(A.K.A., Kinnara, Kinnara Vina)

Introduction

The kinnari vina (a.k.a. kinnari, kinnara, or kinneri vina) is a very rare instrument of India. It is a stick zither that has three gourd resonators. At one time it was very common, but today is found only in folk music of Southern India.

Etymology – Kinnara

The term kinnari is inextricably linked to the Kinnara of Asian mythology. These mythical beings are common to Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist traditions (Saletore 1985). In the pantheon of Hindu demigods, they represent celestial musicians and dancers who are very similar to the Gandharvas (Menon 1995). Although originally of South Asia, due to the Buddhist influence, myths of the kinnara have spread throughout Asia.

The term kinnara and kinnari are virtually interchangeable. Kinnara refers to a male demigod, while kinnari refers to a female. Additionally kinnari indicates the adjective form of a word in Hindi.

These demigods are frequently depicted as being a cross between human and animal. They may be depicted with human forms, but may also be depicted as being a combination of various birds, animals, or fish. According to some traditions, they are humans who periodically transform themselves into animal forms. Among the Buddhist traditions they are usually portrayed as having the upper torso of a human, but a lower body of a bird. (Cunningham 1879).

The abode of the mythical Kinnara is said to be in the Himalayas.

It has been suggested that the real Kinnara were an extinct tribe that has become wrapped in legend and myth. According to some scholars they lived in the Swat Valley in what is present day Pakistan. (Saletore 1985)

History and Morphology

Mixing the history of the kinnari, and a discussion of its morphology is not the way that I initially intended to deal with the subject. But it’s structure and even perhaps its basic definition, have undergone such an unusual degree of change that this is necessary.

Theseus Paradox – The situation is very much analogous the “Ship of Theseus”. According to Plutarch, after Theseus (i.e., the slayer of the Minotaur) returned to Athens from Crete, his ship became a monument to commemorate his great deeds. However parts of the ship decayed due to the exposure to the elements and had to be replaced. After several centuries of this, no portion of the original ship remained. This created the question of whether the resulting ship could truly be referred to as the original ship, or had it ceased to be the original ship long before that.

Now imagine if the ship of Theseus had slowly transformed, not into another ship, but into a chariot instead. This is analogous to the morphological changes that have occurred to the kinnari over its history.

Therefore the problems associated with the Theseus Paradox are a constant presence when talking about the kinnari. Basic questions as to what constitutes a kinnari and its antiquity, are at some level open to debate.

With this caveat in mind, let us undertake a discussion of its history, with a particular emphasis to the morphological discontinuities which punctuate this history.

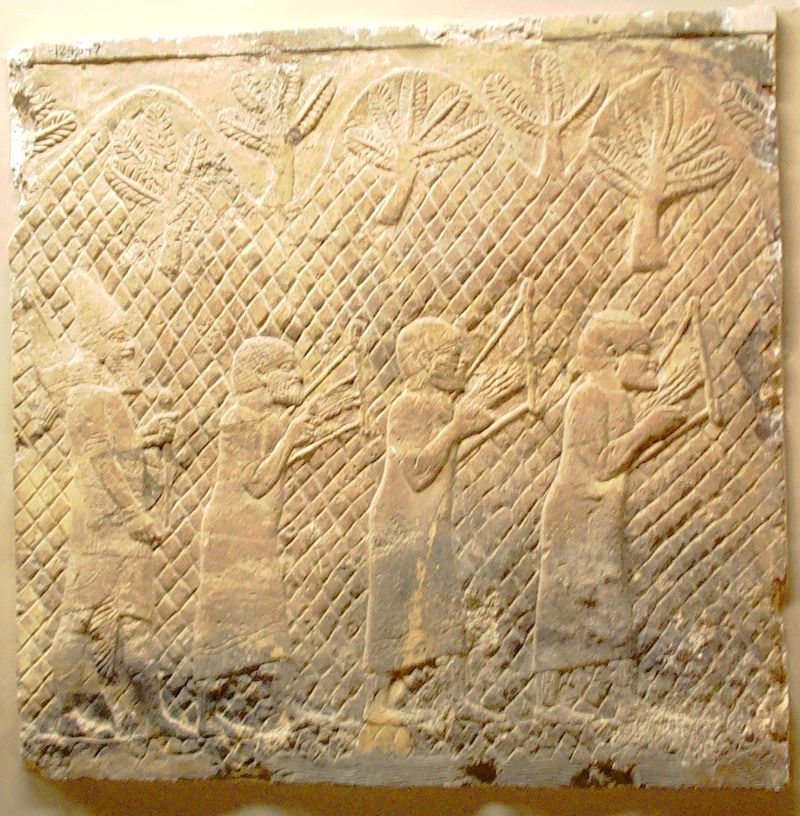

The Biblical Kinnor – The origin of the kinnari is vague; it has been suggested that the earliest mention is to be found in the Old Testament. Here there are frequent allusions to a stringed instrument called the kinnor (Hebrew: כִּנּוֹר). This suggestion is made in C.R. Day’s, The Music and Musical Instruments of Southern India and the Deccan, first published in 1891. This idea has been echoed by other authors over the last hundred years (e.g. Menon 1995).

