In Bangladesh

The folk theatre of Bangladesh has an ancient past. However, the continued viability of this tradition is a perennial question. Folk culture in the rural areas, has long been under pressure form the urban culture. Just as folk-crafts have found it difficult to compete with mass produced goods, so too, folk music and theatre must compete with radio, TV, and the cinema. Under the pressure of the larger urban culture, many elements of folk culture have disappeared or been pushed into oblivion. This page will deal with our efforts to revive the traditional kushan theatre of Bangladesh.

Kushan Theatre

The kushan is a form of folk theatre that was once found in many parts of West Bengal and the former greater Rangpur district of Bangladesh. However today, it is extremely rare. Our efforts at reviving this artform have been centred around the Dhorla river basin area of northern Bangladesh. The kushan (sometimes transliterated as kusan), is a dramatic presentation which involves, singing, recitation of dialogue, acting, dancing, and musical accompaniment.

The themes of the kushan theatre are essentially religious in nature and revolve around portions of the Ramayan. In particular they tend to revolve around Ram’s sons Kush and Lob (i.e., Lav).

The etymology of the term “kushan” is unclear. There appear to be two stories concerning the origin of the term; but both of these deserve considerable scepticism.

According to some, it seems that one day Sheeta’s (i.e. Sita) son Lob (i.e., Lav) was missing. Sheeta was in great distress and Balmeeki Muni (i.e. Valmiki) heard of her problems. Sheeta told Balmeeki that she did not know how to tell Sree Raam Chandro (i.e., Sri Ram Chandra) that their son was missing. When Balmeeki heard of Sheeta’s dilemma, he told her to “bring some straw” (Kush = “hay” or “straw”, “aan”= “bring”). When Balmeeki obtained the straw, he fashioned it into the form resembling the missing son Lob, and infused it with life. After some time, the missing son Lob returned, and from that day forward Sheeta had two sons, Lob and Kush. According to this etymology, “Kushan” means “bring straw”.

There is different story concerning the origin of the term. According to other people the word “kushan” means “To wipe away evil” (“ku”= evil, “shan”= “to clean by wiping”). This is supposedly derived from the concept of destroying injustice, which is a consistent theme of the kushan theatre.

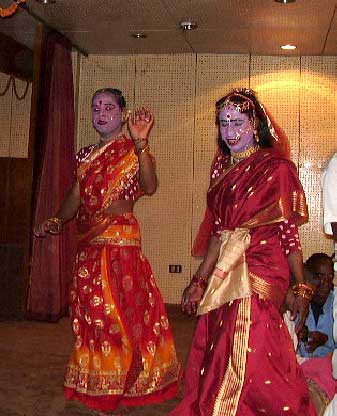

There is a distinctive hierarchy of performers in the kushan theatre. There is a main performer who is also the leader of the group; he is known as the “geedal” or “mool”. The geedal gives the narration in Bengali; this is the official language of both Bangladesh and the North East Indian state of West Bengal. Secondary to the geedal is the dohar, daaree, or doaree. This secondary narrator gives almost the same narration, but instead of a more standard Bengali (Bangla Bhasha), he translates it into a local vernacular dialect of Rangpuri or Rajbongshi. After these come the supporting musicians, and a very few singer-cum-actors. The supporting musicians are known as the “baiin”. The baiin members are named according to their instrument; therfore “banshia” is the banshi (i.e., bansuri) player; Khuli is the khol player; Juridar are the mondira or khafi players (i.e., manjira); and the behala-master is the violin player. there is a slightly different nomenclature for the players of Western instruments; for these, the term “master” is appended to their instrument name. Therefore one finds designations such as, harmonium-master; clarinet-master; etc. The supporting singer-cum-actors are known as “paiil”. Of particular interest among the paiil are the chokra. These are four to six young boys who dress up in women’s clothing and play the female parts of the drama. As is typical of much of South Asia, women performers are not used.

Female Roles Played by the Young Boys (chokra)

Music In The Kushan Theatre

Music and dance are integral to the kushan theatre. However, unlike much of the other theatre of South Asia, dance plays a relatively minor role. Much of the narration is presented in the form of the song. Perhaps the greatest demands are placed upon the main performer (i.e., the geedal), who must sing, provide narration, and play the traditional stringed instrument known as bana.

The songs play an important part in the performance of the kushan. These songs are classified as nachari, dhooya, poyaar, and khosha. Of these, the nachari gives dialogue and naration; the dhooya are popular folk songs), the poyaar are the musical themes of the performance, while the khosha are comical riddles.

