| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the first volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Fundamentals of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Introduction

Tal, (variously transliterated as “tala”, “taal” or “taala”) is the Indian system of rhythm. It has been argued that rhythm is fundamental to the creation of any musical system. Certainly from a historical standpoint, rhythm existed many centuries before the word rag was ever used. Given this historical preeminence, it is not surprising that rhythm occupies an important position in Indian music.

There are things that will be covered in this page and things that will not. We will discuss the concept of tal primarily from the North Indian perspective. We will not list the various North Indian tals and their thekas, because this is covered elsewhere in this site. Similarly, we will not discus the bols of tabla and their techniques; this too is covered elswhere. We will however look very closely at the theoretical aspects of the North Indian approach to rhythm.

The word tal literally means “clap”. Today, the tabla has replaced the clap in the performance, but the term still reflects the origin. The basic topics we will cover are:

- The etymology of the term “tal” (tala).

- The tali is the pattern of clapping. Each tal is characterised by a particular pattern and number of claps.

- The khali is the wave of the hands. These have a characteristic relationship to the claps.

- The vibhag is the measure. Each clap or wave specifies a particular section or measure. These measures may be of any number of beats, yet most commonly two, three, four, or five beats are used.

- The matra is the beat. It may be subdivided if required.

- The avartan is the basic cycle.

- There must be a system of timekeeping. At first this would appear to be a mere practical detail; however a change in the timekeeping that occurred within the last few centuries has profoundly affected the way in which North Indian musicians conceptualise the tal.

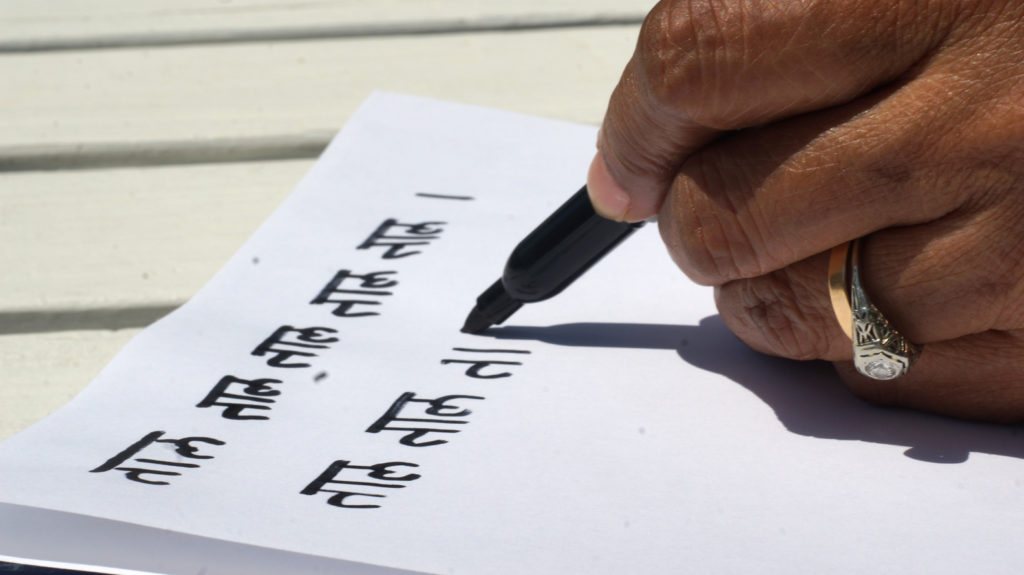

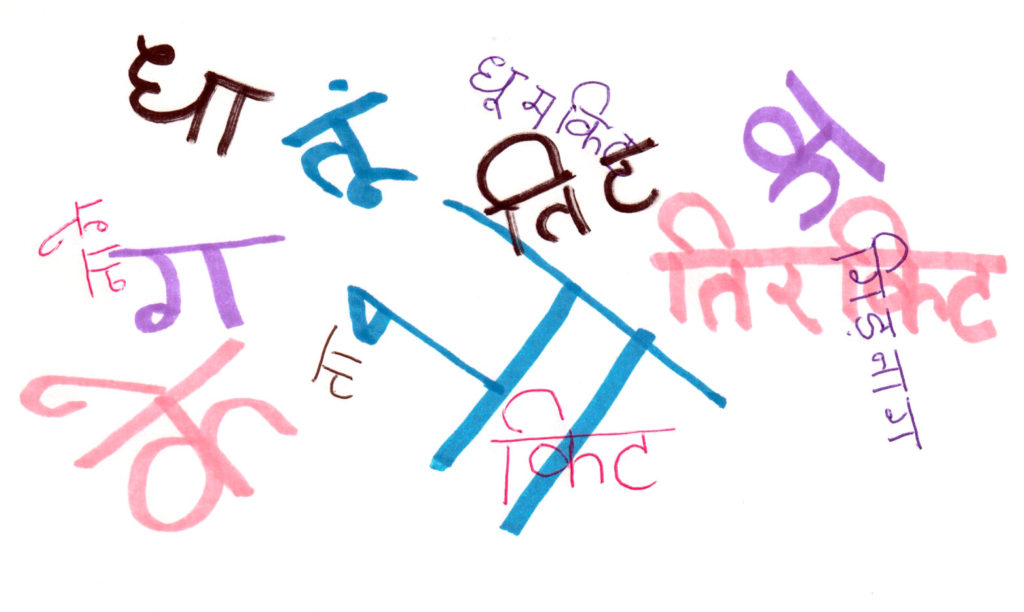

- The bol is the mnemonic system where each stroke of the drum has a syllable attached to it. It is common to consider the bol to be synonymous to the stroke itself.