The exact structure of the Biblical kinnor is unknown, but it is commonly believed to be an instrument of the harp or lyre class. The morphological differences between the contemporary kinnari and any type of lyre/harp, would at first appear to make this highly unlikely. However literary evidence in India suggests that the earliest kinnari were indeed of the harp/lyre class. Therefore the connection between the Indian kinnari and the Biblical kinnor may not be as tenuous as it may at first appear.

This is all very interesting, but must be considered mere conjecture. So little is known about either the early kinnari or the Biblical kinnor that we cannot prove, nor disprove this.

Medieval India – We are in a much more secure position when we advance a few centuries and encounter early literary references to the kinnari in Indian literature.

The first instance of a reference to the kinnari in India is in the 5th Century CE. This also corresponds to its first documented structural change. Matang, the sage of the Brihaddeshi, is said to be the first to mention the kinnari. He also refers to the addition of frets (Deva 1977b). The fact that Matang specifically alludes to this structural modification reinforces the idea that previously the Indian kinnari may have been of the harp/lyre class.

The kinnari is mentioned in the Manasollasa. This work, also known as the Abhilashitartha Chintamani, is an early 12th-century Sanskrit text from South India.

The Sangeet Ratnakara of the 13th century contains an extensive discussion of the morphology of the kinnari. This treatise on music was written by the sage Sharangdev. He mentions not just one kinnari, but several versions differentiated by size.

According to this work, the smallest kinnari is called the laghvi or laghu (Ghosh 1988). This is described as being 15 fingers in length (75 centimetres) and five fingers in width (25 centimetres). The strings are made of steel and tightened by means of a tuning pegs on the side of the instrument. It has two gourd resonators, one of which is larger than the other. The kakubh (the piece of wood with the main bridge) is made of shak wood. Shak is a little hard to translate here because in Sanskrit it can be applied to either teak (Tectona grandis), lebbek tree (Albizia lebbeck), or sigru tree (Moringa oleifera)(Apte 1995). Interestingly enough according to Sharangdev, the laghu kinnari does not have a flat bridge attached to the base (patrika)(Ghosh 1988).

Below is a statue of a celestial musician/ dancer from the Chennakeshava temple in Belur. This temple was commissioned by Vishnuvardhana (Settar 1992) in 1117 CE. This statue was put forth by the musicologist B.C. Deva as possibly being that of a laghu kinnari.

The frets (sarika) may be made of a variety of substances. Sharangdev mentions either the ribs of a vulture, or bars made of iron or bronze. As in the case of contemporary Saraswati vinas, they are said to be the length of one’s little finger (Ghosh 1988). These frets are fourteen in number and allow a range of two octaves. Therefore from Sharangdev’s description we may presume that these frets were tuned in some roughly diatonic fashion.

The vrihat (brhat) kinnari is substantially different; it is the large version. It is longer than the laghu (laghvi) vina by 5 fingers, therefore it should be about 1 metre in total length. It is also said to be wider by about 1 finger (i.e., 5 cm wider for a total width of about 30cm). More importantly, the vrhat (brhat) kinnari has three gourds instead of two. According to Sharangdev, the strings are made from cow’s intestines (snayu)(Ghosh 1988).

The madhyama kinnari is considered to be the mid-sized version. There seems to be some disagreement among different authors as to its size.

The Sangeet Ratnakara gives us a lot information concerning the morphology of kinnari vina in the 13th century. It is clear that the three gourd resonator form, which today is the defining characteristic of the kinnari did not have the same significance. It was definitely present in the form of the vrhat (brhati) kinnari. But the presence of the two gourd laghu kinnari is evidence that the three resonator form had not yet risen to be the defining factor.

It is also worth noting that according to some authors that there were some forms of these kinnaris which were appropriate for classical music and some that were appropriate for folk (desi) music.(Deva 1977b).

Observation – There is something curious about the history of the three-resonator kinnari. Although we have clear literary references to them during the medieval period, they appear to be absent in the iconography from this period. There are ample examples of vinas that have zero, one, or two resonators; but images of three resonator vinas are virtually absent.

There is a complex system of semiotics behind the iconography of temple art in India. It is quite likely that three-resonator vinas simply did not convey the impression or message that the builders of temples wanted to convey. Even today, class associations with various instruments have a tremendous influence upon the way that particular instruments will be shown in film, TV, and print.

