is a cyclic form.

Ekhatthu & Dohatthu – It has already been said that the most common criteria for defining tabla forms are structure, bol, and function (Courtney 1994a). However in very rare cases technique is a defining criterion. This is what defines the ekhatthu, dohatthu, and stuti. Ekhatthu is a style of performance where only a single hand is used. This is used for special effect in tabla solos. The term ekhatthu means “single-handed”. Ekhatthu may be executed in any form so it is not strictly cyclic in nature. Dohatthu is a style of performance where two hands are used on the same drum. The word dohatthu means “two-handed”. The dohatthu is sometimes referred to as a “lalkila ” composition. The term “lalkila” is said by some to allude to the up and down motion of the nagada players on the walls of the Red Fort. Unfortunately the term lalkila means different things to different people (Vashishth 1977). It is probably better to avoid this term, due to the lack of agreement as to a correct definition. Dohatthu may be used for any compositional form so it is not strictly cyclic in nature.

| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the fourth volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Focus on the Kaidas of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Summary

We have seen that the mass of compositional forms for the Indian tabla fall into two classes; cyclic and cadential. The cadenza moves toward a specific point of resolution while the cyclic material is characterized by a sense of balance and repose. The common cyclic forms are the kaida, theka, peshkar, gat, laggi and rela. There are other minor forms, but in cases the minor forms are mere variations. It must be remembered these types are defined by unrelated criteria. These criteria most are structure, function, bol and in rare cases the technique. Since different criteria are used, it is common to find compositions which satisfy meet two definitions. Kaida-rela, kaida-gat, and kaida-peshkar are just a few the cyclic forms are the backbone of the rhythm of north Indian music. An understanding of this form gives a good view of the common examples. Collectively, the very soul of the music.

Glossary

Ajrada – A town in northern India, origin of one of the tabla gharanas.

aroh – The ascending sequence of a lom-vilom (palindrome) gat.

avaroh – The descending sequence in a lom-vilom (palindrome) gat.

avartan – A cycle.

bal – A variation in a kaida (theme and variation).

bant – Another name for a kaida.

banti – Another name for a kaida.

Benares – A town in northern India, origin of one of the tabla gharanas.

bhajan ka theka – A variation of kaherava.

bhari – The first half of a binary structure, characterized by full resonant strokes of the left hand drum.

bol – The mnemonic syllables

cadential form – A passage or composition which is marked by tension and release, usually resolving upon the first beat of the cycle.

chakradar – A type of tihai where a passage is repeated nine times.

chalan – A type of cyclic form.

chaupalli – 1) A cyclic form of the gat variety characterized by a passage repeated four times. 2) A cadential form characterized by a passage repeated four times.

choutal – An ancient 12-beat tal, formerly played on pakhawaj.

cyclic form – A passage or composition characterized by a sense of balance and repose.

dadra – A tal of 6 beats.

Dilli – (Delhi) A town in northern India, origin of one of the tabla gharanas.

dohatthu – Any form where two hands play on the same drum

dupalli – 1) A cadential form based upon the repetition of a phrase twice. 2) A domukhi.

ekhatthu – A composition which uses only one hand.

fard – A composition played by Benaresi tabla players similar to sath

Farukhabad – A town in northern India, origin of one of the tabla gharanas.

gat – A strictly-composed form played in a purbi style.

gharana – A stylistic school.

guru – Teacher

Hindi – The most common language in Northern India.