- The theka is a conventionally established pattern of bols and vibhag which define the tal.

- The lay (laya) is the tempo. The tempo may be either slow (vilambit), medium (madhya), or fast (drut). Additionally ultra-slow may be referred to as ati-vilambit or ultra-fast may be referred to as ati-drut.

- There is a relationship between what is being played and the underlying tempo. This is often referred to as “layakari“.

- The sam is the beginning of the cycle. The first beat of any cycle is usually stressed.

- There are a number of archaic aspects of the tal. This manifests itself in the “Dasa Prana”.

Etymology (The Origin of the Word “Tal”)

It is appropriate for us to look at the origin of the word tal. Please note that for this page we will be using the transliteration “tala” to refer to a more Sanskritic usage while we will be using “tal” to refer to contemporary Hindi. There is a slight difference in pronunciation, but it really isn’t significant.

The Practical Sanskrit – English Dictionary (Apte 1987) gives the primary definition of “tala(h)“, as a “surface”. This is further extended to a variety of usages which include the “palm of the hand”, “a slap of the hand”, and “clapping of the hands”.

It is not too great a leap to go from the “clapping of the hands” to a more general definition of “rhythm”. (This will be discussed more in the section on “tali“.) There seems to be no indication that “tala” is a Sanskrit neologism, so we may surmise that it is a word of extremely great antiquity.

Bogus- Etymology – There is a bogus etymology of the word “tala“which is circulating. But what do we mean by “bogus etymology”?

Studying any aspect of Indian culture unearths many etymologies that simply are not true. Probably the most famous is the widespread belief that “guru” is derived from “gu” which means “darkness” and “ru” which means to dispel; hence a guru is the “dispeller of darkness”. The actual etymology is far less poetic, for it is derived from the Proto-Indo-European “gur” which means “weighty”, thus implying “authority”.

There is a fairly common bogus etymology concerning the origin of the word “tala” (tal). The word is said to be a combination of “ta” and “la.” “Ta” being derived from Tandava which represents the masculine principle embodied in Shiva.”La” on the other hand being derived from Lasya which represents Parvati or the feminine aspect of Shiva. Therefore ta-la, or “tala,” is emblematic of the union of the universal masculine and feminine principles (Mani undated).

This as well as other bogus etymologies, speak volumes as to traditional Hindu sentimentalities. But they obfuscate the intellectual environment and make serious studies difficult.

Tali (The Clapping of Hands)

The clap of the hands is an important part of both the theory and practise of North Indian music. It has a hoary past. An elaborate system of clapping and hand movements is mentioned in the Natya Shastra (circa 200 BCE) where it is part of the system of timekeeping known as “kriya”.

The clap of the hands is very important for the conceptualisation of Indian rhythms. North Indian musicians use the claps to designate the measures (vibhag). The most important measure is the beginning of the cycle. The first beat of which is called the “sam”.

The clapping of hands is also of great practical importance. It is a convenient means for the singers and other musicians to communicate with the tabla player (tabalji) without having to break the performance.

The clapping must not be taken only into itself because it exists along with its compliment the wave. This wave or “khali” is also important in designating the measures.

Khali (The Wave of the Hands)

The word “khali” literally means “empty”. However, in the field of north Indian music, it has a special significance. Here the word implies a wave of the hand. This wave of the hand, along with its counterpart the clap of the hand, forms the traditional basis for timekeeping in north India.

The wave of the hand is used to designate the first beats of measures which are only moderately stresses. Therefore, one almost never finds the khali applied to strongly stressed beats like the “sam” (the first beat of the cycle)

The khali is especially important in symmetrical metres such as Tintal of 16 beats or Dadra of 6 beats. For such symmetrical tals, the khali is indispensable for correct orientation. For example, if there were no khali, Tintal would be a confusing string of four beat measures, and it would be very difficult to find the beginning of the cycle. Therefore, the khali may be thought of as an index.

| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the second volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Advanced Theory of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Vibhag (Ang) (The Measure)

The vibhag in north Indian music is analogous to the Western concept of the measure or bar. However, in Indian music the cycle (avartan) is much more important than the measure. In the old scriptures the vibhag was often referred to as the “ang”.

The vibhag may be any number of beats; however two, three, or four-beats are the most common. The vibhags may be put together in any fashion; but the arrangement is always fixed by convention. Therefore, Tintal by convention will always be four vibhags of four beats each, Ektal will always be six vibhags of two beats each, etc.

The vibhags must be designated with either a clap or a wave of the hand. This convention makes communication easier. In the rhythmic notation (tal lipi), any vibhag which is khali is designated by a zero at the beginning. Any other symbol is used to designate a clap or tali. Usually a number is used which corresponds to the clapping. Therefore a “3” at the beginning of a vibhag would indicate that it was the third clap in the cycle, a “2” would indicate the second clap, etc. The sam is the most important, and it is designated with a “+”, or an “X”.