Instrumental music is also very important to the kushan theatre. Obviously the major purpose is to provide musical support for the singers and to provide a background for the dance performance. However in the case of the main performer (geedal), the bana actually helps define his position within the performance.

There are a number of instruments which may be used in the kushan. Aside from the bana, there is a bowed instrument known as as sharinda (i.e. saringda). Over the years, this has come to be replaced with the violin or the harmonium; however the use of these Western instruments is not traditional. Arbanshi (i.e., bansuri or bamboo flute) is also commonly employed. There are also a number of percussion instruments used as well; principal among these are the akhrai (e.g., dholak), khol, mondira (i.e., manjira), and khapi (larger manjira).

Typical Format

The kushan performance has a typical structure. It is:

- Bondona (i.e.,Vandana)(adoring/invocation/veneration) – The bondana is what is known in India as a “vandana”. It is a prayer in the form of a song. Such bondonas may be in praise of gods, saints, or gurus (either spiritual or artistic). Typical examples may be Debi Shoroshshoti Bondona (i.e., Saraswati Devi Vandana), Debi Monosha Bondona (i.e. Manisha Devi Vandana)(in folk-theatre Poddopuran only), Dikbondona (Invocation of the blessings of the cardinal directions, east, south, west, and north), Guru Bondona, etc. Each bondona is usually four to five minutes long. Everyone in the group participates in this; but there is no dance with bondona.

- Nachari – This is a type song or a number of songs, whose lyrics describe the forthcoming pala (play). These are dialogues with acting in front of the audience. All the group members participate in this, with a full accompaniment of dance, music, etc. It lasts about five to six minutes. The musical structure is as of vaoaiya which is a very common folksong in this area.

- Palarkotha (dialogues and naration) – These are a few lines of the dialogue which are delivered by the geedal in somewhat standard Bengali; the dohar quickly repeats/and elaborates in the local dialect. In this case it was Rangpuri or Rajbongshi. This is necessary because the locals do not understand standard Bengali very well. This continues for about 10-12 minutes. There is also acting with this. At times, one or two members of the paiil join in for dialogue and acting. There is no dance accompaniment, but there is music.

- Poyaar – The poyaar is generally three to four lines, but sometimes as many as eight lines, of a popular folk song vaoaiya. The themes of which fit with the interludes of the preceding dialogue. It lasts about 10-12 minutes. All the members of the group participate. There is also dance and musical accompaniment. Generally the chokra do not sing because they are busy dancing. These folk dances demand strength in the knees as chokras (i.e, young boy dancers) are required to rise vigourously on the “shom” (i.e., sam or first beat of the cycle). At times three or four subsequent risings are required when a “tehai” (i.e., tihai or a triadic rhythmic device) is given with the khol (i.e., folk drum).

The gach poyaar is particularly interesting; It may be thought of as a theme. These are fundamental poyaars made at the time script is first created. “gach” in Bengali means “tree”, but in this context it means “original” or “fundamental”.

One should note that the term poyaar in the context of folk theatre does not mean the same as it does in mainstream literary circles. Typically a poyaar is Bengali measure of verse consisting of two lines, each of which is 14 syllables. However the poyaar in the folk theatre of Dhorla River basin, area does not adhere to this structure.

- Nachari – See #2

- Palarkotha – see #3

- Poyaar/dhooya/ Khosha – At this point there will be poyaar, dhooya, and khosha. The poyaar has already been discussed; however the terms “dhooya” and “khosha” deserve some discussion.

Dhooya – These are also a few lines of any very popular vaoaiya/chotka, but not related to the theme of the play. All the members participate in this. The music of this is generally in a 3/4 time signature (“druto” or fast dadra tal).

Khosha – This is a short comedy drama, which need not directly related to the story of the play. It generally lasts for 20-30 minutes. It is performed by geedal, dohar, and one or two of the paiil. There is no dancing in this, but there is musical accompaniment. Very often this comedy takes the form of a riddle. Khosha was extremely important in the old days when there used to be competitions (norok). It is considered to be the most interesting and most attractive portion of the performance.

- Nachari – see #2

- Palakotha – see #3

- Ending – In one night a play is performed for 6-7 hours. It is ended by singing a dhooya; however before ending, the geedal lets the audience know that it is finished and invites the audience for future performances.