Kaherava – A common tal of eight beats.

kaida – A formalized system of theme and variation.

kaida-gat – The bols of a gat developed in a strict kaida form.

kaida-peshkar – The bols of peshkar developed in a strict kaida form.

kaidas-laggi – The bols of laggi developed in a strict kaida form.

kisma – Variations upon the theka.

ladi – A light style similar to rela or laggi.

laggi – A light aggressive form of accompaniment found in light and semiclassical music.

layakari – Counterrhythms.

lom-vilom – A musical palindrome (It is the same when played backward or forward)

Lucknow – A town in northern India, origin of one of the tabla gharanas.

matra – The beat

mukhada – A cadential form, usually a simple flourish resolving upon the first beat of the cycle. nagada – A large pair of kettle drums played with sticks.

pakhawaj – An ancient barrel shaped drum with heads on both sides.

palta – The variation in a kaida (theme and variation).

paran – A cadential form based upon the bols of pakhawaj.

peshkar – A type of theme and variation used to introduce a tabla solos.

prakar – The variations upon the theka.

prastar – The variations of a kaida (theme and variation).

Punjab – A province in northern India, origin of one of the tabla gharanas.

purbi – literally “eastern”. The style of playing which originated in the Eastern part of the old Mogul empire. (i.e., Farukhabad, Benares, and Lucknow).

rao – A fast accompaniment similar to laggi or rela.

rela – The very fast manipulation of small tabla bols.

Rupak – A tal of seven beats.

sam – The first beat of the cycle.

sath – A pakhawaj piece which was used in the old days as accompaniment but today is a fixed composition, similar to fard.

shishya -Student.

stuti – A piece which uses words instead of tabla bols (e.g., bol paran).

swar – The vowels in the Sanskrit or Hindi alphabet

tabla – The main percussion in northern India, consisting of a pair of drums.

tal – 1) The Indian system of rhythm. 2) An Indian rhythmic pattern.

thappi – An accompaniment form of the old pakhawaj.

theka – 1) The fundamental rhythmic pattern used for timekeeping. 2) A type of theme and variation, similar to peshkar, used by musicians of the Benares gharana.

tihai – A cadential form based upon the repetition of a phrase three times ending on the first beat of the cycle.

Tintal – A very common rhythmic cycle of 16 beats.

tipalli – A type of tihai or gat in which has each phrase is in a different tempo.

vibhag – A measure or bar.

vyanjan – The consonants in the Hindi or Sanskrit alphabet.

| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the second volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Advanced Theory of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Works Cited

Bergamo, John

1981 Indian Music in America. Percussionist. Vol 19, #1, November 1981: Urbana IL. Percussive Arts Society.

Courtney, David R.

1980 Introduction to Tabla. Hyderabad, India. Anand Power Press.

1992 “New Approaches to Tabla Instruction”. Percussive Notes. Vol 30 No 4: Lawton OK: Percussive Arts Society.

1993 “An Introduction to Tabla. Modern Drummer”. October: Modern Drummer publications.

1994a “The Cadenza in North Indian Tabla”. Percussive Notes. Vol 32 No 4, August: Lawton OK: Percussive arts Society. pp.54-63.

1994b Fundamentals of Tabla. Houston. Sur Sangeet Services

Kapoor, R.K.

-no date-Kamal’s Advanced Illustrated Oxford Dictionary of Hindi-English. New Delhi: Verma Book Depot

Kippen, James

1988 The Tabla of Lucknow: A Cultural Anaylysis of a Musical Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Saksena, Maheshnarayan

1978 Tabla Parichay, Tal Ank. Hatharas, India: Sangeet Karyalaya.

Sharma, Bhagavat Sharan

1973 Tal Prakash.Hatharas, India: Sangeet Karyalaya.(5th edition)

1975 Tabla-shiksha, Vadhya-Vadan Ank. Hatharas, India: Sangeet Karyalaya.

Shepherd, F. A.

1976 Tabla and the Benares Gharana. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International. (Ph.D. Dissertation)

Stewart, Rebacca M.

1974 The Tabla in Perspective. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International. (Ph.D. Dissertation)

Pathak, R.C.

1976 Bhargava’s Standard Illustrated Dictionary of the Hindi Language.Varanasi, India: Bhargava Bhushan Press.

Vashisht, Satya Narayan

1977 Tal Martand. Hathras, India: Sangeet Karyalaya.