Matra (The Beat)

The matra is the beat in Indian music. Along with the vibhag (measure) and the avartan (cycle), it is one of the three levels of structure for Indian rhythm (tal).

The beats may have a different significance depending on where they come in the cycle. Beats that occur at the beginning of any measure (vibhag) are always more significant then the beats which occur midway in a measure. The first beat of the cycle is the most important beat of all. It is called sam.

Indian music does not flow in metronome time; therefore the value of the beats may be stretched or contracted depending on numerous factors. This is easily demonstrated, but surprisingly enough is not acknowledged in traditional theory. One must understand the music thoroughly to know when such liberties are appropriate.

Avartan (The Cycle)

The avartan is the cycle in North Indian Music. It is composed of measures (vibhag) which are in turn composed of beats (matra).

The avartan is comparable to the Western cycle (e.g. a 16-bar blues pattern) but with a few differences. One of the biggest differences is that in Western music the measure is considered inviolate, while in North Indian music the cycle is considered inviolate. That is to say that a Western musician would think nothing of establishing a 16-bar pattern, break the pattern for some artistic reason, and then reestablish it; however the measures would usually be the same. Conversely, Indian musicians typically will mix the measures. For instance Jhaptal is four measures of two-beats, three-beats, two-beats, three-beats respectively; however the overall 10-beat pattern may not be altered.

Avartans may be of any number of beats. The most common numbers are sixteen, fourteen, twelve, ten, eight, seven, or six beats. Most of the music played in Northern India today is in one of these numbers.

Timekeeping

Time-keeping is the act of maintaining the rhythm in a performance. In a Western orchestral situation, the timekeeping is done by the conductor. In a contemporary popular musical performance, the responsibility for timekeeping is shared between the drummer and the bass player. But what is the situation in India?

Historically, timekeeping was done by a musician clapping and waving their hands. This clapping and waving of the hand corresponded to the structure of the beats and measures of the cycle. This is the way that South Indian rhythms are conceptualised today. It is also the way that the old Dhrupads and Dhammars of North Indian music were treated in the past.

But a few hundred years ago there was a change in north Indian music that had profound implication for the theory and practise of the music. The responsibility of timekeeping shifted to the tabla player. This introduced some new requirements for the tabla players.

The most important requirement was the need for some type of standardisation in the playing. This was reflected in the rise of the theka. This standardisation was necessary so that a main musician could feel comfortable sitting down with different tabla players. Even with different tabla players, they could still be fairly sure of what the accompaniment would be like.

Bol (The Syllables)

The mnemonic syllable is known as bol. This is derived from the word “bolna” which means “to speak”. The concept of bol has a number of different characteristics. These relate to the manner in which the bol relates to the technique of the tabla. They also relate to the way that the bol is used to define the tal.

The manner in which the bol relates to the technique of the tabla is perhaps the most important consideration of all. This is described in greater detail under the topic “Basic Strokes and Bols”.

There are a few twists when the bol is used in the accompaniment of the Kathak dance; This is known as padant. These syllables may be a mixture of tabla bols, pakhawaj bols, bols that are peculiar to the Kathak dance, and at times even poetry and words.

Philosophical Implications – The syllables are usually considered to be mere mnemonics which represent the various strokes of the tabla or other percussive instruments; but perhaps this is not really correct. Perhaps it is really the strokes on the drum that represent the syllables. This is because the syllables have been elevated to an abstract level that is at times divorced from the technique used to suggest them.

This may be a hard concept to follow, so let us explain this a little more clearly. Let us take a more familiar example such as the word “door”. The word “door” at first appears to be solidly connected to that familiar household fixture. It would seem that the utterance of this single syllable is there to remind us of this. But when we look further, the word “door” starts to disconnect from the familiar household fixture. It begins to assume a broader significance. Take for example the expressions “doorway to the mind”, or “door to the future”. One would have no problem thinking of countless other examples where “door” is used in a more abstract sense. So now the relationship is no longer clear. Is the word “door” a description of the household fixture, or is the household door a physical metaphor for a larger philosophic concept?

This same ambiguous relationship is seen in the syllables for the Indian drums. Originally, they may have been mere onomatopoeic representations of the strokes. However, multiple ways to execute the syllables have weakened this relationship. Furthermore, the syllables acquired their own syntax and grammar. They are easily manipulated without recourse to their technique. In short, they have assumed an identity all their own.

| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the fourth volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Focus on the Kaidas of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Theka & Prakar (The Supporting Groove)

The word “theka” literally means “support” (Pathak 1976). Originally the theka was nothing more than a “groove” that was laid down for the accompaniment of other musicians. However, in the last few centuries it has emerged as “the” signature for any north Indian tal.

Theka is a conventionally accepted arrangement of common bols. Due to this convention different tabla players can sit down with different main musicians and feel confident that they can perform with a minimal degree of awkwardness.

There is the concept of the prakar which is very closely related to the theka. They are so closely allied that in practise the prakar is considered to be synonymous with theka. The word “prakar” is defined in Bhargava’s Standard Illustrated Dictionary of the Hindi Language, as meaning “method” or “manner” (Pathak 1976). The prakar is nothing more than a different way to play the theka.

