Description

Pashtu, also transliterated as Pashtoo, is an interesting variation upon Rupak tal. Its characteristics, definition, and even its very existence are the subject of much debate.

I believe that the story of Pashtu goes something like this:

There was a major effort to codify Indian music in the early part of the 20th century. There were numerous reasons for this codification. The most obvious one was that the ancient texts that had been around for some centuries were clearly irrelevant to contemporary practice.

However, the process of codifying the music had political overtones. We must remember that this was a time of rising nationalistic sentiments and the concept of an Independent India (i.e. “Azad-i-Hind) was predicated upon a basic concept of “Indian-ness”. Although this may seem strange today, we must remember that there was not a clear sense of Indian self identity at that time. South Asia in the early 20th century was populated by peoples with drastically different individual cultures who were struggling in their search for commonality.

Indian classical music became a part of this emerging sense of self identity. The works of scholars and musicians such as V.D. Paluskar and V.N. Bhatkhande were important in creating, codifying, and spreading “Indian” music.

The desire to unify theses disparate regional and communal cultures of India were reflected in the desire to codify the disparate interpretations of rags and tals into a single cohesive whole. In most cases these attempts were successful. However, in the case of Pashtu / Rupak tal they failed.

It is not clear why Pashtu failed to be amalgamated under the heading of Rupak tal. Perhaps it was because the usage of Pashtu was geographically too far from the present boundaries of India; the name “Pashtu” implies the area on the Pakistan / Afghanistan border. Perhaps it was political; it is possible that in the last century that Pashtu had become associated with a song or particular style of Pakistani music. Perhaps the amalgamation failed because of some inherent musical interpretation; remember, many consider Pashto to be consisting entirely of claps while Rupak tal begins with a khali.

Regardless of what the issues were, Pashtu failed to be amalgamated into Rupak tal. This leaves an interesting question. Why do people not talk of this failure in amalgamation?

Amalgamation as a cultural process is not consistent with traditional Hindu world views. Traditional Hindu world views, and by extension Indian political correctness, are strongly biased toward the process of cultural differentiation. For example, it is the Vedas which are considered the fountain-head of ALL culture; therefore, all modern cultures are believed to have been derived from these. In a similar fashion, Sanskrit is considered to be the mother of ALL languages; therefore, all of today’s vernacular languages (i.e. Prakrit), are believed to have been derived by a process of differentiation.

It is this basic bias toward cultural differentiation that blinds most people in India to the twists and turns of cultural amalgamation. I believe that this is why the failure to amalgamate Pashtu into Rupak tal is not full appreciated.

This is all very interesting, but I am sure that most readers are more interested in the musical characteristics of Pashtu than the cultural issues surrounding its creation.

The musical characteristics of Pashtu are simple. It is usually considered to be three vibhags of three, two, and two matras. All three vibhags are clapped and there is no khali. There are some who consider the structure to be wave, clap, clap; this however does not seem to be the most common view.

Clapping/ Waving Arrangement

clap, 2, 3, clap, 2, clap, 2

Number of Beats

7

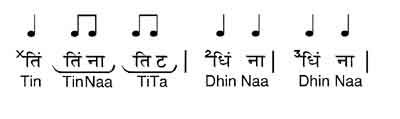

Theka

Popular Songs

Film Songs in Rupak/Pashtu Tal

| This book is available around the world |

|---|

Check your local Amazon. More Info.

|