Musical Notation and the Internationalisation of North Indian Music

There are several overall approaches to the internationalisation of North Indian music notation. One approach is to translate everything into staff notation. Another is to use a Bhatkhande notation, but shift the script to Roman script. A third approach is to modify a Roman script Bhatkhande notation in way to accommodate limitations in electronic media; this is based upon the use of upper and lower case letters to indicate which position the movable notes occupy. (This last approach will be discussed in a separate section dealing with electronic media.)

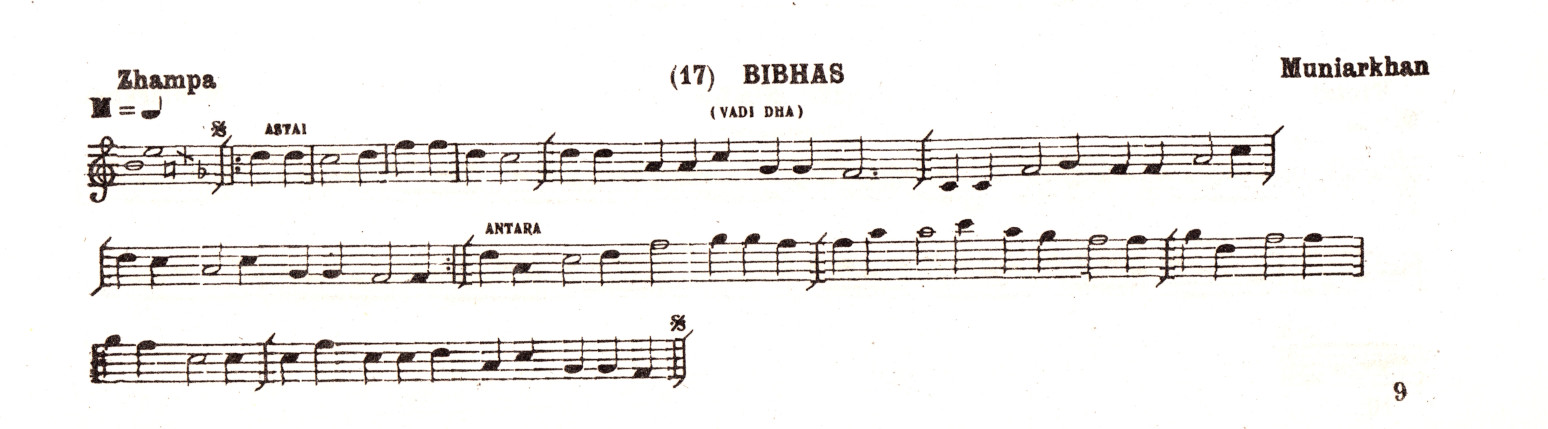

Staff notation is often used for Indian music, but it is a very controversial issue. It is true that staff notation has the widest acceptance outside of India. This is no doubt a major advantage. An example is shown below:

Unfortunately, the use of staff notation distorts the music by implying things that were never meant to be implied. When a notational system conveys wrong information, this can be just as bad as the inability to convey important information.

The biggest false implication of staff notation is the key. Western staff notation inherently ties the music to a particular key. This is something that has never been part of Indian music. In India, the key is merely a question of personal convenience. Material is routinely transposed up and down to whatever the musician finds comfortable. Over the years a convention of transposing all material to the key of C has been adopted; unfortunately, this convention is usually not understood by the casual reader. Furthermore, this convention is not always adhered to, especially by Western authors.

One other false implication is that of equal-temperament. This clearly is not implied in Indian music.