It would at first appear that the existence of the prakar would contradict the earlier statement that the theka is a standard approach. It isn’t really. It merely reflects the latitude which is extended to the performer in this regard.

It is a curious fact that in the last few centuries the theka/prakar has replaced the clapping and waving as the means by which North Indian musicians define the tal. This is illustrated with the following examples:

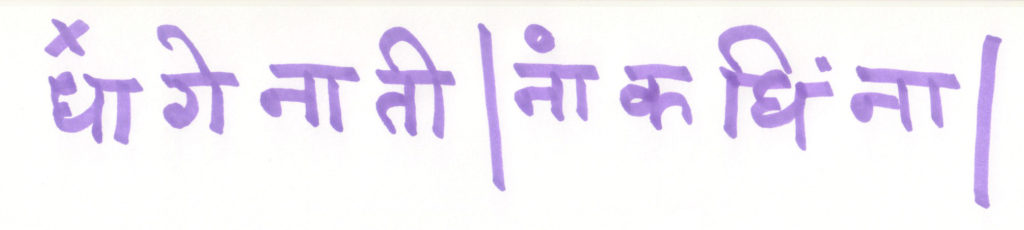

Tintal

XDhaa Dhin Dhin Dhaa | 2Dhaa Dhin Dhin Dhaa | 0Dhaa Tin Tin Naa | 3Naa Dhin Dhin Dhaa |

Tilwada Tal

XDhaa TiRaKiTa Dhin Dhin | 2Dhaa Dhaa Tin Tin | 0Taa TiRaKiTa Dhin Dhin | 3Dhaa Dhaa Dhin Dhin |

Adha Tal

XDhaa – Dhin – | 2Dhaa Dhaa Tin – | 0Taa – Tin – | 3Dhaa Dhaa Dhin – |

These are three distinct tals which share the same abstract structure (i.e., claps, waves, numbers of beats, and measures), but they are considered separate tals ONLY because the bols of their thekas are different. Historically, this has not been the case.

This brings us to the topic of the pakhawaj. The pakhawaj, being a much older instrument than tabla, still tends to conceptualise the tal by means of the clapping and waving, and not by any conventionally accepted theka. However, since the pakhawaj and its associated melodic forms are so very much rarer than the tabla and its associated forms, we may give them considerably less attention.

We may make a few observations about the structure of theka. These are generally the case, but must not be considered to be a rule.

One observation is that there is a tendency for theka to be based upon two symmetrical structures. Let us look at Jhaptal for example:

XDhin Naa | 2Dhin Dhin Naa | 0Tin Naa | 3Dhin Dhin Naa |

In this example the structure Dhin Naa Dhin Dhin Naa is opposed by Tin Naa Dhin Dhin Naa

This symmetry is also illustrated in Dadra tal; it goes like this:

XDhaa Dhin Naa | 0Dhaa Tin Naa |

In this last example the phrase Dhaa Dhin Naa is reflected in the structure Dhaa Tin Naa.

It must be stressed that there are numerous thekas which do not exhibit this symmetrical quality. Rupak is a very common theka which is asymmetrical; it goes like this:

0Tin Tin Naa | 1Dhin Naa | 2Dhin Naa |

There is another observation that we can make about the structure of the theka; there is a tendency for the bols to follow the structure of the vibhag. If we look back at the Jhaptal in the earlier example we see that the 2,3,2,3, clapping arrangement of Jhaptal is reflected in the bols Dhin Naa Dhin Dhin Naa Tin Naa Dhin Dhin Naa. Again, the numerous exceptions show that this is merely a tendency rather than a rule.

Lay (Laya) (Tempo)

Lay is the tempo, or speed of a piece. The Hindi term for tempo is “lay”, and is derived from the Sanskrit term “laya”. It is a very simple concept, but its application is sometimes complicated. We will also discuss the related concept of layakari.

It goes without saying that there have to be some practical limit to usable tempi. One beat every ten minutes would be so slow as to be musically useless. At the other end of the spectrum we can see that 100 beats-per-second would be so fast that it would be perceived as a tone and not as a rhythm.

There is a tendency among many musicians to catagorise the tempo into three categories: vilambit (slow), madhya (middle), and drut (fast) (Patnakar 1977). This is obviously insufficient for the demands of a practising musician. Therefore this sytem is generally expanded into the form shown in the following table:

| ati-ati-drut | 640 beats-per-min |

| ati-drut | 320 beats-per-min |

| drut | 160 beats-per-min |

| madhya | 80 beats-per-min |

| vilambit | 40 beats-per-min |

| ati-vilambit | 20 beats-per-min |

| ati-ati-vilambit | 10 beats-per-min |

The table is an idealised breakdown of lay; however, the real world is considerably more complex. For example the designations of ati drut, ati vilambit, etc. are seldom heard among practising musicians. This tends to stretch the previous table so that there is no longer a 2-1 relationship between the various designations. To make matters even more complex, it has been observed that vocalists use a slower definition of time than instrumentalists (Gottlieb 1977a:41). Furthermore the rhythmic concepts of the light and film musicians run at a higher tempo but show a peculiar compression of scale. Therefore the numbers presented here must be taken as the roughest of an approximation.