For whatever reasons, disconnects between temple iconography and literary references have been noted by other scholars (e.g., Deva 1977).

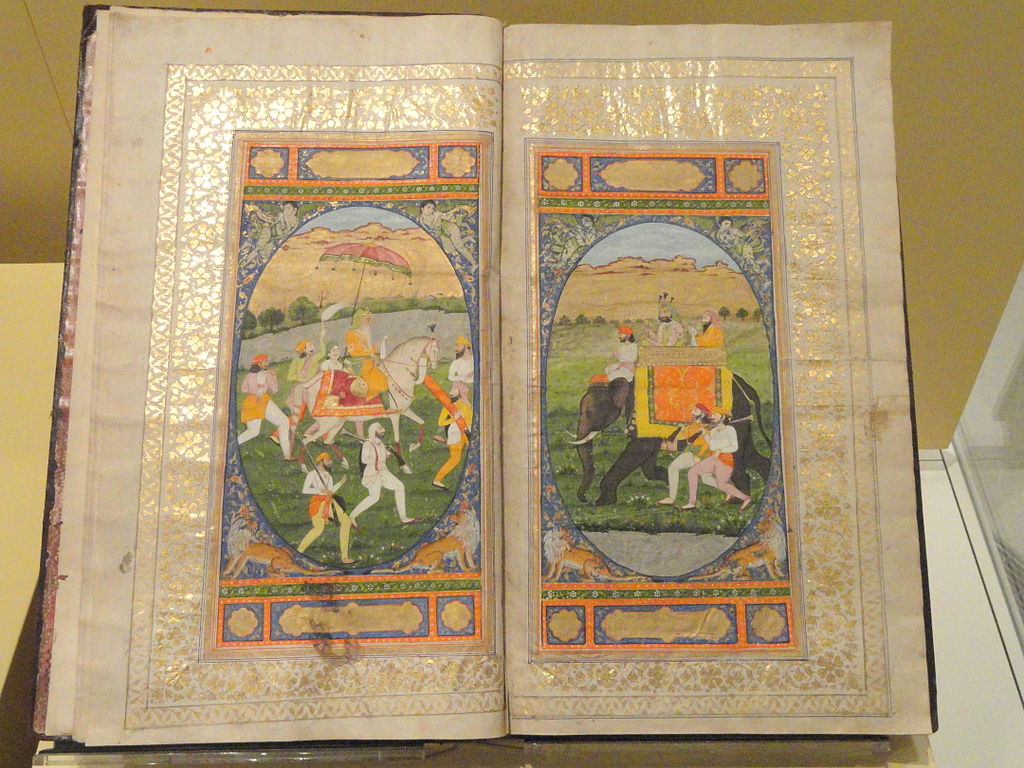

Moghul Period – The three-gourd version of the kinnari appears to have crystallised sometime before the 16th century. This is evidenced by its mention in the Ain-i Akbari. This literary work is an encyclopaedia of the administration of the emperor Akbar, who ruled over northern India from 1556 to 1605. The Ain-i Akbari goes into tremendous detail as to daily life and the administration of his realm. The reference to the kinnari mentions that it resembles the vina (i.e., rudra vina), but that it has a longer finger board, three gourds, and two wires.

Although the reference to the kinnari in the Ain-i Akbari is very brief, it gives us a lot to consider. It is very specific about having three gourds and two strings, both are consistent with modern concepts of the morphology of the instrument. Curiously the kinnari of the Ain-i Akbari has a longer fingerboard than the vina, while contemporary kinnaris are substantially smaller.

The 16th century reference to kinnari in the Ain-i Akbari is not a singular occurrence. It is also mentioned by Ratnakaravarani in his 16th century masterpiece Bharatesa Vaibhava.

Colonial Period – The Colonial Period gives us a different perspective on the kinnari. It is recent enough that a few instruments survive and may be found in museums around the world.

The picture of the kinnari that emerges during period is that of an instrument in decline. It does not appear that the kinnari, at least the three-resonator version, was ever very popular. But from this minor position it started to decline further. Within the classical tradition, other instruments such as the rudra vina, sursringar, sitar, and rabab displaced the kinnari from whatever position it may have occupied. More and more the kinnari became relegated to folk music.

It was not just in the area of musical genre where the kinnari was being marginalise, for its geographical distribution shrank as well. It started to be more associated with the folk music of South India. This set into motion a vicious cycle were the instrument lost its prestige, which then marginalised the instrument to folk musicians, this in turn further depressed its prestige, etc.