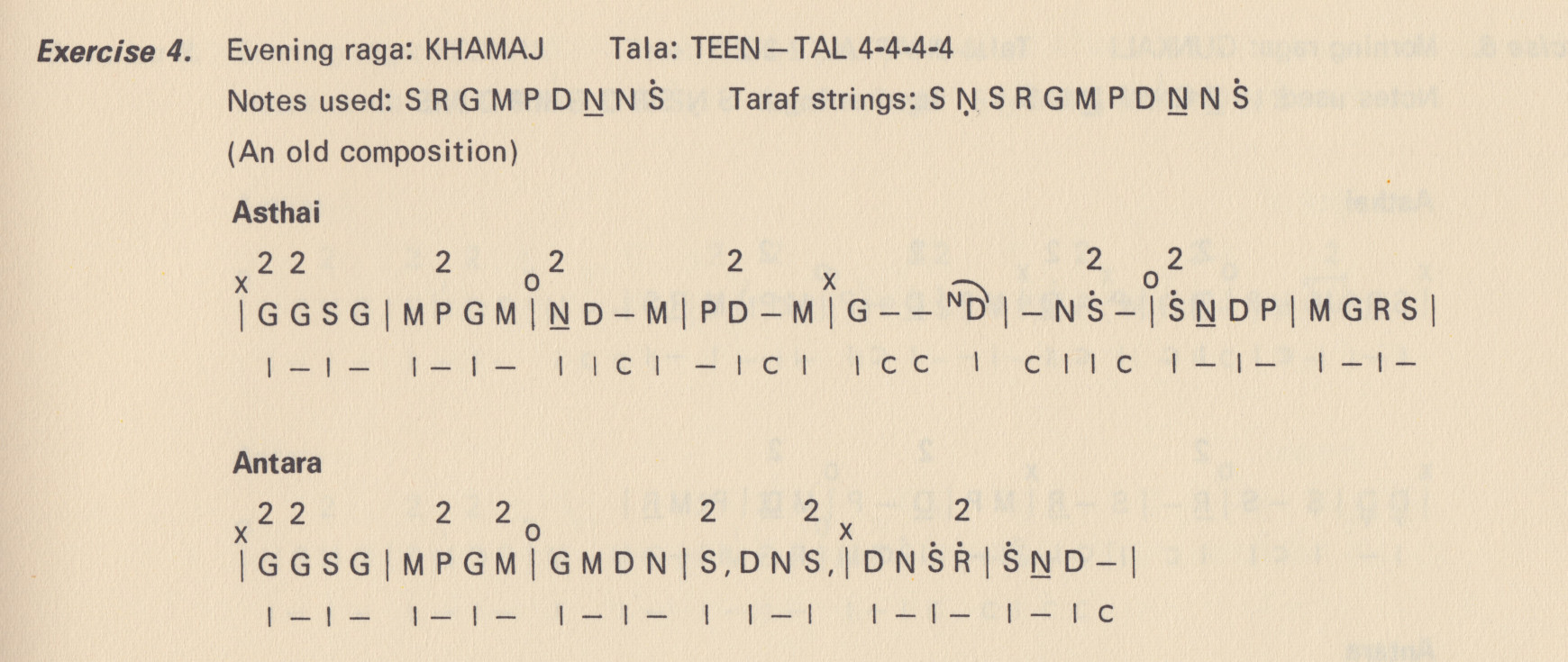

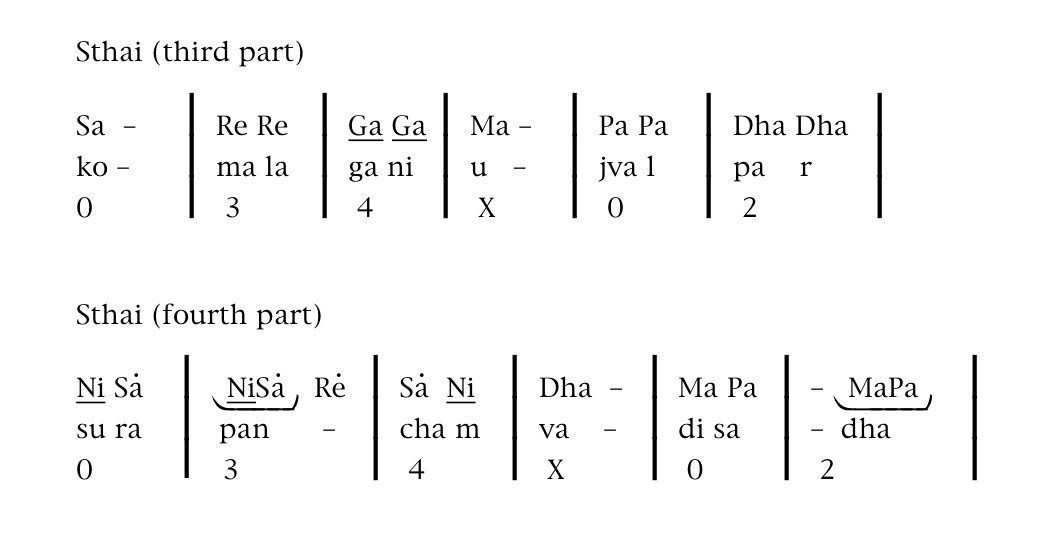

Staff notation is not the only approach to the internationalisation of North Indian music, simply writing a Bhatkhande notation in Roman script is the another approach. One example is shown below:

This is a straight-foward use of the Roman script for a standard Bhatkhande notation; but there are additional elements to specify sitar techniques. Bhatkhande’s approach does not preclude any such additions. However there is one thing which is a significant deviation. One will notice that the second and third claps of Teental are not specified, instead they are merely implied by the vibhag structure. Furthermore, the “2” has been hijacked to serve as a notational element for the sitar technique.

The biggest advantage of writing Bhatkhande notation in Roman script is that it does not distort the original material. Since Bhatkhande’s notation was never actually tied to any particular script, it is arguable that this is really no change at all. The widespread acceptance of Roman script, even in India, means that it has a wide acceptance.

However, the use of Roman script / Bhatkhande notation is not without its deficiencies. The biggest problem is that it still requires a firm understanding of the structure and theory of North Indian music. The practical realities of international book distribution and more especially the Internet, mean that information should be instantaneously accessible. One should not expect a casual visitor to a website, or a musician browsing through a music book, to invest the energy required to master the Bhatkhande notation.