The lay or tempo usually changes throughout the performance. These changes in tempo are inextricably linked to the various musical styles. In general we can say that only very short pieces will maintain a fairly steady pace. Most styles will start at one tempo and then increase in speed.

Layakari (The Performance vs. the Underlying Beat)

The relationship between what is being played and the underlying tempo is an important consideration. When one is listening to a classical north Indian performance, the tabla player frequently takes off on a very fast elaboration of the tal. The important thing to note is that in spite of the often blinding speeds of such elaborations, the tal did not necessarily speed up. Therefore the relationship between what is being played and the underlying tempo is very important.

Although this is an important concept, there is no universally accepted term for it. One word which seems to be often invoked is the term “layakari“. Another term which is sometimes used is “kala“; this though is problematic because its usage in this context is divergent from its historical meaning. In the old Sanskrit texts, kaal would be synonymous with lay (Stewart 1974). (The lack of standard terminology is a ubiquitous problem in the study of Indian music.)

Below is a table showing the major relationships:

| English | Hindi / Urdu |

| Single-Time | Ekgun, Barabar, or Thanh |

| 5 Strokes over 4 matras | Kuadi or Savai |

| 6 Strokes over 4 matras | Adi-Lay or Derdh |

| 7 Strokes over 4 matras | Biadi-Lay or Paune dugan |

| Double-Time | Dugan |

| 5 strokes over 2 matras | Mahakuadi |

| 6 Strokes over 2 matras | Mahaadi or Tigun |

| 7 strokes over2 matras | Mahabiadi |

| Quadruple-Time | Chaugun |

| 5 Strokes per matra | Panchgun |

| 6 Strokes per matra | Chehgun |

| 7 Strokes per matra | Satgun |

| 8 Strokes per matra | Aathgun |

| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the first volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Fundamentals of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Sam (The First Beat of the Cycle)

The sam is the first beat of the cycle. The word “sam” literally means to “conjoin” or “come together”. The sam has a special significance in both the performance and theory of North Indian music.

The main function of the sam is to establish a point of resolution. Although improvisations and fixed compositions may begin almost anywhere in the cycle (avartan) they usualy resolve on the sam. (A notable exception is that the start of the main theme is also treated as a point of resolution.)

The sam is also a pivotal point. Typically the tabla player keeps time by playing theka and the main musician is free to improvise. This however would be boring if that was the only thing that happens; therefore it is common to exchange roles. During this, the main musician keeps time by playing the theme (gat or sthai) over and over. This allows the tabla player to take off and improvise. After a period the roles reverse again. The sam is important because it is pivotal to this transition.

The sam is so important that it has its own notational symbol. In the Bhatkhande system of notation, it is noted with cross such as an “X” or an “+”, usually an “X”.

The sam is almost always a clap of the hands (tali). There is only one exception and that is the case of rupak tal. This lone exception designates the sam with a wave of the hands (khali).

Dasa Prana (Archaic Aspects of Tal)

There is a large body of material which was extracted from ancient texts and clumsily grafted upon contemporary musical practise. The most prominent from the standpoint of tal is the “Dasa Prana”.

Many of you will be sitting for your exams and you will have to memorise this stuff. Most of it will not make sense. As far as your life as a practising musician is concerned, it is just irrelevant b.s. You should memorise it, spit it out on the exam, pretend that you know what it means, take your diploma, and forget about it. I promise you that it doesn’t make sense to the examiner either.

Antiquity = Authority – It is a peculiarity of traditional Hindu world views that validity is automatically equated with antiquity. That is, if something is very old it must automatically be vested with authority. In a similar way, if something has great social value (as classical music clearly does,) it automatically must have a great antiquity. This leads to overly complex hermeneutics in unsuccessful attempts to shoehorn contemporary musical practise into irrelevant archaic musical systems.

We do not wish to impugn this particular world view, for the two common alternatives in India also have their follies. For instance, Western teleology has no more value than the traditional Hindu approach. This teleology is implicit in slogans such as “New and Improved”, or “Latest and Greatest”, and is equally prone to failure. In a similar way, the Islamic approach of automatically assigning a different value to things according to whether they came before the age of the prophet Mohamed (p.b.u.h.) or afterwards, is equally fallacious.

| IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN TABLA, THIS BOOK IS FOR YOU |

|---|

This is the second volume of the most complete series on the tabla. Advanced Theory of Tabla It is available around the world. Check your local Amazon for pricing. |

Dasa Prana – Introductory Remarks – Much of the ancient theory behind tal is dominated by the concept of Dasa Prana, or “ten vital breaths” of rhythm. Although most of the individual terms were in existence during the time of the Natya Shastra (circa 200 BCE), the term Dasa Prana is hard to trace back further than the 11th century. (Shepherd 1976). The Dasa Prana is presented below:

- Kaal – The time

- Marg – The pause

- Kriya – The action of Timekeeping

- Ang – The sections

- Graha – The process of starting

- Jati – The classes of rhythmic patterns

- Kala – The Sections

- Lay – The tempo

- Yati – The arrangement

- Prastar – The permutations

We will now proceed with a typical interpretation of the Dasa Prana derived from contemporary sources (e.g., Vinjamuri 1986). It must be stressed that the concept of Dasa Prana is of questionable relevance to contemporary practise. We are presenting it here so the student can get a sense of perspective.