There is no mention of the kinnari in S.M. Tagore’s Catalogue of Musical Instruments and Works etc. Forwarded for Presentation to the Royal College Of Music, London (1884). This is very significant when one considers the encyclopaedic nature of the collection.

This narrative of marginalisation is presented by both contemporaneous authors (e.g., Day) and modern Indian musicologists.

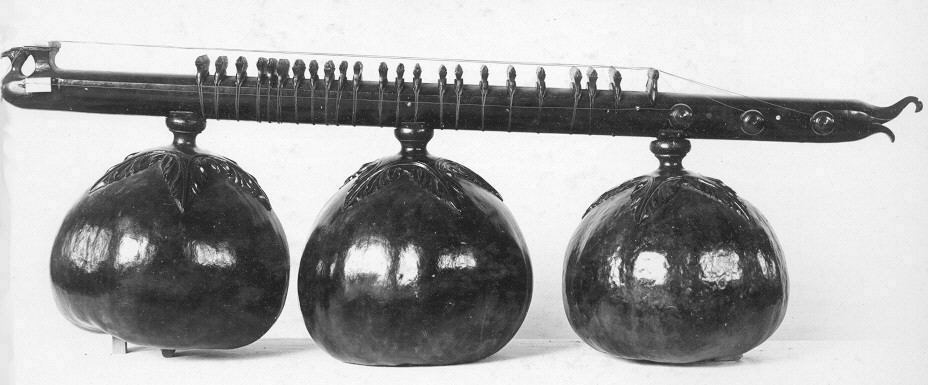

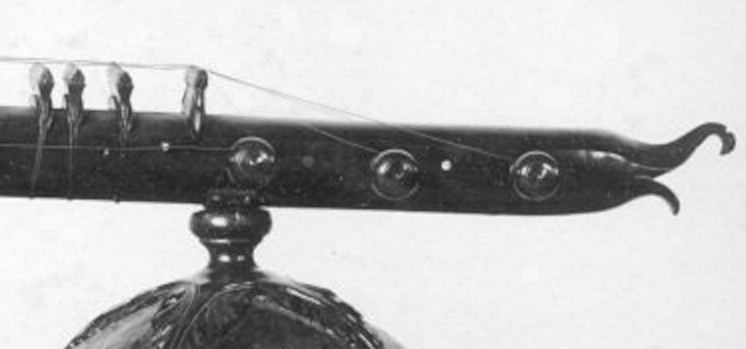

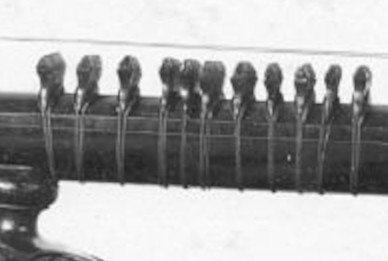

Morphology of Surviving Instruments from the Colonial Period – The morphology of the kinnari is much clearer during the colonial period because we have surviving examples. This allows us to view their structure unfiltered by the vagaries of second or third hand information or the imagination of artists and sculptors.

Stringed instruments are notoriously fragile. Folk instruments are even more so, because they tend to be made from materials that professional musical instrument builders would not even consider using. Nevertheless, there are a small number of kinnaris ensconced in museums around the world.

One of the oldest surviving examples of a kinnari is in the Musée De La Musique, in Paris. This particular item has been dated to the end of the 17th century (Durier, et al. 2019). It is in fairly bad condition, but still shows a familiar structure.

A better maintained version is to be found in the Egmore Museum in Chennai. This particular item is of unknown age; but the majority of the items in the museum were acquired in 1903 (Shekar 2018).

It has previously been mentioned that the kinnari became marginalised and consigned to folk music. But there is a wrinkle in this narrative. A very notable kinnari is to be found in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The museum dates this instrument from 1889.

At first glance there does not seem to be any aspect of the New York example’s morphology that is noteworthy. But on closer examination there are structural elements which are very significant, and are inconsistent with the “folk music” narrative that we just conveyed.

Overall this instrument has many elements which today we find in the more professional rudra vinas. The main shaft does not appear to be made of bamboo; this is evidenced by the lack of nodes. Instead it seems to be made of some type of wood. It also has substantially more than two strings. The frets are not attached by wax but are instead tied on. The number and spacing of the frets, though obviously shifted from decades of neglect, indicate a chromatic arrangement. Furthermore there are clear signs of separate bridges, presumably of camel bone, attached at the end. All in all, this is the work of a professional instrument builder, and not a crude self-made instrument that is typical of the work of an Indian folk musician.

The presence of these elements show a kinnari which was made to play classical music. If we presume that the museum’s dating of the item is correct, then it indicates that someone was playing the kinnari in classical music as late as the 19th century.