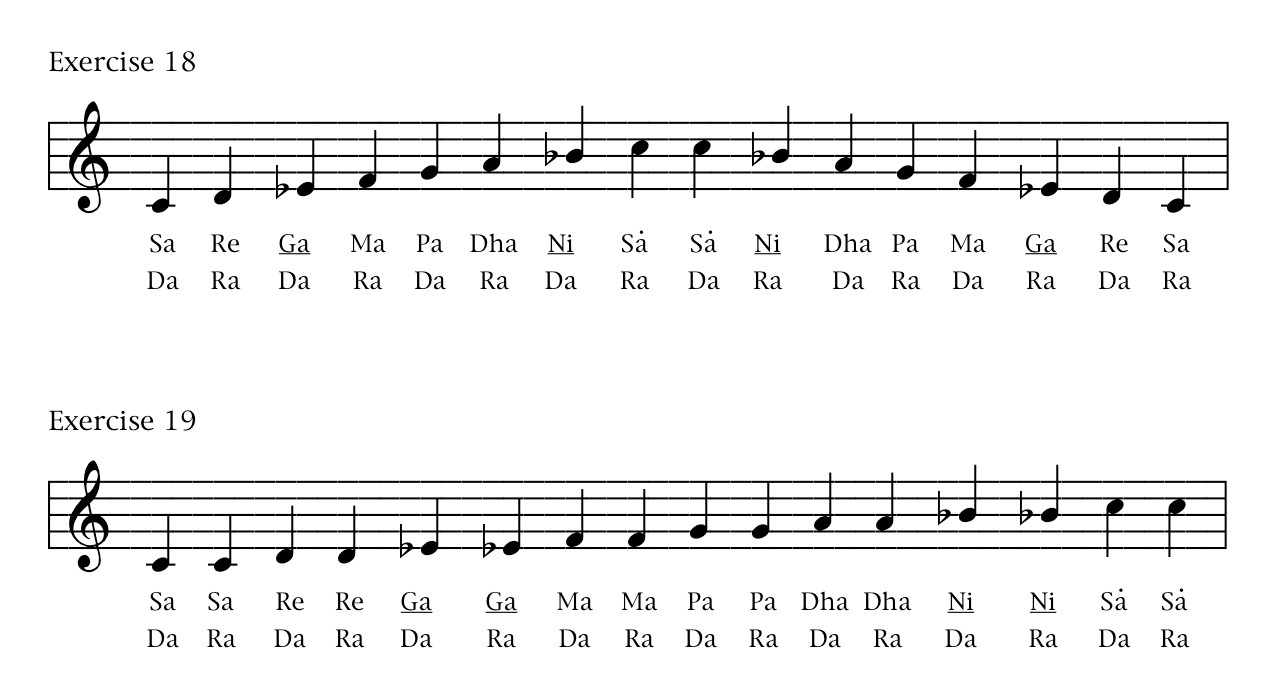

Another easy way to promote the internationalisation of North Indian music is with a combined notation. An example of some basic exercises of rag Kafi in a combined notation is shown below:

This notation has all of the clarity of Bhatkhande notation, as well as the accessibility of staff notation.

Indian Musical Notation in Braille

There are options for Indian music notation for the blind (Veer 1978).

Indian Notation and the Electronic Media

The introduction of word processors and the advent of the Internet have exerted a tremendous influence over the development of North Indian musical notation. This is because the Bhatkhande notation is not directly supported by any of the standard encoding schemes.

In the present computing environment, one is forced to make certain modifications in one’s approach. People have to choose whether to modify the software to accommodate the notation, or to modify the notation to accommodate the limitations of computers. Both approaches are in use.

Modifying the Notation – One popular approach modifies the way in which the sargam is specified. Here is portion of an example from a Wikipedia article on Rag Todi (Wikipedia 2021).

Let us make a few observations about this notational system. To begin with, it is based upon the sargam, as most Indian systems are. However it uses a different way to describe the alternative forms of notes. This is described in the table below:

| S | r | R | g | G | m | M | P | d | D | n | N | S’ |

| Sa | Komal Re | Shuddha Re | Komal Ga | Shuddha Ga | Shuddha Ma | Tivra Ma | Pa | Komal Dha | Shuddha Dha | Komal Ni | Shuddha Ni | Sa |

This notational system was adopted by the Ali Akbar College of Music in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was convenient because it allowed anyone with a typewriter to write Indian music with great precision. This college turned out numerous students who were influential in the use of the Internet for the propagation of Indian music. Consequently it is a very common approach to dealing with North Indian music on the Internet.

This form of notation had its origins in the state of the technology half a century ago. If you were banging away at a typewriter in Northern California in the pre-Internet days, there were very good reasons to use this notation.

Today, its raison d’etre is gone. There is no reason to continue using this system other than laziness or ignorance of established conventions.

Minimal Modification – It is possible to implement a standard notation with only minimal adjustments. The present Unicode standard supports an almost unthinkable number of glyphs, many can be used to approximate a standard Bhatkhande notation. The table below is more consistent with traditional notation, yet is still compatible with almost all digital platforms:

| Sa | Re | Re | Ga | Ga | Ma | Mà | Pa | Dha | Dha | Ni | Ni | Sa’ |

| Sa | Komal Re | Shuddha Re | Komal Ga | Shuddha Ga | Shuddha Ma | Tivra Ma | Pa | Komal Dha | Shuddha Dha | Komal Ni | Shuddha Ni | Sa |

Modifying the Software – It is possible to completely accommodate a standard notation by modifying the software. Although Indian musical notation is not directly supported by current environment, this can be changed.