1st Aspect of Dasa Prana (Kaal) – The word kaal literally means “time”. Conceptually, it is an absolute framework for denoting the duration of a beat or musical note.

The Hindi word “kaal” is derived from the Sanskrit “kaala” and has a number of uses and precise meanings. The Concise Sanskrit-English Dictionary (Apte 1987) gives the definitions of “Kaala” as “black,” “time; proper time; god of death; destiny; the planet Saturn; poison and iron.” From the list of meanings, it is clear that there are two root concepts: one being time and the other being the concept of blackness. Perhaps these represents two Proto-Indo-European homonyms; perhaps there is a deeper philosophic connection between the words “black” and “time.”

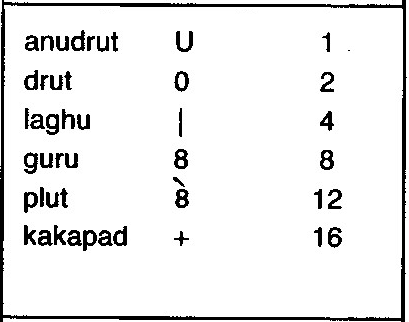

Kshan or kan is the shortest interval acknowledged. According to ancient scriptures, it is the interval required to quickly pierce one hundred lotus leaves with a needle. Kshan, lav, kasth, nimish, kala, chaturbhag are referred to as “sukshma kaal,‘ which means “micro-time,” while anudrut, drut, laghu, guru, plut, and kakapad are called “sthul kaal” which means “macro-time” (Sharma 1973). The relationship is shown in table the table below:

| 8 kshan | = 1 lav |

| 8 lav | = 1 kashth |

| 8 kashth | = 1 nimish |

| 8 nimish | = 1 kala |

| 2 kala | = 1 chaturbhag |

| 2 chaturbhag | = 1 anudrut |

| 2 anudrut | = 1 drut |

| 2 drut | = 1 laghu |

| 2 laghu | = 1 guru |

| 3 laghu | = 1 plut |

| 4 laghu | = 1 kakapad |

This system is interesting but sometimes it is hard to work with; therefore it is usually interpreted slightly differently. In the contemporary interpretation, the system is defined according to the anudrut. In this approach, the smallest practical unit is defined as the length of time it takes to utter one short syllable (akshar-kaal). The relationship of the other units then falls into place as follows:

| 1 syllable=anudrut | = 1 akshar-kaal |

| drut | = 2 akshar-kaal |

| laghu | = 4 akshar-kaal |

| guru | = 8 akshar-kaal |

| plut | = 12 akshar-kaal |

| kakapad | = 16 akshar-kaal |

2nd Aspect of Dasa Prana (Marg) – Marg(h) is defined as “a way, road, path” (Apte 1987). Within this context, it is generally interpreted as the manner of progressing from one beat to another. To some this implies an interval. To others, it implies a way of playing things between the beats. It is very difficult to make any statement concerning marg which is either relevant or conventionally accepted.

3rd Aspect of Dasa Prana (Kriya) – The term “kriya” literally means “activity”, and it refers to the act of timekeeping. In the most general terms, the movement of the conductor’s baton, or the clapping and waving of the hands to denote the tal is kriya. There are two factors: 1) does the timekeeping make sound and 2) is the process consistent with the Margi system of music.

It is appropriate for us to look at the concept of Margi and Deshi tals before continuing. This is linked to the distinction between Margi Sangeet and Deshi Sangeet. Margi Sangeet means “the music of the path”; this is music which is fit to be a mechanism for spiritual enlightenment. This is contrasted with Deshi Sangeet, which means, “music of the countryside” or “indigenous”; this is music which arises spontaneously from the people. It is music for mere sensual enjoyment and is unsuitable for spiritual growth.

The concept of Margi Sangeet is closely tied to Hindu mythology. There is a Promethean myth that says that the Gods decided to give the gift of sangeet (music) to mankind to act as a new Veda, one which would be accessible to all people (Rangacharya 1966). According to this myth, a saint by the name of Narada was chosen as the vehicle for its propagation. Therefore, the music that flowed from the gods and demigods, through Narada, to man, is Margi Sangeet.

But how does this fit in with contemporary music? If one is not too particular at looking at the facts, then it isn’t too difficult; Margi Sangeet is classical music, while the popular forms of music comprise the Deshi Sangeet. This is actually a defensible position if one wishes to confine oneself to looking at it from a standpoint of class and social structures. The ancient concepts of Deshi vs. Margi Sangeet are nothing more than a reflection of the class associations of the music of antiquity.

Unfortunately, if we look at this from the standpoint of the music, this association fails. Although classical music has existed in some form since antiquity, it is very much a “ship of Theseus”. Elements of the original music have been slowly replaced by new musical forms until today, no component of the original music survives. All of the new elements are derived from sources which clearly would be classified a Deshi.