So how does this effect our narrative of the later history of the kinnari? This is really hard to tell. It may just be a singular item, perhaps the musical whim of a particular musician. But there is the distinct possibility that this example has a greater significance. We know from literary references that the kinnari was used in both classical and folk music in the 13th century (Deva 1977b). It is entirely plausible that a dual role of existing in both a classical as well as a folk form continued into the 19th century. Unfortunately we do not have sufficient information to answer this question.

Post Independence – Traditional and classical arts in India were inextricably linked with the a sense of national identity, and by extension to the freedom struggle and India ‘s independence. This brings up the question as to what position the kinnari had in this regard.

The concept of “India” and “Indian” have always been problematical. Political stability was predicated upon people first identifying as being “Indian” above their regional and caste identifications. The intelligentsia of the independence movement realised that if this did not occur, it would doom the fledgling India to failure.

The failure of the Uprising of 1857 was to a large part a result of a lack of any cohesive concept of what India (i.e., Azad-i-Hind) should be. Initially the participants in the uprising were militarily very successful. But there was no clear idea of what the post-military political structure should be. The participants sat around and did nothing while the Crown assembled a large body of troops. They paid dearly for their lack of planning and vision in the brutal retaliation that followed.

This failure made it very clear to the next generation of freedom fighters that a sense of national identity had to be established. The leaders felt that an independent India should be based upon three pillars: Hindi, socialism, and secularism. But things did not quite work out as they had hoped. The imposition of Hindi met with strong resistance in non-Hindi speaking areas. Socialism and secularism were laudable goals, but proved too lofty for the common man.

Traditional arts proved to be a useful tool for the establishment of a sense of national identity. In this regard the government enacted many measures. Some of these measures include the creation of the Sangeet Natak Akademi in 1952, the creation / nationalisation of All India Radio (Akashavani), and the creation of Doordarshan (the government run TV stations). All of these entities were entrusted to some degree with the utilisation of traditional Indian arts as a vehicle for national integration.

It is beyond the scope of this webpage to go into the question of how effective these efforts were. However it is for certain that a whole generation of musicians and dancers made a living in a large part due to the patronage of the Indian government.

So where did the kinnari fit into all of this? To a great extent “The bus left without them”. That is to say the kinnari languished in near oblivion. Yet in the last decade there seems to be an increase in interest in the kinnari. Why the sudden resurgence in Interest? It is difficult to know for sure, but we can put forth a hypothesis as to what happened.

A few years after Independence, the Indian government embarked upon a program or “Reorganisation”. In this process state boundaries were redrawn to reflect the linguistic makeup of its peoples. The purpose of this reorganisation was manifold. Its most lofty purpose was to make the fledgling India more democratic. But at a more pragmatic level, it was done to break the traditional identification that people may have had with their erstwhile principalities.

After the states were reorganise according to language, the kinnari tradition found itself in the newly established Andhra Pradesh. One of the few, if not only surviving islands of musicians maintaining this tradition was located in Mehboobnagar (Poshappa 2018) in the Telangana region of the erstwhile Hyderabad state. During the reorganisation, the Kannada and Marathi speaking regions of Hyderabad State were fused with Mysore and Maharashtra respectively. This left the Telugu speaking area of Telangana to be fused with the old Madras Presidency areas of Andhra and Rayalseema.

For various reasons, Andhras assumed a more dominant economic position. They used this dominance to exert a cultural hegemony over Telangana.

The practitioners of the kinnari tradition found it difficult to receive significant patronage in this environment. The kinnari was on the verge of extinction. Its practitioners and supporters had nether the political nor economic wherewithal to assert themselves.

So what changed? The political environment changed.

In the first decade of the 21st century there was a growing movement for the establishment of a separate Telangana state. This movement grew in strength until 2014 when Telangana was made a separate state.

It is only natural that this new state would assert its own cultural identity. In its quest to push all things Telangana, interest in the kinnari increased. Today this instrument is receiving a modicum of interest, and appears to be coming back from the brink of extinction.

Structure

We must confine ourself to recent history when discussing the structure, tuning, and playing of the kinnari. This instrument has been around in some form for many centuries, therefore making all inclusive statements in this regard would be shear folly.