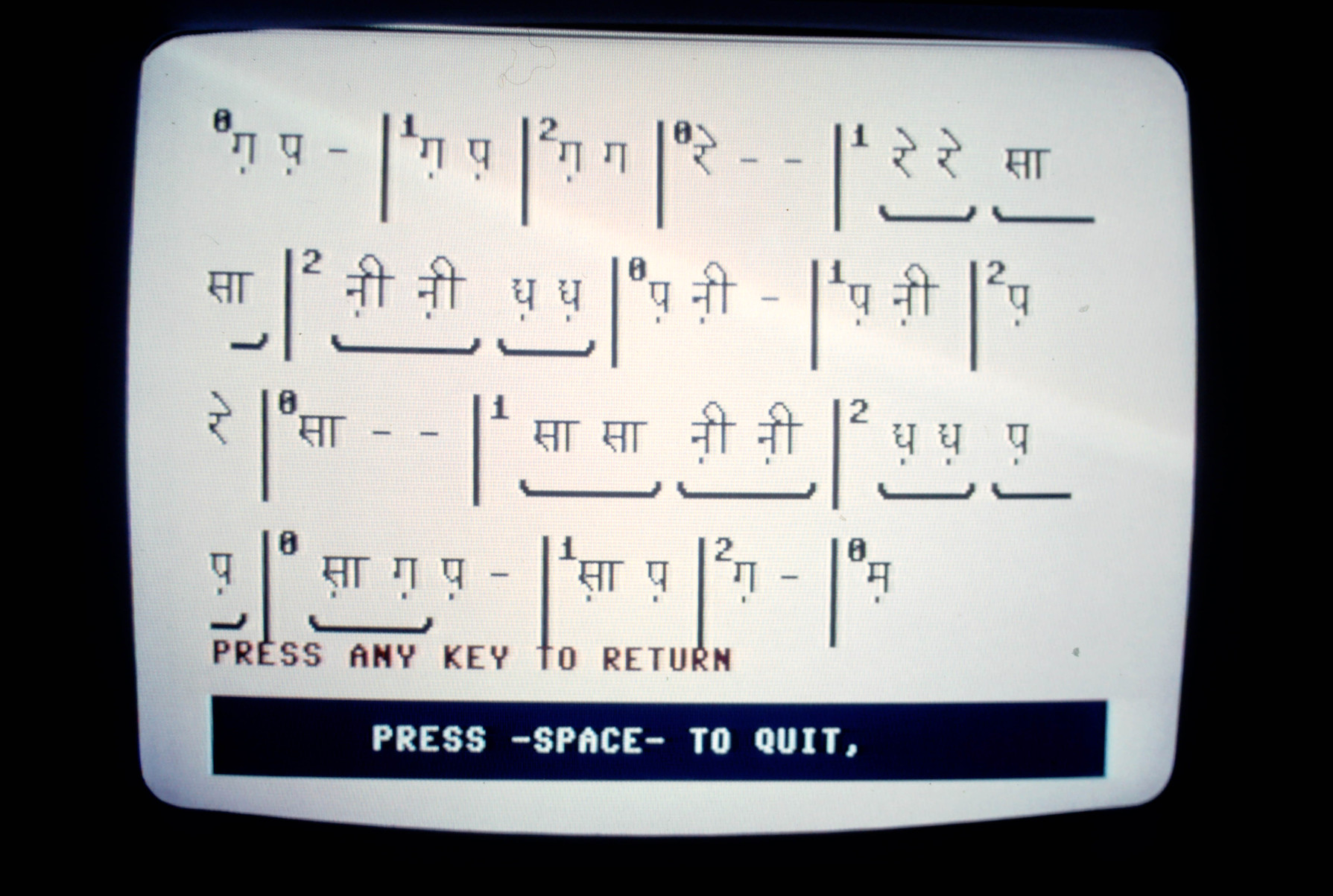

The modification of a computer’s software to support traditional Indian notation is not new. It predates the widespread use of the Internet by a number of years. One system was in use as early as 1987 (Indian Express 1987). This could handle an audio output as well as a simultaneous display of the notation in a Bhatkhande format (United News of India 1987). Below is an implementation of a Devnagri / Bhatkhande notation on a vintage 8-bit computer (Courtney 1991).