The second consideration of kriya is whether or not it produces sound. Any form of timekeeping which makes a sound is considered to be “sashabd“. This would include clapping of the hands, stomping of the feet, beating sticks together, etc. This is opposed to forms of timekeeping which do not produce a sound; this is called “nishabd“.

So this brings us back to the concept of kriya. There are two criteria, the first being whether the timekeeping produces a sound and the second is whether it is Deshi or Margi. When we mix the two factors together we get four classes. Here are the various kriya:

Marg/ Sashabd Kriva – This is timekeeping with sound in the marg tradition. There are several classes: a) Dhruva – Snap fingers. b) Samyak – Hold right hand stationary and beat with the left hand. c) Tal – Hold left hand stationary and clap with the right. d) Sanipat– Clap by moving both hand together.

Marg / Nishabd Kriya – This is timekeeping without sounds in the marg tradition. Its classes are: a) Avapap – Count the time with the fingers of the hand turned upwards. b) Nishkram – Count the time with the fingers of the hand turned downwards c) Vikshep– Move hand to right side. d) Pravesh – Move fingers to left.

Deshi / Sashabd Kriya – Any variety of clapping or snapping of fingers in the deshi tradition.

Deshi / Nishabd Kriya – This is timekeeping without sounds in the deshi tradition. Its various classes are: a) Sarpini– Move your hand to the right. b) Krshya – Move your hand to left. c) Padmini – Throw down the hand with the palm turned upwards. d) Visarjit – Move the hand upwards with the open hand up. e) Vikshipt – To indicate time by closing the fingers. f) Patak – Raise the open hand. g) Patit – Bring the hands downward.

The preceding discussion, although clearly irrelevant to contemporary practise is nonetheless fascinating. We see that the system of clapping and waving of hands to keep the tal is of extreme antiquity. Although the particulars have ebbed and flowed with the passage of time, the general theme has been remarkably consistent.

4th Aspect of Dasa Prana (Ang) – The word “ang” literally means “limb,” or “organ.” This implies a section of the tal. Each ang is defined by the clap. The ang may be specified according to one of six durations as shown in table below:

This system has been expanded to include a number of combinant forms as shown in table below:

| Name | Duration |

| drut viram | 3 |

| laghu viram | 5 |

| laghu drut | 6 |

| laghu drut viram | 7 |

| guru viram | 9 |

| guru drut | 10 |

| guru drut viram | 11 |

| plut viram | 13 |

| plut drut | 14 |

| plut drut viram | 15 |

This system of angs has been applied to contemporary practise in an interesting manner (Sharma 1977). The division of angs in Tintal goes as follows:

1 2 3 4 – 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 – 13 14 15 16

We see that the ang is roughly comparable to the modern concept of vibhag, except that the khali is unable to define an ang, where it is able to define a vibhag. It should be brought out that the distinction between ang and vibhag may be purely academic. It appears that in past, there often was no khali as we think of it today. Therefore with such a conceptual model, one would not be able to make any distinction between vibhag and ang. It is also possible that this distinction between vibhag and ang is purely idiosyncratic of this author (Bhagavat Sharma).

There is a more fundamental problem with modern interpretations of ang. It is very clear that ang is based upon an absolute concept of time. The durations are clearly specified in terms of aksharkaal. One aksharkaal is defined as the length of time it takes to utter one syllable. Contemporary practise is based upon the matra. Matra is not defined according to any particular duration. In fast pieces the duration is short, in slow piece the duration is long. Therefore these fundamental philosophic incompatibilities make the entire concept irrelevant to contemporary practise.

5th Aspect of Dasa Prana (Graha) – Graha is the method of starting the percussion. If the percussion starts at the same time as the rest of the music, it is referred to as samagraha. If the percussion and the rest of the music start at different times, it is said to be visham. Within visham graha there are two varieties: atit and anagat. Atit is the process of starting after the sam while anagat is the process of starting before the sam. One should keep in mind that while the ancient interpretation of graha concerns the starting of the piece; contemporary interpretations concern the resolution of the piece. Therefore today, atit graha refers to a composition which ends after the sam, while anagat is a composition which ends before the sam.

This is not as much of a contradiction as it might appear. We should keep in mind that the importance here is cadential rather than structural. This is to say that today the point of emphasis comes at the end of an expression while there is evidence that in centuries past, the point of emphasis was at the beginning. Take for an example South Indian music, where it is normal to start the composition on the first beat as opposed to north Indian music where the tendency is to start at some point midway in the cycle and lead up to sam. When we view the graha from the standpoint of the cadence rather than merely a starting point, we see that it has remained surprisingly consistent over the centuries.

6th Aspect of Dasa Prana (Jati) – The word “jati” literally mean a “caste,” “collection,” or “class”. There are five jatis: tryastra (tisra), chaturstra, khand, mishra, and sankirna. Tryastra is made of three beats, chaturstra is made of four beats, khand is made of five beats, mishra is made of seven beats and sankirna is made of nine. It refers to the pulse of the piece. Therefore anything which has a strong triplet feel is tryastra, quadruple feel is chatustra, etc. This definition may be confusing because jati is sometimes be applied to the entire tal (e.g., dadra=triyastra, kaherava = chatustra, etc.) while at other times it is applied to the layakari (e.g., chaugun =chutustra, adi or tigun=triyastra etc.) Generally it is a question of “feel” rather than any theoretical structure.