Revival Efforts

Recently there was a effort to revive the kushan theatre of the Dhorla river basin. The last time it was played in this remote area of Bangladesh was about 27 years back (from 2005 CE) . After such a long hiatus, there were many challenges which needed to be overcome. The challenges at times involved logistics (i.e., power generators, venue, videotaping, etc.). However, these challenges at times were cultural and social in nature.

The first and greatest difficulty would be finding of the main performer (i.e., the geedal). It was fairly clear that if a competent geedal could be found, then from there it would be possible to either find or train the rest of the performers. Only three performers were found in the area; of these only two were acceptable. One was Mohesh Chondro Bormon and the other was Shadhu Robindronath Roy.

One acceptable kushan leader (geedal) was Mohesh Chondro Bormon. Mr. Bormon was a resident of Foolkhar Chakla; he was about 90 years old.

Mohesh Chondo Bormon and Party

Another acceptable kushan leader (geedal) was was Shadhu Robindronath Roy. He was a resident of Khamargobindogram; he was about 76 years of age. Although Mr. Roy proved to be very knowledgeable about kushan and the great geedals of the past, things did not always proceed in a smooth manner. At one point, he claimed that he was giving up worldly pursuits and living in the temple; therefore it would not be possible for him to perform the kushan.

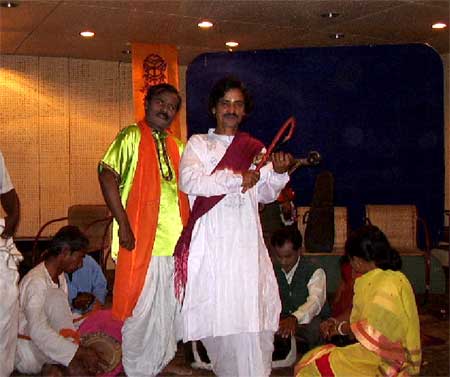

Shadhu Robindronath

We were also able to locate another geedal named Kripa Shindhu Roy in Rotigram, but unfortunately he did not work out. One of the reasons for his not being able to do it was that he did not possess bana; since this is a requirement for the geedal, this was a problem. Furthermore, he said that after so many years, he could not remember the script that we were wishing to perform. Still, he is a performer of some repute in many other ways.

With two qualified geedals, it was then possible to create two functioning kushan theatre groups. However half a century ago an area such as the Dhorla River basin might have had a larger number of groups. This allowed them to have competitions between them. In the old days, such competitions were a matter of great interest to the people. Such competitions were called norok and would go on for several nights.

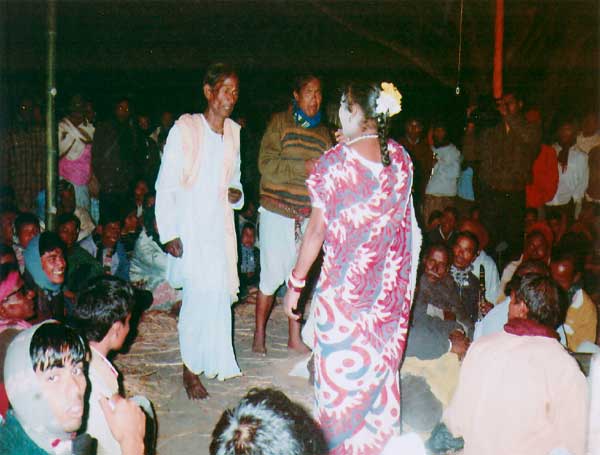

The Performances

First kushan was revived and presented on the night of December 12, 2006. This was the first time that the kushan had been presented in this area in nearly three decades. The name of the play was “Boilabodh”. The geedal was Shadhu Robindronath Roy and dohar (i.e., translator) was Nirmol Chondro Roy. The revival was fully supported by this researcher Wing Commander Mir Ali Akhtar (Retd.). The place was Khamargobindogram, Goddess Kali’s Mondir Yard. In spite of this being a rainy winter night, turnout was good and the performance was well received. Power for this performance was provided by a small portable generator.

Kushan Performance in Village

The revival of the kushan created a good deal of publicity. As a result of several newspaper articles, the Bangla Academy, and Shilpokola Academy of Bangladesh started to take interest in this revival. With their support, the kushan was able to be performed in several venues around the capital during Febrary 2007. According to many, this was the first time in centuries that the kushan has been performed in Dacca.

Kushan Performance in Dacca

Conclusion

The continued viability of the kushan theatre, is a matter which is still not clear. However the interest generated by this recent revival is certainly a positive sign. It can only be hoped that the renewed interest will be reflected in renewed patronage and an increase in younger artist willing to embrace this artform.