These early endeavours were far more difficult than what is required today. They required an extensive reworking of the operating system. However the modular approach of modern operating systems makes things easier. Below is a sample of text that was made with a standard word processor with no more than the alteration of a few characters in the font (Courtney 2015) :

SVG – There is another approach to the handling of North Indian musical notation; this is in SVG. SVG is an abbreviation for “Scalable Vector Graphics”. This approach is philosophically similar to the redefinition of characters in a font. However for Internet based applications, it has the advantage that it does not require the user to download a custom font set.

Unicode – The ultimate solution will undoubtedly be in the Unicode system. This is a continuously evolving system of encoding characters from around the world. The majority of the elements are already in place, but significant holes exist. Until such a day when these holes are filled, we will be forced to other means to implement a notation.

Notation Software – The ideal situation would be a complete coverage of North Indian musical notation by the Unicode standard; but until this happens there is software to handle this. The various low level hacks that we have alluded to need not be done by the casual user, because software is available from programmers who have already done this.

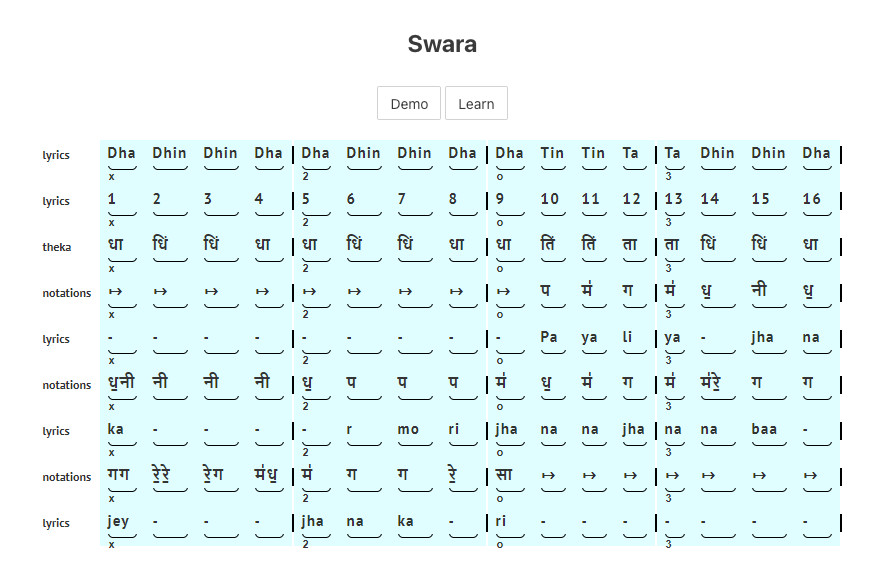

One example is “Sargam”. This is an open source software that works on both Mac as well as PC. It allows the user to type in a detailed notation of Indian music without having to do the programming themselves. It works in both Roman script as well as Devnagri. An example is shown below:

Another software package for the notation of Indian music is “Vishwamohini”. Below is a sample taken from their website:

These systems are still in the developmental stage. But they offer tremendous possibilities and hope for the future.

Conclusion

The notation of Indian music is arguably one of the longest running “work in progress” that the world has seen. Perhaps it is just in the nature of things that it will never truly be worked out. I just hope that this modest survey of the subject will inspire someone else to take it up and perhaps iron out the last few wrinkles.

Selected Video

Works Cited

Bharatamuni – Sri Satguru Publications (translators)

undated – The Natya Shastra. (Translated by a Board of Scholars), Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications.

Bhatkhande, Vishnu Narayan

1993 Hindustani Sangeet – Paddhati (Vol 1 ): Kramik Pustak Malika. Hathras: Sangeet Karyalaya.

2001 “Vasant – Trital (Madhya Lay)” Hindustani Sangeet – Paddhati (Vol 4 ): Kramik Pustak Malika. Hathras: Sangeet Karyalaya.