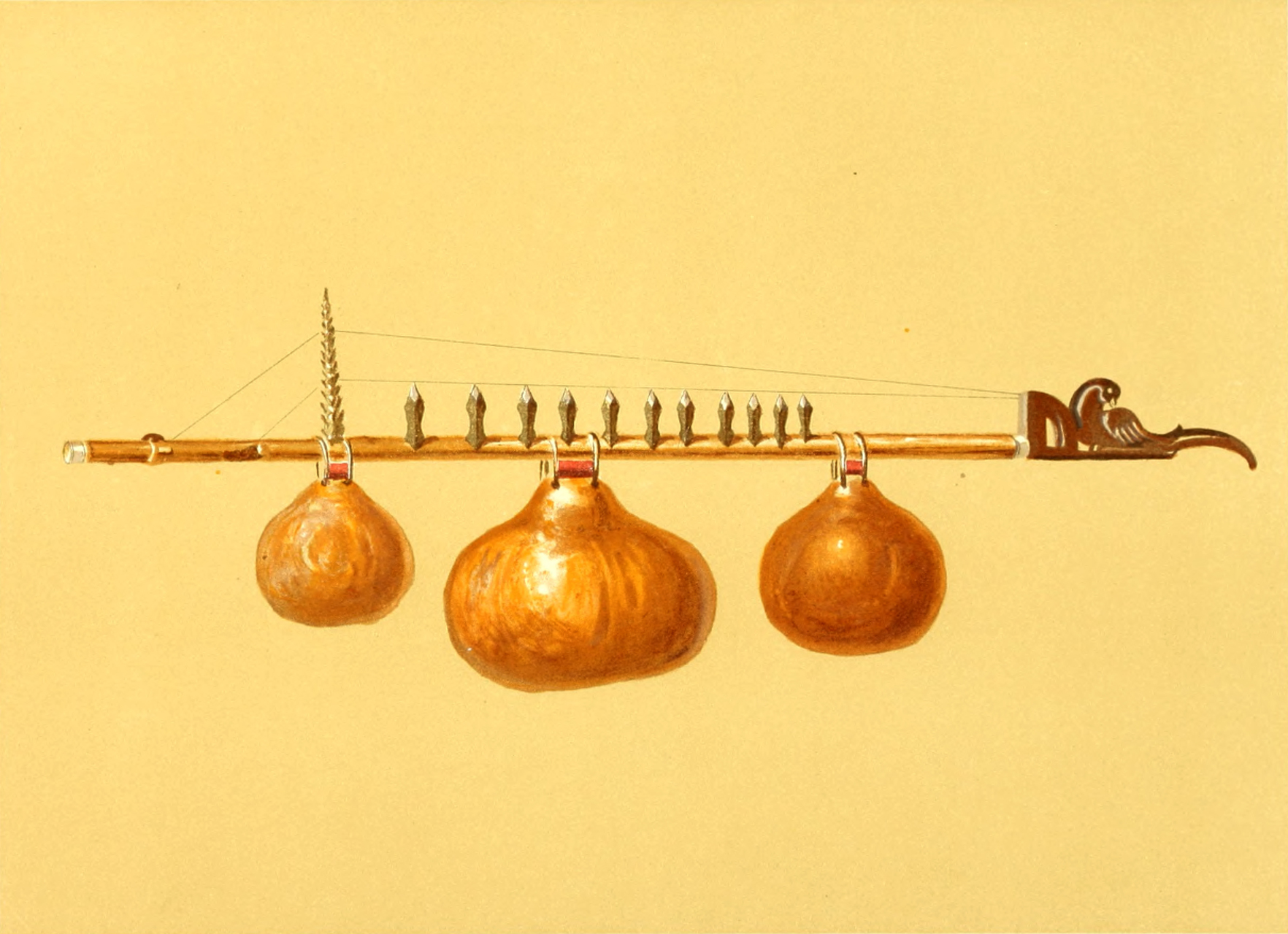

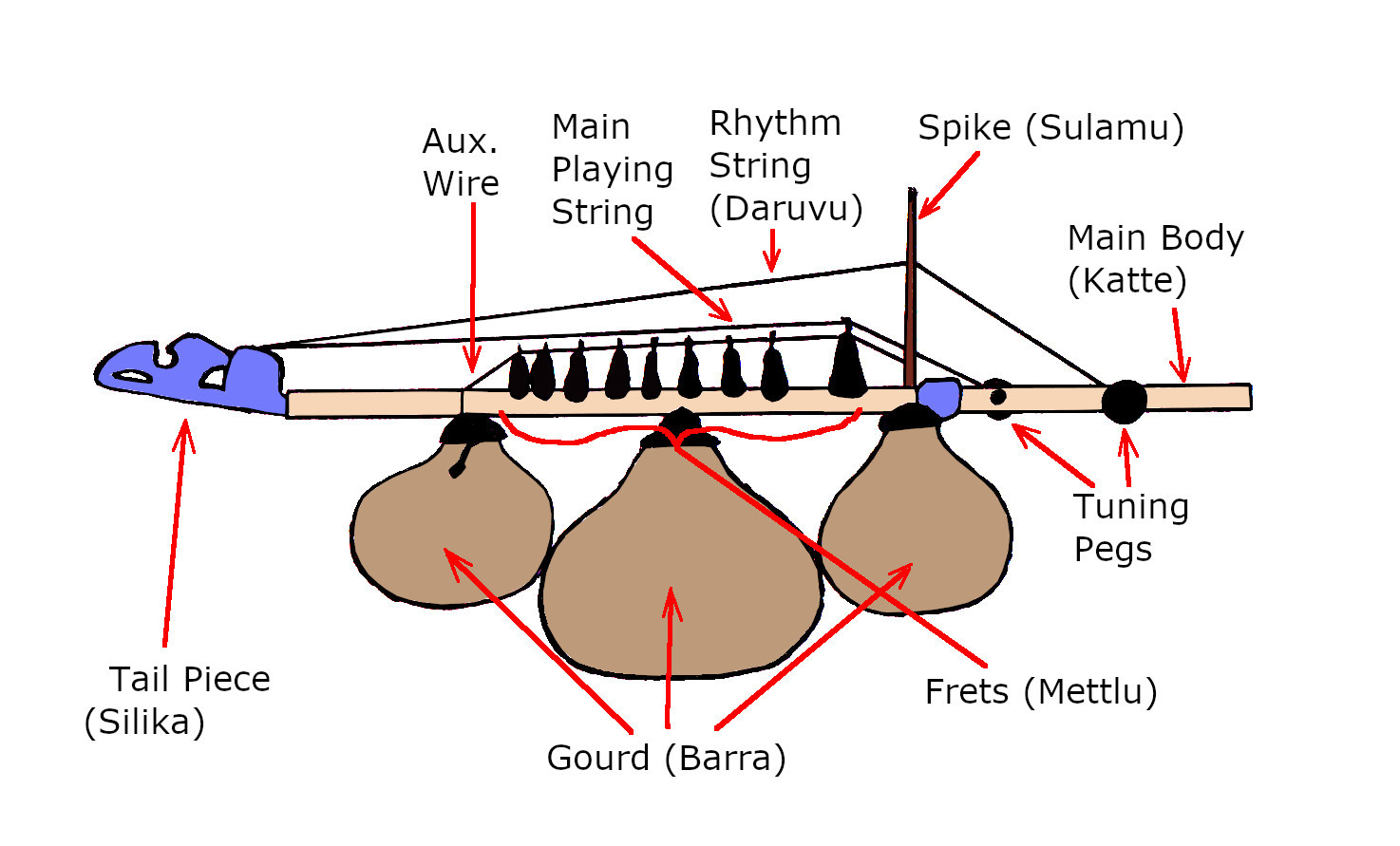

Below is the structure of a kinnari. It is has a central staff (katte). Sometimes this staff is made of bamboo. However bamboo is somewhat problematical because it tends to split with age. Therefore wooden staffs are sometimes employed. To this, three gourds (barra) are attached; these are the resonators. Typical of other resonators in stringed instruments, their function is to provide impedance matching to couple the acoustic energy from the string to the surrounding air.

There is a tail-piece at one end (silika). This tail-piece has strings passing over a bridge. Unlike bridges in most Western instruments, this bridge has a gentle curve rather than a sharp edge. The function of this is to produce a rattling effect and thus generate higher order overtones that would not normally be present.

There are two strings strings made either of steel (Day 1990ay), brass, or bronze (Poshappa, et al. 2018). These two strings have different functions; therefore they proceed down the staff in two very different ways. The main string passes over a series of frets; this is the melody string. There is also a drone string (daruvu). This drone string is held well above the frets by a long spike (sulamu). The drone string is generally tuned to a fourth or fifth below the tonic (Day 1990). These two strings attach at the head by way of two tuning pegs.

There are a series of frets. These frets are made of metal and held into place by a wax like material. The number and arrangement of these frets appears to be variable, but 8-14 seems to be consistent with the various sources. The tuning of these are hard to pin down, but they generally appear to be in some rough diatonic fashion.

There is an auxiliary wire that passes through the frets. The purpose of this wire seems to be primarily structural, but it does effect the sound by producing a distinctive rattling sound. This rattling or buzzing is sometimes enhanced by the addition of beads.

The Music

The music of the kinnari is that of the Telangana folk tradition. It is not possible to deal with this subject here.

Conclusion

The story of the kinnari is a most fascinating one. The mystery concerning its origins, its antiquity, and travails as it attempts to remain viable in today’s world make a gripping study. Although we cannot predict the future, it appears that this instrument has successfully stepped back from the very brink of extinction.

Selected Video

Works Cited

Apte, Vaman Shivram

1995 The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

Abu l-Fazl Allami (a.k.a. Abū al-Faz̤l ibn Mubārak)

Circa 1590 Ain-i Akbari. Translated by H. Blockmann. Delh: 1989. Reprinted by New Taj Office.