The definition according to “feel” is significant. It has been mention by other authors (Vinjamuri 1986) that the jati is defined according to the lagu. Therefore it is defined in terms of absolute time, rather than relative time. The laghu appears to be approximately 1/ 80th of a minute. This is quite significant because this is an inborn rhythm. It is easily seen that a rhythm which is easiest to feel is one which is close to the human heartbeat. Although the matra may have any value, it is most perceptible when it is approximately 80 beats-per-min. Very fast or very slow must be perceived in terms of fractions or multiples in order to be easily felt. Therefore defining the jati in terms of “feel” (i.e., laghu) is a vestigial concept from an era when the theory of rhythm was based upon an absolute reference of time (i.e., anudrut, drut, laghu, etc.), rather than the present relative reference of time (i.e., matra),

7th Aspect of Dasa Prana (Kala) – This is a particularly difficult term to define. It is clear that it relates to some type of section or division, but the exact musical significance seems to be lost. According to some authors, it relates to the vibhag or measure (Vinjamuri 1986). However, such a definition impinges uncomfortably on the concept of ang. According to other authors, it is relates to the size of a structure in each matra (Sharma 1973). Therefore if musical notes were used to express it; 1 kala=SaReGaMa, 2 kala = SaSaReReGaGaMaMa, 4 kala = SaSaSaSaReReReReGaGaGaGaMaMaMaMa” etc. Unfortunately this definition impinges on the concept of jati.

Most authors simply make some inscrutable remarks and move on. Since nobody seems to have any idea as to exactly what either the ancient or contemporary significance of kala was, we too shall just move on (after leaving you with these inscrutable remarks).

8th Aspect of Dasa Prana (Laya) – This is the tempo. This concept has been explained at great length earlier.

9th aspect of Dasa Prana (Yati) – Yati has been described as the structure and arrangement of the various ang. That is to say that it is the way in which structures are put together within the composition. Although different authors have given slightly differently numbers of possible yati, the common ones are: sama, srotagata, mridanga, gopuchcha, and damaru.

10th Aspect of Dasa Prana (Prastar) – Prastar is the process of mathematical permutation. There have been numerous discussions, interpretations, and reinterpretations over the centuries. We will illustrate a common contemporary interpretation. This contemporary interpretation is very relevant to the subject of theme-and-variation as found in kaida and rela. We will start with a four beat structure. It may then be broken up and recombined in the following manner:

4, 2+2, 1+3, 3+1, 1+1+2, 1+2+1, 2+1+1, 1+1+1+1

Final comments about the Dasa Prana – We have given an extensive description of the Dasa Prana of tal; however, a few comments are in order. Although there is a tendency for many educated musicians to try and apply this to contemporary practise, there are fundamental difficulties.

The most fundamental problem is in the basic musical concept of time. It is clear that the Dasa Prana is based upon an absolute concept of time (e.g., seconds, milliseconds, etc) while the present north Indian system is based upon the relative concept of time (e.g. beats). This is indicated by the fact that the fundamental unit is the anudrut which is defined as the length of time it takes to utter one syllable (akshar kaal). There is a general tendency to equate the laghu with the matra, but they are philosophically incompatible. In contemporary practise, the matra is clearly a relative reference point while the laghu is fixed in absolute time. Since the entire system of Dasa Prana is based upon an absolute concept of time, it renders much of this system irrelevant to contemporary practise.

Conclusion

This page went into great depth about the North Indian system of rhythm. This system, known as “tal” or “tala“, has a hoary past. But it has undergone considerable change over the centuries. The cumulative effect of these changes produced a rich artistic tradition which makes North Indian rhythm different from anything else in the world. Even its twin sister, the system of “thalam” in the deep South, has notable differences.

Selected Video

Works Cited

Apte, Vasudeo Govind

1987 The Concise Sanskrit English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

Gottlieb, R. S.

1977a The Major Traditions of North Indian Tabla Drumming. Munchen, Germany: Musikverlag Emil Katzbichler.

Mani, T.A.S.

no date Sogasuga Mridanga Taalamu. Bangalore: K.C.P. Publications.

Pathak, R.C.

1976 Bhargava’s Standard Illustrated Dictionary of the Hindi Language. Varanasi: Bhargava Bhushan Press.

Patnakar, R. G.

1977 Tal Sopan (Vol. 2). Bulandshahar, India: Sangeet Kala Kendra.

Rangacharya, Adya

1966 Introduction to Bharata’s Natya-Sastra. Bombay, India: Popular Prakashan.

Sharma, Bhagavat Sharan

1973 Tal Prakash. Hathras, India: Sangeet Karyalaya.

1977 Tal Shastra. Alighar, India: B. A. Electric Press.

Shepherd, Francis Ann

1976 Tabla and the Benares Gharana. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International. Ph.D. Dissertation, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT.

Stewart, Rebecca Marie.

1974 The Tabla in Perspective. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International. (Ph.D. Dissertation UCLA).

Vinjamuri, Vara Narasimhacharya

1986 Tal Lakshanam. Kakinada, India: Padmini Printers.