Blockmann, H. (translator) Abu l-Fazl Allami (author)

Circa 1590 Ain-i Akbari. Translated by H. Blockmann. Delh: 1989. Reprinted by New Taj Office.

Courtney, David R.

1991 “The Application of the C=64 to Indian Music: A Review”, Syntax. June/July: pp. 8-9: Houston.

Courtney, David R. and Chandrakantha Courtney

2015 Elementary North Indian Vocal: Vol. 1. Houston: Sur Sangeet Services.

Courtney, David R. & Srinivas Koumounduri

2016 Learning the Sitar. Pacific MO: Mel Bay Publications.

Deodhar, B.R.

1993 Pillars of Hindustani Music. Translated by Ram Deshmukh. Bombay: Popular Prakashan Pvt. Ltd.

Express News Service

1987 “Raga Recording on Computer”. Indian Express. Wed, Nov. 18, 1987. Hyderabad: Indian Express.

Garg, Balakrishna (editor)

1976 Brihaddeshi. Hathras, India: Sangeet Karyalaya.

India, Ministry of Culture and Broadcasting

2021 Brhddsi Sri Matanga. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. http://ignca.gov.in/brhaddesi-of-sri-matanga-muni/. Last updated Sept 17th, 2021. Downloaded Sept 18, 2021.

India Postal and Telegraph. Govt of India

1973 V.D. Paluskar Memorial Stamp. Govt. of India.

Khan, Sadiq Ali

1874 Sarmaye Ishrat. Delhi: Narayani Press.

Khokhar, Mahfooz

1998 Rag Swaroop. Karachi: Fareed Publishers.

Klostermaier, Klaus K.

1994 A Survey of Hinduism. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Griffith, Ralph T.H.

1896 The Hymns of the Rig Veda: Translated with a Popular Commentary. Benares: E.J. Lazarus & Co.

Patwardhan, V.N.

1947 Rag Vijnan. (Vol 4). Poona: Vinayak Narayan Patvardhan.

Puranastudy

2021- CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. (downloaded Sept. 18, 2021).

Saletore, R.N.

1985 “Vedas”, Encyclopaedia of Indian Culture (Vol. 5 V-Z), pp1562-1566. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Sastri, S. Subrahmanya, and S. Sarada (editors)

1986 Sangetratnakara of Sarangsdev (vol 3). Madras: Adyar Library and Research Centre.

Shankar, Ravi

1968 Ravi Shankar: My Music, My Life. New Delhi, India: Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd.

Sri Satguru Publications

1986 “Bibhas”. Encyclopaedia of Indian Music with Special Reference to the Ragas. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications.

United News of India

1987 “American Develops ‘Raga’ Processor”. NewsTime, Mon. Nov. 16, 1987, India: News Time India.

Veer, Ram Avatar

1978 History of Indian Music: Notation System. New Delhi: Pankaj Publications.

Welch, Sarah

2018 File:1500-1200 BCE, Vivaha sukta, Rigveda 10.85.1-8, Sanskrit, Devanagari, manuscript page.jpg. Uploaded by Sarah Welch.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1500-1200_BCE,_Vivaha_sukta,_Rigveda_10.85.1-8,_Sanskrit,_Devanagari,_manuscript_page.jpg Downloaded Sept 3, 2021.

Sargam Software

2021 https://sargamdev.wordpress.com/ Downloaded Oct 3, 2021

Vishwamohini Software

2021 http://vishwamohini.com/music/home.php, Downloaded Oct 3, 2021

Wikimedia Commons

2009 Brahmi pillar inscription in Sarnath. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d8/Brahmi_pillar_inscription_in_Sarnath.jpg. Downloaded Sept 10, 2021.

Wikipedia

2021 “Todi (Raga)”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Todi_(raga). Wikipedia. (screen capture Sept 23, 2021).