British Museum

Undated Photo File:AssyrianPrisonersLyresBritishMuseum.JPG. British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Downloaded Feb 4, 2022.

Cunningham, Alexander

1879 The Stupa of Bharhut: A Buddhist Monument Ornamented with Numerous Sculptures illustrative of Buddhist Legend and History in the Third Century BC. London: W.H. Allen and Co.

Daderot

2011 File:Ain-i-Akbari (The Chronicles of Emperor Akbar), Lahore, Pakistan, c. 1822 – Royal Ontario Museum – DSC09640.JPG. From Wikimedia Commons. Downloaded Feb. 6, 2022.

Day, C.R.

1990 The Music and Musical Instruments of Southern India and the Deccan. (first published in 1891). Delhi: Low Price Publications.

Deva, B.Chaitanya.

1977a “The Development of Chordophones in India”. Journal of the Sangeet Natak Akademi. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi. from http://dspace.nvli.in/handle/123456789/2932 .

1977b Musical Instruments: India – The Land and the People. New Delhi.National Book Trust, India.

1989 Musical Instruments in Sculpture in Karnataka. Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study.

Durier, M., Bruguière, P., Hatté, C., Vaiedelich, S., Gauthier, C., Thil, F., & Tisnérat-Laborde, N.

2019 “Radiocarbon Dating of Legacy Music Instrument Collections: Example of Traditional Indian Vina from the Musée De La Musique, Paris.” Radiocarbon, 61(5), 1357-1366. doi:10.1017/RDC.2019.71

Germain, Claud

Undated Photo Photograph of Kinnari in the Cite de la Musique: Philharmone de Paris.

Ghosh, Sharmistha Sen

1988 String Instruments of North India (Vol 1&2). Delhi: Eastern Book Linkers.

Gunter, Michael (photographer)

2008 Embekke Temple, Carving of a Kinnari 0557.jpg, Wikimedia Commons.

Le Conte,S, S. Vaiedelich and P. Bruguiere

2008 “Acoustical measurement of Indian musical instruments (vina-s): Towards greater understanding for better conservation.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 123(5), 3380.

Menon, Raghav R.

1995 The Penguin Dictionary of Indian Classical Music. New Delhi, Penguin Books.

Poshappa, Dakkali & G. Vetrivel

2018 Telangana I Traditional Music Instrument I Telugu I Kinnera I Mr.Dakkali Poshappa I IIT Hyderabad (Youtube Video) Downloaded Jan 23rd, 2022.

Saletore, R.N.

1985 “Kinnara”, Encyclopaedia of Indian Culture (Vol. 2 E-K), pp749-750. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Settar, S.

1992 The Hoysala Temples: Vol I. Bangalore: Kala Yatra Publications.

Sharangdev

1978 Sangeet Ratnakar. Translated by R.K Shringy and Prem Lata Sharma. Varanasi: Motilal Banarasidas.

Shekar, Anjana

2018 “Yazh to Panchangi Veenai: Forgotten Musical Instruments Now on Display at Egmore Museum.” The News Minute. https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/yazh-panchangi-veenai-forgotten-musical-instruments-now-display-egmore-museum-76202. Accessed Feb 8, 2022.

Subramanian, Karaikudi S.

1985 “An Introduction to the Vina”, Asian Music. Asian music, 16(2), 7-82.

Tagore, Sourindro. Mohun.

1884 Catalogue of Musical Instruments and etc. Forwarded for Presentation to the Royal College of Music, London. Calcutta:I. C. Bose & Co, Stanhope Press.

Tarlekar G. H.

1969 “Some Musical Instruments of Folk and Tribal Music in Maharashtra.” Folk musical instruments of India exhibition and Seminar – November 1968s, Journal of the Sangeet Natak Akademi. January-Mar 1969. online at http://dspace.nvli.in/handle/123456789/2542

unknown photographer

Undated – released by Metropolitan Museum of Art (NY) as CC0 Public Domain, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Vasu, VR

undated photo. File:Musician playing Kinnari vina, sculpture at Chennakeshava Temple, Belur.jpg. Wikimedia Commons. Downloaded on Feb. 3, 2022 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Musician_playing_Kinnari_vina,_sculpture_at_Chennakeshava_Temple,_Belur.jpg. Photo by VasuVRImage modified by Jacqke, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Thirumalai, Venkatarangan (Photographer)

2018 The Government Museum, Egmore, Chennai (Madras), Tamil Nadu

Weismiller, Peter

no date The Been and Beenkars: An Historical Perspective. Accessed January 30, 2022. https://rudraveena.org/peter_weismiller.html